Splendor in the Gras? Norman Kolpas Eats His Way Through Foie Gras’ history, delectability, and controversy

There are few ingredients in gastronomy that have become the object of widespread controversy and debate in recent history quite like foie gras. Beloved by many chefs and gourmets for its rich flavor and smooth texture, foie gras is made from the fattened livers of geese or ducks, with the fattening typically achieved by gavage, the French term for force-feeding the birds a fatty corn-based mixture (through a tube) that engorges their liver up to 10 times its normal size.

Some call that tradition, others animal cruelty. Foie gras production has been banned in several nations, and attempts have been made to do so in several states and municipalities in the U.S., notably California, where a ban on production and in-state sales went into effect — intermittently, due to court challenges — since 2012.

In Foie Gras: A Global History, published in April 2021 by Reaktion Books Ltd. as part of its Edible series, cookbook author Norman Kolpas strives to provide a balanced account of this debated pâté’s history and production from ancient Egypt to modern times. Kolpas also explores how foie gras has inspired famous writers, artists, and musicians, including Homer, Herman Melville, Isaac Asimov, Claude Monet, and Gioachino Antonio Rossini.

The book includes a guide to purchasing, preparing, and serving foie gras, as well as recipes, from classic dishes to contemporary treats. The Montecito Journal recently caught up with Kolpas to discuss the ongoing debate of this gourmet ingredient, and the inspiration behind its classic simplicity and novel creations.

Q. Why a book about foie gras? What motivated you to dive into the debate over that particular menu item?

A. Over the years, I’ve written more than 40 books, and many of them have been about food. The history of what people eat and why and how they prepare, serve, and share it has always fascinated me. I knew a little about foie gras before starting and was fascinated by its rich history as well as by the ethical issues surrounding it, something I wanted to treat fairly and equitably in this book, not at all shying away from it.

Are there any foie gras producers who have achieved a successful ethical balance with foie gras production?

There are foie gras producers who treat their birds humanely. Hudson Valley Foie Gras, in upstate New York, observes ethical practices and even invites journalists to tour their farm and witness the process start to finish, which I did. They invited a trusted colleague of the renowned animal scientist Temple Grandin to visit and inspect their farm, and in her report, she found no fault with their force-feeding process. Other companies also follow ethical practices, including La Belle Farm, also in upstate New York; and D’Artagnan, based in New Jersey.

It’s also worth mentioning that Eduardo Sousa has been producing what he calls “ natural” foie gras at his Patería de Sousa duck farm in western Spain’s Extremadura region, which has brought him great acclaim, including a glowing report on NPR and a hugely popular TED Talk by notable New York chef Dan Barber, entitled “A foie gras parable,” that as of today (June 24) has been viewed 1,576,653 times! Sousa lets wild geese roam free on his farm, fattening themselves. Of course, that sort of approach can lead to an inconsistent supply. But, as Dan Barberexplained to me when I interviewed him, “the point of his natural foie gras is the inconsistency. He never promised he could produce natural foie gras every year.”

Regardless, in the end, concerns about foie gras should be viewed in light of other, broader issues involving animal rights and cruelty in the food industry. The eggs and chickens so many of us eat, the tender young veal so prized in some fine-dining restaurants, the factory-farmed fish that spend their short lives in overcrowded tanks and swimming in their own waste: All of these foods come about through far crueler practices than ethically produced foie gras.

According to your book, foie gras has been on the menu since the beginning of human civilization. How has it evolved into the delicacy we know today?

