Marguerite Ravenscroft

Her friends remembered her as eccentric, fun-loving, and generous and called her Peggy. In the late Elane Griscom’s 1990 Montecito Magazine article about Marguerite Ravenscroft, Kit McMahon, then archivist of the Montecito Association History Committee, remembered that Peggy once gave a $50,000 loan to a friend from cash tucked away in various spots in her house. Nevertheless, McMahon had noted, Peggy was a penny pincher and loved bargains, using green stamps to buy inexpensive gifts for her friends. Despite her luxurious house in Montecito, she saved money by doing her own chores. She would then estimate the difference between hiring the work out and place that amount in a glass jar to contribute to animal welfare causes. Remembered fondly by her friends, Marguerite Doe Rogers Courtney Ravenscroft, once dubbed “the millionaire society girl,” was a fascinating and complex woman of her time.

Born in San Francisco in 1890 to lumber magnate and financier John Sanborn Doe and Eleanor H. Doe, Marguerite Doe was destined to live a somewhat vagabond life. At the time of her birth, her wealthy father was 78 years old and her mother was 44. He died four years later, and his will stipulated that the bulk of his estate be held in trust for her.

A year after her husband’s death, Eleanor took Marguerite to Europe to live for a year, the first of many sojourns abroad. For the next several years, they divided their time between living in Europe and in San Francisco. Then in February 1900, The San Francisco Call made a surprising announcement – Eleanor Doe had married James B. Stetson, president of the San Francisco and North Pacific Railroad and the California Street Cable Car Company as well as a member of the firm of Holbrook, Merrill & Stetson. Unfortunately, it was not to last.

On April 18, 1906, a 7.9-magnitute earthquake struck the city and sparked an inferno that devoured whole sections of the town. Two months later, Stetson wrote a memoir of the events from his personal experience, and interestingly enough, neither Eleanor nor Marguerite was mentioned. In fact, possibly even before the quake, Eleanor had taken her 16-year-old daughter to a school in Geneva, Switzerland; whether to escape the consequences of the quake or the inferno of a bad marriage is unknown.

In 1907, Eleanor sued Stetson for divorce, claiming cruelty and violent flashes of ill temper on his part and the social snubs of his daughters. She made no claim on his fortune but wanted to resume her previous name of Doe. And so, a new chapter in the life of mother and child began.

Finishing School Graduate

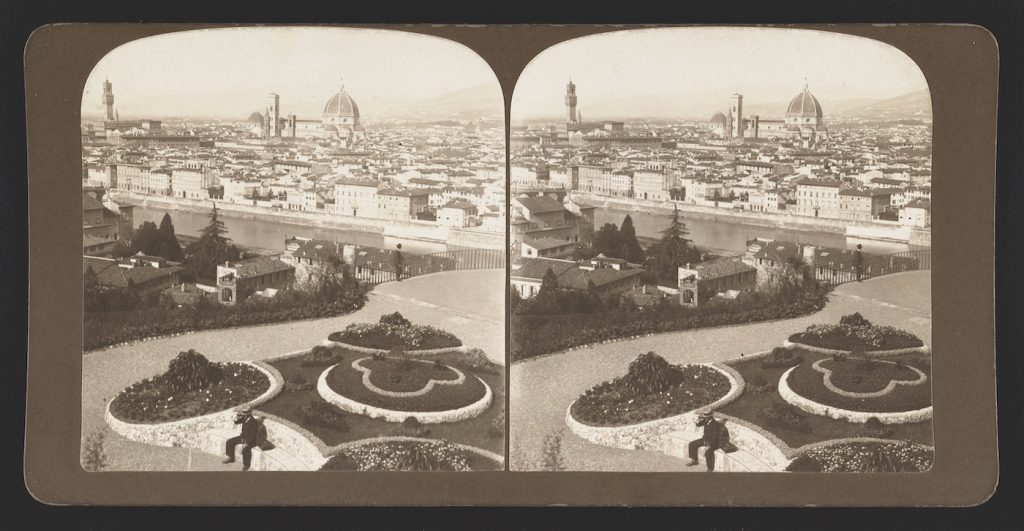

In May of 1908, Eleanor and Marguerite sailed from New York to deliver Marguerite to Miss Nixon’s School in Florence, Italy. The school was mainly for American girls and aimed at making them familiar with the great sights of Italy while instilling in them the manners and customs of high society. Miss Mary S. Nixon’s school was housed in a towered ivy-clad villa that she leased on the Via Barbacana, a narrow street that rose steeply from the square of the village of San Gervasio.

