‘Jack Brought Us All Together’: After 42 Months, Community Finds Its Lost Son

For roughly 1,225 days, Kim Cantin didn’t have answers.

A mother searching for her first born.

Her 17-year-old Eagle Scout was missing amid the catastrophic Montecito Debris Flow of January 9, 2018.

Other deceased were found. But not Jack, not her kind-hearted, gentle soul of a young man.

But in late May of this year, after an exhaustive 42-month search for the Santa Barbara High student through 110 acres in Montecito, a mother finally got her closure.

Jack had been found, just 1,000 feet away from his childhood home, with household items buried around him aiding in the process.

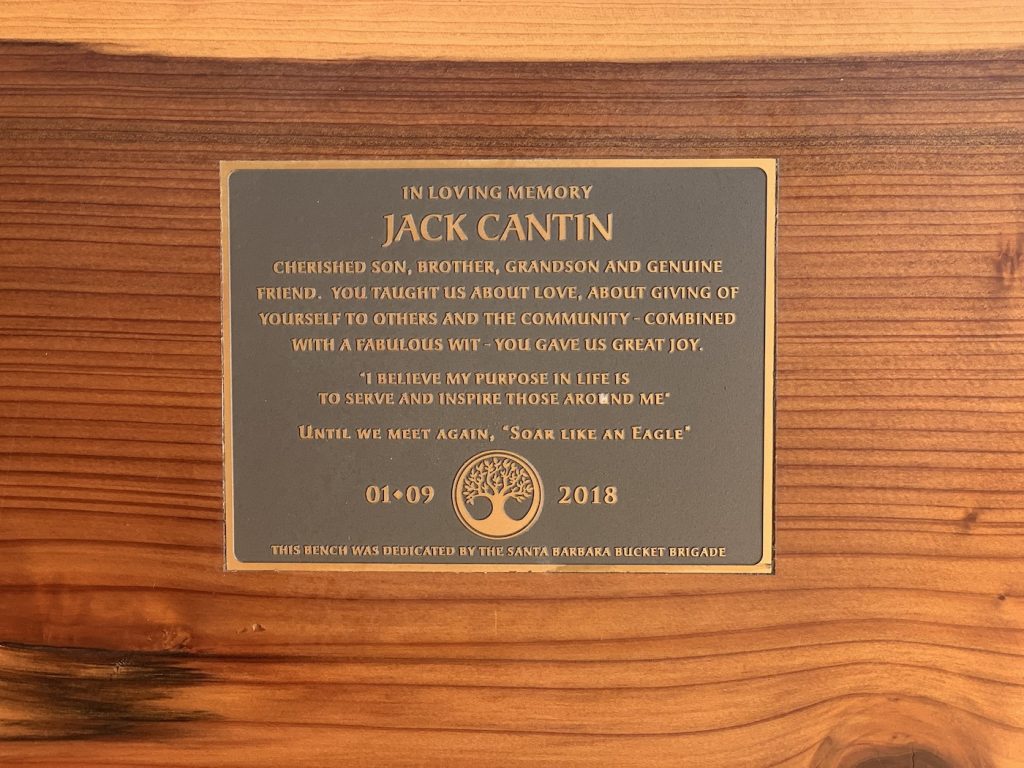

“All the hope. All the prayers. The determination, it helped us find a needle in the haystack,” Kim said while sitting on a bench dedicated to Jack at Upper Manning Park’s Scout House.

Her Jack, a proud Montecito Union School and Santa Barbara Junior High alum, can now physically be buried next to his father, Dave, who also passed that tragic night.

“They can finally be together,” Kim said. “He’s home.”

Much like Jack’s humble attitude and caring nature, Kim is hesitant to take the spotlight or credit, instead gushing about volunteers that helped her navigate creek beds; local contractors that used their own equipment to aid in the search; local law enforcement and firefighters that laid the ground work; specialty canines that came in from San Francisco to aid; and to Danielle Kurin, the assistant professor at UCSB’s Department of Anthropology, who ultimately gave Kim the hope to carry on with the search when she was ready to accept a sobering reality in late 2019.

This recovery wasn’t just important for Kim and the Cantin family — it was critical for the community.

“I’d get tips from random strangers about a vision they had, and we’d go check it out,” Kim said. “Even if it didn’t pan out, it was a place we didn’t have to go back to. This community lifted us up in so many ways.

“Jack brought us all together.”

‘They are as good as it gets’

With both Kim and her daughter, Lauren, initially dealing with major injuries — the latter becoming a ray of hope when she was rescued after hours submerged in the debris — the physical search for Jack had to be community based.

And help came in all forms, including Grant Dyruff, a longtime friend of both Dave and Jack through the work that they both had done with Troop 33, a Boy Scouts group resurrected under Dave’s guidance.

“We felt we owed both of them,” Dyruff said. “After all they had done for the entire troop, we wanted to give back however we could.”

Dyruff hadn’t spoken more than 50 words to Kim over the years. But that didn’t matter.

Dyruff would become an outlet for the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Department, with bags of the Cantins’ household items delivered to him. He’d spend hours drying paperwork, photos, anything that came in the bags.

Most of it would be jettisoned by Kim, but there were gems that Dyruff would come across.

That included sheets of Jack’s schoolwork — “one A after another A after another A,” Dyruff said — and plenty of photos that showcased the tight-knit nature of the Cantin family.