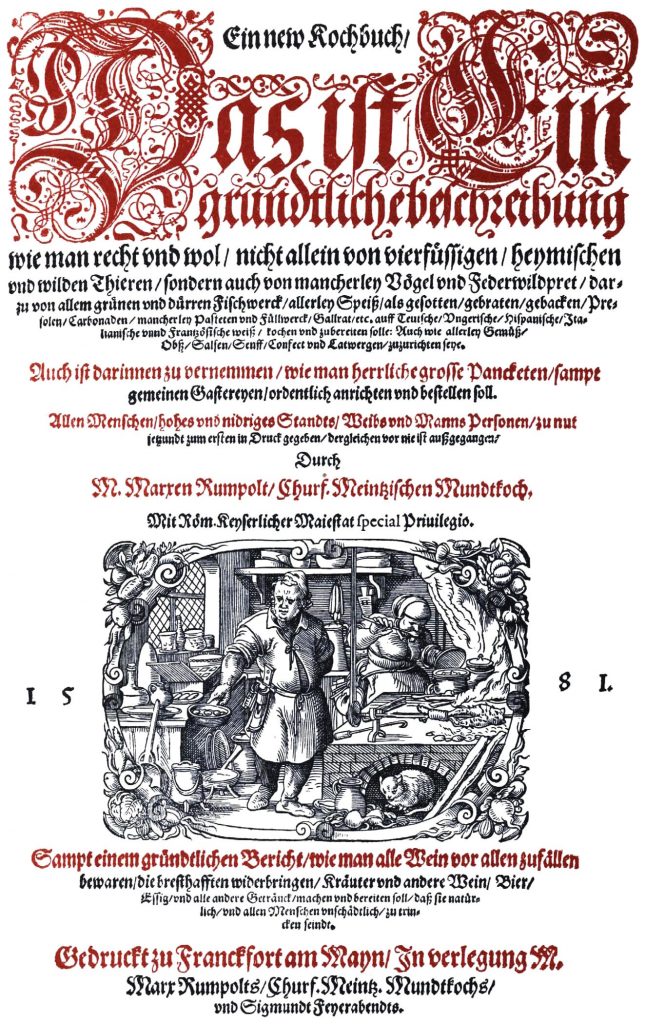

Egyptians at least four and a half millennia ago observed birds gorging on grain before migration and discovered that as a result their livers were oversized and deliciously rich, smooth, and creamy tasting. It spread from there to ancient Rome and throughout its empire. Jewish farmers, butchers, and cooks through the Middle Ages prized foie gras, not least because it provided a rich form of buttery fat that complied with kosher dietary laws. It was prized in the Vatican, too, where in the 16th century Bartolomeo Scappi, the chef to Pope Pius V, recorded a recipe for soaking the livers in milk, dusting them with flour, frying them in lard, and glazing them with Seville orange juice and sugar.

French and German chefs began preparing mousses and layered terrines of foie gras. And the ingredient reached a classic French apotheosis in the great chef Auguste Escoffier’s A Guide to Modern Cookery, first published in 1907, which included 85 different ways to prepare and serve foie gras. French chefs and central European cooks alike brought a passion for foie gras to America, where in 1889 it even appeared on the menu of the inaugural ball for President Benjamin Harrison.

Foie gras is used as an expression of passion in literature. What were some of your favorite reads?

English literature major that I was back in my college days, I was delighted to find that foie gras kept popping up as a point of reference for writers, who found it a particularly apt way to express a sense of the good life, a sensual life — or sometimes, by contrast, a life lived to excess. I love the scene in W. Somerset Maugham’s 1944 novel, The Razor’s Edge, for example, in which Isabel Bradley discusses with her uncle, Elliott Templeton, the stuffed eggs and chicken sandwiches she’s planning for a picnic lunch with her fiancé. “Nonsense,” says her uncle. “You can’t have a picnic without pâté de foie gras.”

Even contemporary, experimental, and issues-oriented fiction can deploy foie gras to make a point powerfully. In his 241-word “microstory” called Fat Liver, for example, African American writer John Edgar Wideman deplores income disparity’s impact on the food deserts of Black neighborhoods, and how our own guzzling of gasoline in our cars and information from our smartphones is a sort of electronic gavage. In that context, his unnamed character concludes, “Who gives a crap if it becomes a crime to force-feed duck or geese?”

When describing foie gras in contemporary cuisine, how does the 1960s-era nouvelle cuisine compare to today’s molecular gastronomy foie gras applications?