In a biography of her grandmother, the noted artist Margarett Sargent, who had attended the school two years after Marguerite, Honor Moore describes tidbits of school life that Peggy must also have experienced. The girls of the school, for instance, often took the tram down the hill for pastries at a local bakery.

A chaperone always accompanied the girls on outings to protect them from the titled but penniless young Florentine men who loitered on the Via de’ Tornabuoni on the lookout for a rich American wife. Miss Nixon, however, did host approved American, English, and Italian men at her thés dansant (tea dances) so the girls could practice their social skills.

By December 1909, Marguerite, now properly versed in the etiquette of society, had returned to San Francisco and was putting her schooling to good use by entertaining at a series of informal parties. She and her mother stayed at the Fairmont Hotel where she presided over a dinner given for her friend, Lurline Matson. In attendance were Earle Miller and Santa Barbara’s own Harold Chase, who would later develop Hope Ranch and was brother to the inimitable civic leader Pearl Chase, whose influence on Santa Barbara is still much in evidence.

Later that month, Marguerite and her mother joined Mrs. Harriet Miller and her son Earle at their home on Channel Drive in Montecito. Clearly liking the American Riviera, they leased Earlton starting in March 1910. A flurry of social events ensued. Chaperoned by Mrs. Harris Laning, wife of then-Captain Laning (he would retire as a four-star admiral of the U.S. Navy), she was a dinner guest on board the Naval cruiser USS California. She also hosted a dinner for seven friends at Earlton Lodge. Among them was Eliot Rogers, the son of Robert Cameron Rogers, poet and editor of The Morning Press, and Beatrice Fernald Rogers, daughter of pioneer Judge Charles Fernald.

Dances at the Potter Hotel, an endless stream of house guests, a chaperoned overnight trip to Cold Spring Inn (which included Eliot Rogers), and a role in Kirmess – a fundraiser for Neighborhood House – rounded off her social engagements for the season.