And that family dynamic aided in seeing Jack’s star rising quickly, as the teenager co-founded Teens on the Scene at SBHS, a community service group that did city cleanups and aided the homeless.

“I took a lot of pride in rescuing as much as I could, just in case it was a memory worth keeping,” Dyruff said. “You get to know a family as you are going through very personal things — and they are as good as it gets.”

In many ways, Kim was the director of the search, her ability to brush aside heartache to keep the focus on Jack was paramount — while her sense of humor created a Pied Piper effect, with everyone willing to follow in her footsteps.

“I would have dealt with it with anger, but she managed to find the hope and humor in it all,” Dyruff said. “How can you not follow a person like that?”

Kim still finds levity when reflecting on what her SUV’s trunk looked like most days for the past three years — a shovel and boots were commonplace. She remembers being at the store and being asked if she was burying something.

“Quite the opposite,” Kim quipped.

The wear and tear of the journey did begin to weigh heavily on Kim just before Thanksgiving in 2019, where she made a deal with herself: Either progress is made by the end of the holiday, or “I’m going to let go.”

It was around this time that a pair of conversations would change the course of the investigation forever — and bring Jack home.

“Little did I know, the help we needed was just 15 minutes down the road,” Kim said.

‘If Jack were here, he’d be leading this team’

As Kim was coming to grips with potentially letting “God’s will” take over, she was discussing the case with a detective friend, going over every step that she, the volunteer rescue teams, and countless others had done to try and find Jack.

“You need a forensic anthropologist,” he would tell her.

“I didn’t even know that they existed,” Kim admitted.

Soon, a note was being sent off to Dr. Danielle Kurin at UCSB, a last-ditch effort to see if new eyes and ideas could spark the search.

Kim received a prompt reply.

“I can be in your living room as soon as tomorrow,” said Kurin, a forensic anthropologist that has worked in international disaster areas such as Peru.

Kim was in awe of what she would now have at her fingertips as Kurin readily took on the task of helping the community, and herself, find closure. Kurin was just the latest expert from UCSB to volunteer to help Montecito heal from its January 2018 debris flow. She was following in the footsteps of massive contributions to debris flow science from UCSB’s hydrology, geology, and earth sciences departments.

Already having spent thousands to bring in technology and machinery from as far as Canada, Kim was stunned that similar equipment was sitting at UCSB the entire time.

The Cantins would also inherit an army of volunteers — mostly UCSB undergraduates — willing to spend countless hours researching, testing, monitoring, and innovating amid the Montecito terrain that is still very much in the midst of its healing process.

“I had students driving every day from Los Angeles to come and dig in the hot sun for eight hours and then drive home to Los Angeles,” Kurin said. “They put thousands of miles on their cars. Why? Because Jack was their age. They saw Kim, and they saw hope and resilience. They were inspired.

“One student told me, ‘If Jack were here, he’d be leading this team.’”

Kurin found an ideal mix of tenacity and science, with the former coming in the form of thousands upon thousands of manpower hours, the latter by utilizing lasers, soil tests, and habitat recreation in order to find the tiniest of clues.

The laser — or X-ray fluorescence — has the ability to break down the composition of anything it is pointed at, with Kurin explaining that if you pointed it at a chocolate chip cookie, it gives you a rundown of the ingredients. This proved fruitful as her team tested soil, allowing them to scale down the 110-plus acres into smaller pockets of higher interest.

The team also buried pig heads to see how the remains would decay and what could be found in the soil chemistry, a process that could also be utilized on human remains, again limiting the footprint of the search.

At every turn, the group of anthropologists were buoyed by small discoveries, with materials being found that could only be the product of a post-debris flow world.

For Kurin, it was even more than that, as taking on a second full-time job became personal.

“What really struck me is that when a mother cries,” Kurin said. “That sound is the same in any language. I’ve worked with families who have had family members disappear.

“The idea of not knowing harms the human soul. And so, what we all wanted to do was to provide as much certainty as we could. For Kim. For this community.”

In just 18 months, Kurin and her crew succeeded in their quest, even if the initial communication of good news felt like any other day, with Kurin texting Kim, asking if she wanted an update on the day’s progress.

As Kim cooked one of Lauren’s favorite meals — a dish featuring chicken, artichokes, and chickpeas — she connected with Kurin.

“Kim, we found a bone,” Kim remembers Kurin telling her. “And we think it’s Jack.”

Kim almost didn’t know how to react.

“It was relief. It was almost disbelief,” Kim said. “I had been looking for so long. It almost felt like a huge weight had been lifted off my shoulders.”

Yet, she couldn’t tell the world, as the bones still needed to be tested, a 45-day process that left Kim tight-lipped.

In that time, she also reflected on how proud she was of Jack, who somehow was still impacting the world, with both Kim and Kurin believing that the learnings from this search can be applied to other disasters around the world.

“What a legacy for Jack, to have pushed us to think about things differently,” Kim said.

Yet, his final act was seemingly for his mom.

At the site where Jack’s body was recovered, the surface area was tinged with arsenic, lead, and rusty iron — none of which are conducive to flourishing plant life.

But this particular spot was overtaken by Jack’s soul, manifested in a beautiful set of flowers.

“It was Jack’s remains that allowed them to grow,” Kurin said. “It was the perfect gift for his mother.

“A lasting memory that will allow her to heal.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.