Since foie gras has been exalted for centuries now, it’s not surprising that each new culinary movement wants to give the ingredient its own spin. I think of nouvelle cuisine as a movement that simplified and focused the tastes of fresh seasonal ingredients. (Those same principles, when applied to the bounty of ingredients produced here in California, led to the creation of what is known as California cuisine.) I like to think of a foie gras terrine I enjoyed on a trip I made a few years ago to Bordeaux as a perfect example of that kind of simple nouvelle focus, in which a foie gras terrine — the whole livers cooked together packed into a rectangular porcelain dish, sealed with a layer of aspic, and then chilled and sliced — was presented in all its beautiful simplicity, accompanied by toasted rustic bread and a tart quince paste, both of them providing simply eloquent contrasts of taste and texture to the smooth, rich liver.

By contrast, molecular gastronomy of the soaringly creative sort practiced by chefs like the great Grant Achatz at his acclaimed Alinea in Chicago, go for surprising combinations, preparations, and presentations that bring a sort of ingenious laboratory science aspect to the ingredient. One great example is Achatz’s so-called foie gras “shooter” — not a quickly downed cocktail, as that name might imply, but instead a test tube containing layers of foie gras mousse, fig, coffee, and tarragon, all meant to be consumed in a focused explosion of flavors and textures.

The same applies to so-called “fusion” cuisine, in which the cooking traditions and styles of different countries, often from different continents, are combined. You can now find slices of the seared liver poised atop oblongs of rice to make so-called foie gras sushi, for example.

You interviewed and enjoyed foie gras cooked by some notable chefs for your book. What are examples of some of the creative preparations?

It never ceases to amaze me how ingenious and at the same time classically disciplined America’s chefs can be when it comes to preparing foie gras. During a visit I made to Lubbock, Texas, for example, young chef Cameron West at his restaurant called The West Table prepared a dish especially for me in which he accompanied neat slices of foie gras Torchon — a poached and chilled cylinder of foie gras — with the traditional Texan and Southern cornmeal fritters called hush puppies and a jam made from local peaches. I broke open a hot hush puppy, topped it with a smear of foie gras, added a dollop of the jam, and experienced a combination that seemed at once classic, contemporary, and true to the region.

What are some unexpected ways this delicacy has made its way onto menus?

At the legendary Chicago Hot Dog stand called Hot Doug’s, owner Doug Sohn offered a foie gras-topped gourmet frankfurter on a bun; and though that stand no longer exists, it was immortalized (with Sohn’s permission) in a foie-topped offering called “The Hot Doug” at another Chicago stand, The Dog House. The great French chef Daniel Boulud served a foie gras-stuffed “db Burger” at his db Bistro Moderne in Manhattan and offered a similar creation at his Bar Boulud in London.

You even see foie gras finding its way into desserts from time to time, adding an element of richness along with a not-unpleasant meaty undertone that makes sense when you think of how bacon now is sometimes included in sweet dishes as well. I was particularly impressed by “Foietella,” a commercially sold product created by chef David Briggs, owner of Xocolatl de David in Portland, Oregon, who combined foie gras with chocolate to create a gourmet product akin to Nutella. (The Seattle novelty company Archie McPhee even sold for a time a “Gourmet Foie Gras Bubble Gum” beautifully packaged in an antique-looking tin — though the product did not actually contain any foie gras.)

And you can’t talk about sweet foie gras treats without mentioning the foie gras flavor produced by Jake Godby and his business partner Sean Vahey in their San Francisco gourmet ice cream shops called Humphry Slocombe. They sometimes make it into ice cream sandwiches with big gingersnap cookies or include sweet cherries in the mixture. He got a lot of publicity for the concoction, along with anonymous death threats from animal rights activists.

Governments around the globe have taken steps to remove foie gras from menus in recent years. New York City is home to about 1,000 restaurants that serve foie gras, but in 2019, the City Council voted to ban the dish beginning in 2022. In California, which, according to The Robb Report, previously represented 20% of national foie gras sales, it’s illegal to sell it at gourmet shops and feature it on restaurant menus. Are these the final days of foie gras?