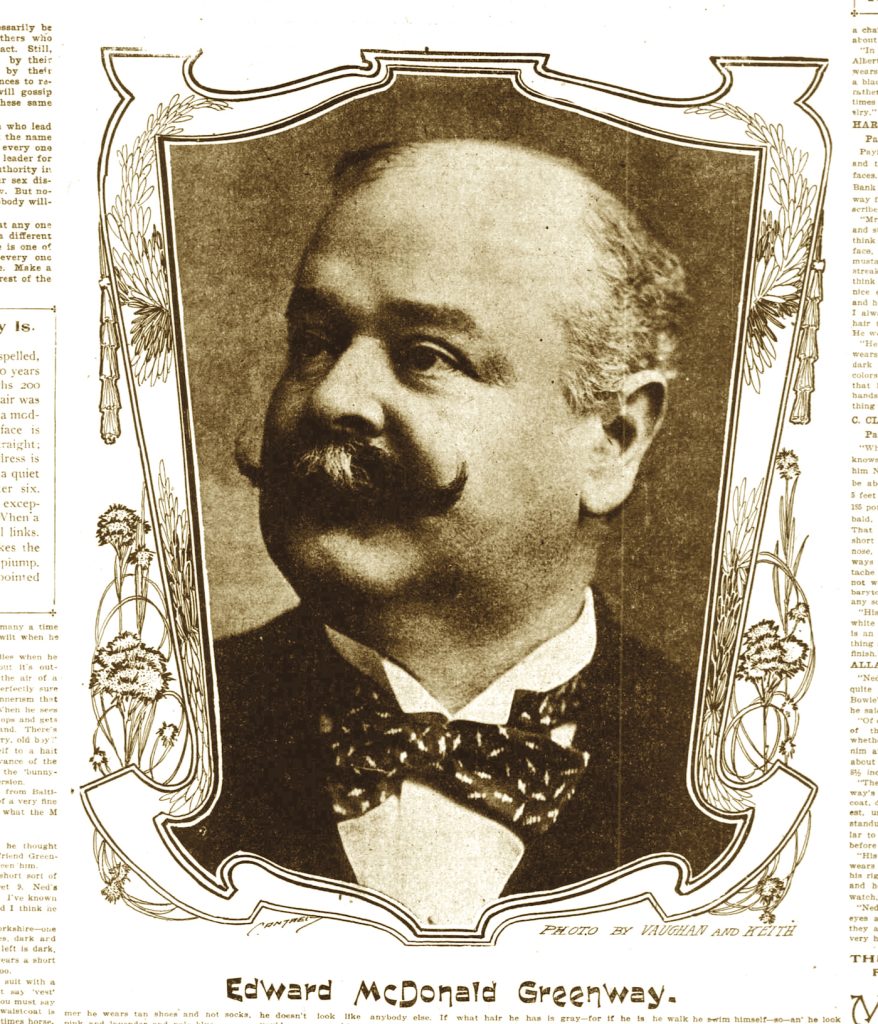

The question, of course, becomes why did she spend most of her debutante year in Santa Barbara? An answer might lie in the stranglehold that Ned Greenway and Eleanor Martin held on San Francisco society. Champagne salesman turned social arbiter, Greenway had come to the rough and tumble town of San Francisco in the 1870s, when new money scratched from the earth mingled with old money from the East Coast. By teaming up with society matron Mrs. Eleanor Martin, he was able to establish a Western “List of 400,” à la Caroline Astor in New York.

Acceptance to the list became a must in both business and society. Any breach of the strict rules of taste and manners ejected the miscreant from the list. According to Stephen Birmingham’s California Rich: The Lives, the Times, the Scandals and the Fortunes of the Men & Women Who Made and Kept California’s Wealth, any woman who drank more than one glass of champagne was never invited to Mrs. Martin’s house again. Divorced people were never permitted in her home. Birmingham says that she gave frequent and dreadful parties, was intimidating and rude, and her snubs were legendary. Apparently Mrs. Astor in New York outdid her, however, for her doors were completely closed to anyone from California. With Greenway also writing the social column, the dynamic duo in San Francisco could make or break one in society. Compared to that, Santa Barbara downright inclusive.

The Grand Debut

Marguerite’s formal bow to society, however, took place in San Francisco. The Gold and White Ballroom of the Fairmont Hotel saw several hundred guests file into the decorated ballroom for a large reception. It was followed by a dinner party for 50 in the Red Room and then a dance for 150 guests. A supper near the end of the evening brought the event to a close. It was considered one of the largest and most notable debuts of the season.

In March 1911, Peggy and her mother rented another bungalow in Montecito. In between the social events that filled her days (house-guests, dinner parties, golf, tennis, festivities, and luncheons) was a return to San Francisco to perform in a Kirmess benefit. The newspaper described her as one of the “Girls of our 400” – Marguerite had truly arrived. Having achieved victory in the rarified social world, Marguerite – “the million dollar society girl” – also came into her inheritance, and she went on a buying spree.

Intending to make Montecito her permanent home, Marguerite bought five acres of land fronting today’s Cold Spring Road from the artist Elizabeth Eaton Burton. The acreage was planted with citrus and sandwiched between Charles Frederick Eaton’s Riso Rivo (soon to become Lolita Armour’s El Mirador) and Ralph Kinton Stevens’s Tanglewood (which eventually became today’s Lotusland).

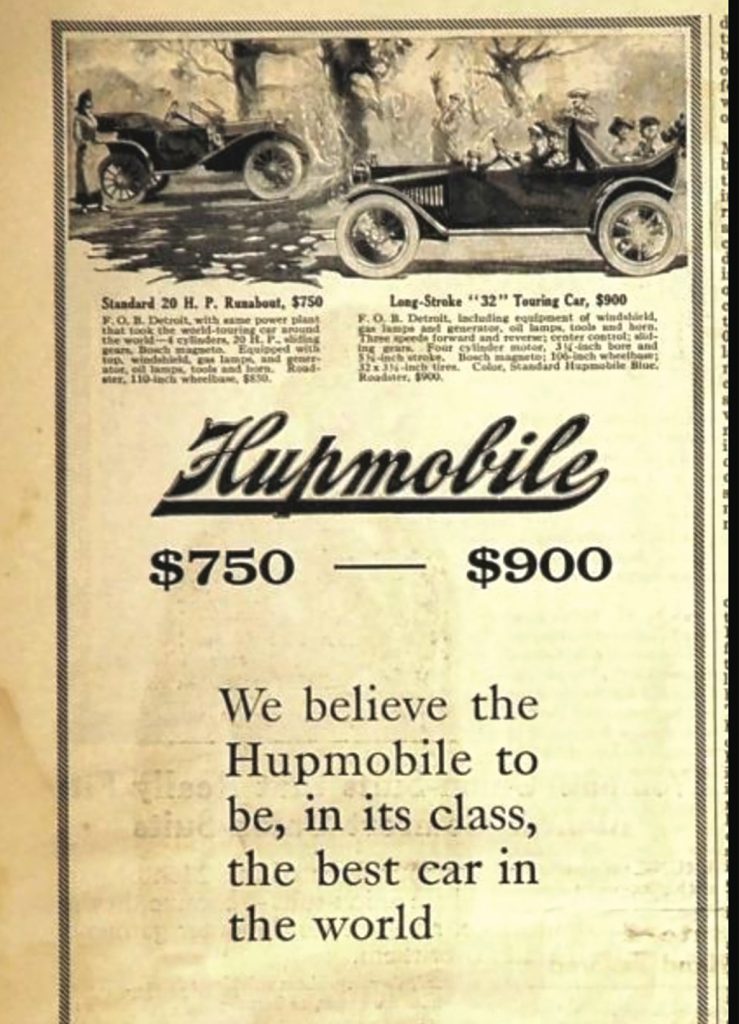

In October, The San Francisco Call reported, “She was immediately admitted into exclusive Montecito social circles and her many new friends were delighted when she purchased five acres in the Montecito Valley. Miss Doe is an expert swimmer, golfer, and horsewoman, and also devotes much time to driving her own car.” Indeed, one of her first purchases as an independent woman was a four-door 1912 Hupmobile Runabout in which she raced recklessly and with abandon along the roads and hills of Montecito.