Foie gras has been legislated against here and there around the world, even at the same time that its availability and popularity have been growing. And laws are always changing. For example, the intelligent and well-written book The Foie Gras Wars, by Chicago Tribune journalist Mark Caro, details how foie gras first came to be banned in the city of Chicago, and then how that ban was overturned. And there was lots of press about how foie gras came to be banned in California, and how in 2017 the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear the case to overturn it. Yet, surprisingly, there’s been less publicity about the fact that last year a federal court reinterpreted the state law, clarifying that only foie gras production and sale were banned within the state — meaning that Californians can still purchase foie gras from out of state, just so long as they don’t then sell it here.

I would not for a moment wish to belittle the earnestness of animal rights activists, especially those who also draw attention to cruel practices in the mass production of animal-derived foods almost all of us eat every day. And those producers of foie gras who are carelessly cruel to the animals they raise deserve to be put out of business. But I don’t think ethically produced foie gras is going to disappear anytime soon.

Recipe Foie Gras with Buttermilk Cornmeal Cakes and Spiced Peach Jam

Serves 4 to 6

The combination of foie gras, house-made peach preserves and freshly deep-fried hush puppies (Southern-style balls of cornmeal batter) served by chef Cameron West at the West Table in Lubbock, Texas, inspired this easy home recipe for a cocktail party or dinner hors d’oeuvre that captures the same flavors, textures, and temperatures. Guests can eat the foie-and-jam-topped corn cakes with a knife and fork or, more informally, pick them up and enjoy them by hand.

Ingredients

1 cup good-quality store-bought peach jam

½ to 1 tsp bottled hot sauce such as Tabasco sauce

1½ cups plain (all-purpose) flour

3/4 cup stone-ground cornmeal

¼ cup sugar

2 tsp baking powde

½ tsp sea salt

¾ cup buttermilk, plus a little more if needed

1 large egg

4 tbsp unsalted butter, melted

non-stick cooking spray

9 oz foie gras Torchon, foie gras mousse or pâté de foie gras

Assemble

In a small mixing bowl, stir together the peach jam and hot sauce to taste. Set aside.

To make the cornmeal cake batter, in a mixing bowl, stir together the flour, cornmeal, sugar, baking powder, and sea salt. In a separate bowl, combine the buttermilk and egg, and whisk until combined. Whisking continuously, drizzle the melted butter into the wet ingredients. Then pour the wet ingredients into the dry ingredients and stir just until a smooth batter forms, adding a little more buttermilk if needed to achieve a thick but very slightly fluid consistency.

Having preheated a large non-stick griddle or heavy frying pan over medium-high heat, spray the hot griddle or pan with non-stick cooking spray. Using a 60-ml (1/4-cup) measuring cup, portion out the batter onto the hot griddle. Cook until the cornmeal cakes are golden brown, about 2 minutes per side, turning once with a spatula. When done, transfer to a warmed platter and continue until all the batter has been used.

Cut the Torchon into thin discs and arrange on a separate serving dish. Transfer the spiced jam to a small serving bowl. Pass the hot cornmeal cakes, inviting guests to top them with foie gras and a dollop of jam.

How To Get Foie Gras In California

Foie gras can be purchased from the state of California but it must ship from another state or country. Whenever purchasing poultry, beef and seafood from a vendor, be sure to do your research to learn more about its production. Here is a list of producers and online stores where you can get foie gras legally.

– Based in New York’s Catskills Mountains, Hudson Valley has supplied foie gras aficionados, restaurants, and caterers throughout the U.S. since 1982. On its website, you will find foie gras in all its forms: mousse, terrine, in raw slices to sear, the whole foie to cook yourself, and a delicious Foie Gras au Torchon. www.hudsonvalleyfoiegras.com

– Goudy’s French Cuisine offers foie gras crème brûlée, macaron with foie gras mousse, and foie gras chocolatine (croissant). At press time these items were out of stock. www.goudycharcuterie.com

– Based in Reno, Laurel Pine’s website claims it offers more foie gras choices than you will find anywhere else online. www.enjoyfoiegras.com

You must be logged in to post a comment.