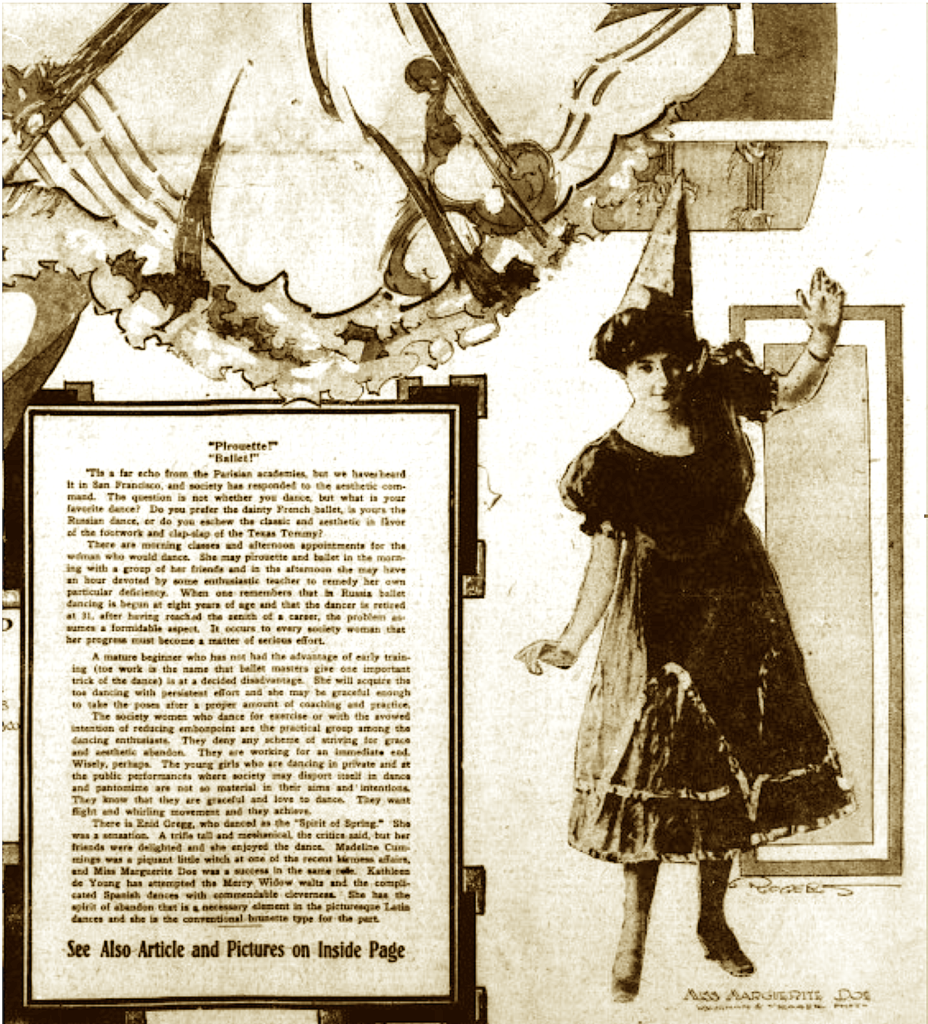

Marguerite, pictured above in her role for a Kirmess benefit in San Francisco, also participated in Santa Barbara’s Neighborhood House Kirmess (San Francisco Call)

Peggy could not resist the sporty Hupmobile Runabout, whose name suited her personality

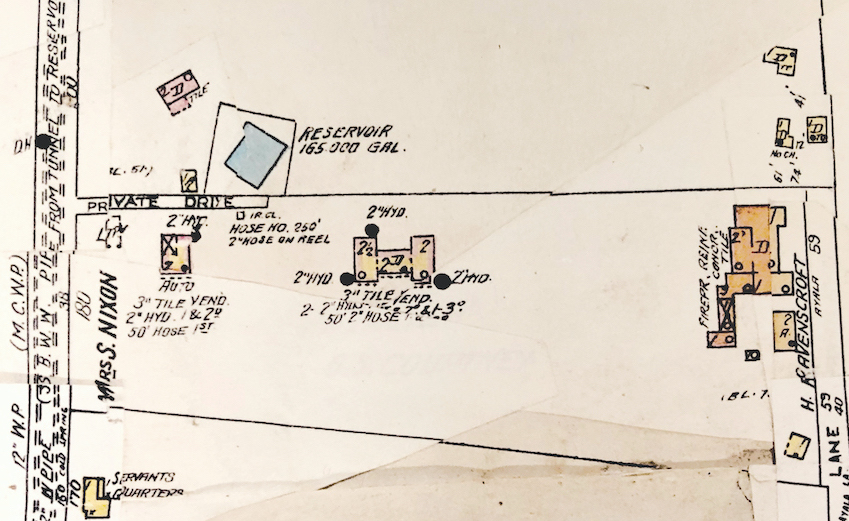

Also that October, she contracted with architect Russell Ray to design a residence and garage. Christopher Tornoe was in charge of construction. The house featured a sweeping view of the valley, channel, and islands from the south and a mountain view from the north. Ray designed an H-shaped frame house clad with three-inch brick veneer for fireproofing. The two wings were connected by a staircase hall, and the living room comprised the whole of the west wing. The dining room, kitchen, and servants’ dining room lay in the east wing. Affected by the destruction of the San Francisco earthquake and fire, she was reassured by the numerous hydrants, hoses, and a nearby reservoir. The second floor contained four bedrooms, dressing rooms, three baths, and sleeping porches. A third story on the west wing contained bedrooms and baths for the maids. As far as landscaping, the orange grove was central, but the house would be embellished with a terrace across the front and a large pergola on the east. There was also a stable, male servants’ quarters, and, of course, a garage.

The Smart Set

Properly debuted and mistress of her own future and wealth, Marguerite continued her whirlwind of social engagements. The San Francisco Call’s “Smart Set” social column (in reporting on the changing attitudes toward unchaperoned unmarried girls) wrote, “In 1912, Marguerite Doe builds a perfect palace – they say it is – in Montecito and lives there quite alone, and no one thinks it at all unconventional.”

In 1913, hardly a week went by that her name didn’t appear in the society pages as attending or hosting some function, but her activities started to include some beneficent and cultural projects as well. In January, she became vice president of a new organization known as Cottage Hospital Bees, whose plan was to sew for destitute maternity ward patients who needed clothing for themselves and their babies. She also volunteered to work at the St. Cecilia Society’s annual Valentine’s Day Fair, which raised money to pay hospital expenses for those who couldn’t afford them.

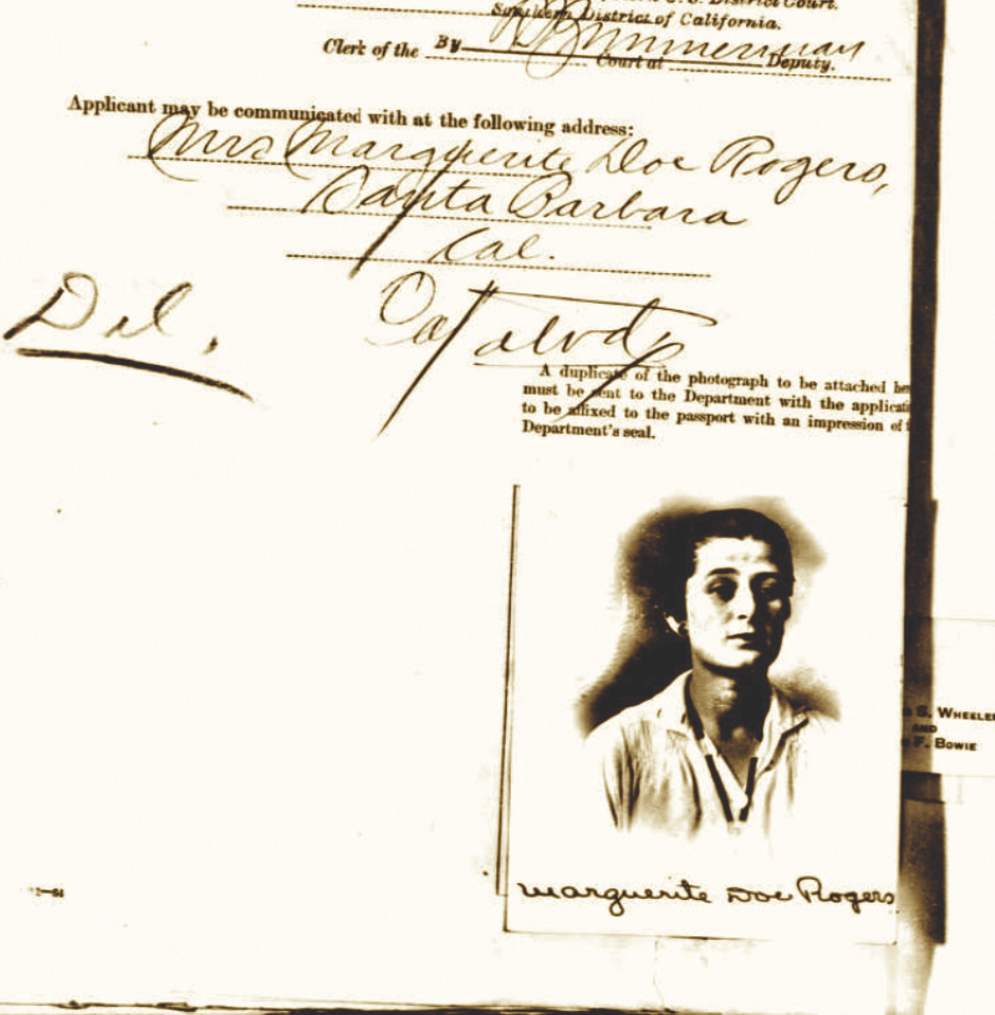

In 1914 the social whirl continued and Eliot Rogers often appeared at the same events and was often a guest at those she hosted. Then, World War I broke out in Europe, and the world grew serious. At the end of October, Marguerite traveled to San Francisco, ostensibly to visit her mother at the Fairmont Hotel. On November 5, her friends were surprised when the local newspapers announced that she and Eliot Rogers had been married in a quiet, simple ceremony at the First Presbyterian Church in San Francisco. Apparently, she’d been carrying around a marriage license to be ready in case she made up her mind to marry him.

War Work

Neither war nor marriage, however, took much spin off their social life, and during 1915 and 1916, the endless merry-go-round of society continued. As the war in Europe ramped up, however, America responded with relief efforts. In September, Marguerite worked at the Russian bazaar for the War Relief Committee of Montecito at the newly completed Country Playhouse in Montecito.

Then, at the end of September 1916, she advertised her 1912 Hupmobile Roadster for sale, saying it would be a bargain to anyone willing to take it at once. It was the first indication that something had shifted. Friends soon learned that the million-dollar society girl was putting aside her partying to join the Red Cross ambulance service in France. What events and discussions led to this bold decision remain unknown, but Eliot was left behind, planning to join her later.

By the end of October, Marguerite and her little dog Geoffrey were en route aboard the steamship Lafayette, which was escorted by a flotilla of destroyers. The crossing took extra time because the ship took the extreme southern route to avoid submarines in the North Atlantic.

In December, word came that Marguerite was doing relief work in France, giving assistance to women and children, many of whom were in the most distressing need of clothing, food, and fuel. She was also planning to return to Montecito early in 1917 or as soon as the menace of submarines in the Atlantic became less threatening.

A Christmas cablegram to her mother and Eliot had this to say:

“In company with several American ladies I went to the Gare du Nord on Thanksgiving Day (which of course means nothing here in France), where we were very busy serving cups of hot coffee and hot bullion to some 1,750 soldiers from the front, who were being sent back to a hospital in the south of France to recuperate. They seemed very cheerful, even though they were convalescing. On the following day, I was on a party from the American embassy to see the presentation of medals to 50 officers and 120 soldiers. The huge courtyard was filled with soldiers ready for the front. There were wonderful bands of music, and it was a very impressive sight, and sad, when the widows came forward to receive their husbands’ medals. General Gallatin presented the medals with the aid of General Dolmand and General Cousine.”

In Santa Barbara, Red Cross volunteers were sewing and packing comfort bags for the soldiers. Each kit contained handkerchiefs, pencil and paper and envelopes, toothbrush and paste, washcloth and soap, small comb, New Testament Bible, shoestrings, gum, Vaseline, tobacco, and a sewing kit. A letter from Marguerite in March said she’d distributed several of the Santa Barbara bags, which she had received through the general headquarters in Paris.

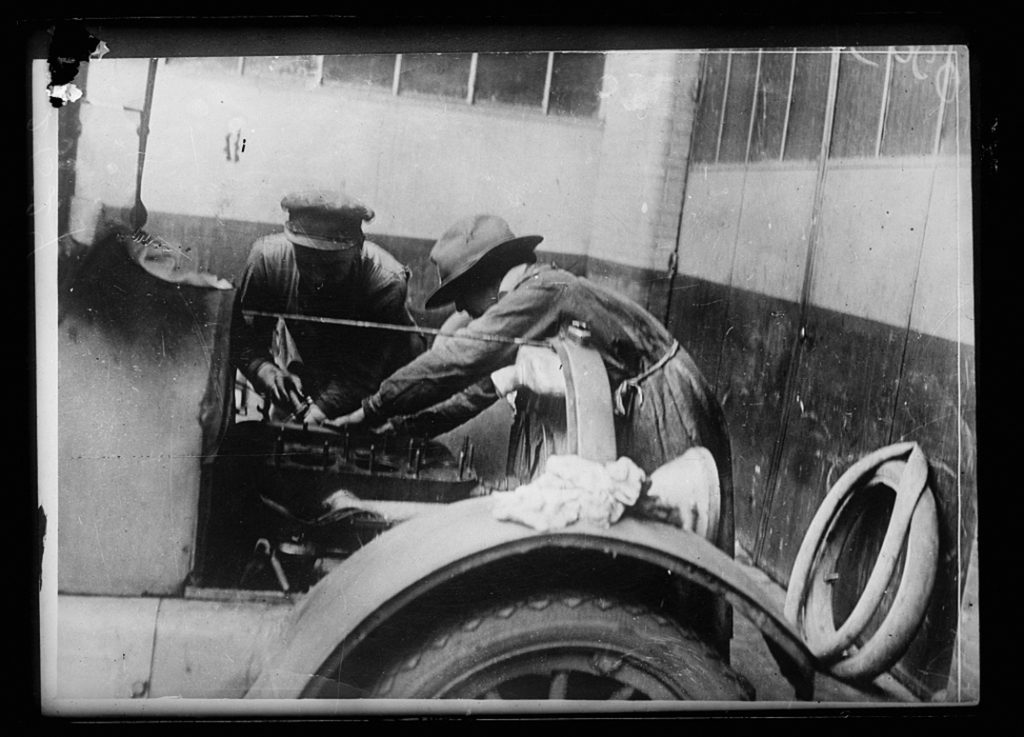

In France, Marguerite drove an ambulance that had been donated by San Franciscans, often serving in places of extreme danger. She also drove a motorcar for the American Red Cross. The San Francisco Call reported, “Because of her skill as a driver, she has been chosen to take machines filled with provisions to the soldiers who are going and coming from the front. This is an extremely difficult and oft times a dangerous task. Mrs. Rogers writes that the usual traffic rules for automobiles have been revised, and machines keep to the left instead of the right, and on the open roads there are no lights and no speed limits.

“As Miss Marguerite Doe, of this city [SF] she was the first society girl to drive her own car. Later, when she went to Santa Barbara to live, she became very proficient in driving over the hills. This experience has proved to great value, as it enables her to drive through places and over roads that would be impassable to the average woman driver. Mrs. Rogers, with her maid, is stopping at a family hotel near the Barrett Fithians, on the Place de la Concorde.…”

At the end of May, Marguerite wrote her mother saying, “Paris is very beautiful now, the trees and parks being particularly lovely this spring.” Considering that the terrifying sounds of war could be heard inside Paris, it seemed out of sync to notice the glories of spring.

In a précis of John Baxter’s Paris at the End of the World: The City of Light During the Great War, 1914-1918, it says, “For four years, Paris lived under constant threat of destruction. And yet in its darkest hour, the City of Light blazed more brightly than ever. Its taxis shuttled troops to the front…the grandest museums and cathedrals housed the wounded…[but] at night, Parisians lived with urgency and without inhibition. Artists like Picasso achieved new creative heights….”

Clearly the heightened awareness of danger also heightened one’s awareness of beauty and light, and Marguerite was not immune to the beauty of Paris in springtime nor to that of a certain young lieutenant of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, English Imperial Army.

Germany capitulated on November 11, 1918, and the fighting stopped when an armistice was signed. The war was essentially over, but Marguerite refused to return home. In December 1918, Eliot filed for divorce, charging desertion. She accepted service of the papers by cable in London, to which she had relocated.

In London, Marguerite did canteen work and assumed charge of a hospital for American and British soldiers, most likely St. Dunstan’s hospital for the blind. The horrible mustard gas used by the Germans had stolen the sight of many soldiers. When Marguerite eventually returned to Santa Barbara, she would raise funds for St. Dunstan’s.

With negotiations for terms of the peace treaty being hammered out at Versailles and an official end to the war imminent, Marguerite made plans to return to the United States via China and Japan. Interestingly enough, a dashing young lieutenant by the name of Geoffrey Stuart Courtney would also be on the ship that arrived in San Francisco on January 22, 1920, six days after Prohibition went into effect in the United States.

The San Francisco Call reported her arrival, saying, “Mrs. Marguerite Rogers is returning home today and thinks it will be difficult to resume her former life. She arrived on the China Mail steamship Nile, by way of Suez Canal and was met at the dock by her mother. ‘I’m coming back to rest,’ said Mrs. Rogers, ‘but I’m afraid I’m going to find it difficult. I’m afraid there will be nothing a servant can do in my house. Military rule has taught me to depend on myself.’”

The article goes on to say that she washed her own car and did her own repairing, and that she was a familiar figure on the battlefronts when the fighting was thickest.

Marguerite Doe Courtney

Lieutenant Geoffrey Stuart Courtney of London, England, traveling with his friend, Colonel George Nutting, had planned to investigate ranch property in Miles City, Montana. Big Sky Country, however, didn’t hold a candle to the vivacious Marguerite Rogers. Nutting and Courtney were soon ensconced as guests at the beautiful El Fureidis estate in Montecito. Santa Barbara friends were once again surprised, however, when newspaper headlines blared “MRS. MARGUERITE DOE ROGERS WEDS: Rich San Francisco Girl Again in Cupid’s Net.” The newspaper revealed that the wedding was the outcome of a war romance three years prior when the bride was in France as an ambulance driver. Once again, the quiet ceremony took place at the San Francisco First Presbyterian Church.

After the honeymoon, the happy couple returned to Montecito where they indulged in a blitz of social engagements and tennis and golf. Two new features were added to their annual repertoire of hosted parties. One was a huge swimming and supper party at Plaza del Mar for 150 friends, and the other a paper chase, a game that imitates a foxhunt. On the day of the first paper chase, 20 friends on horseback gathered on the beach at the end of Eucalyptus Lane. Geoffrey took the role of one of the hares, dropping bits of paper to imitate the scent of the rabbit as he dashed away through the estates of Montecito and the others gave chase, following the shreds of paper.

During this time, Marguerite embraced the style of the 1920s with aplomb. Many years later, her friend Virginia Cherrill Martini, actress and former wife of Cary Grant, said that Peggy had a great figure and wore flapper style for many years, including a cloche hat and everything else that was considered “the cat’s meow.”

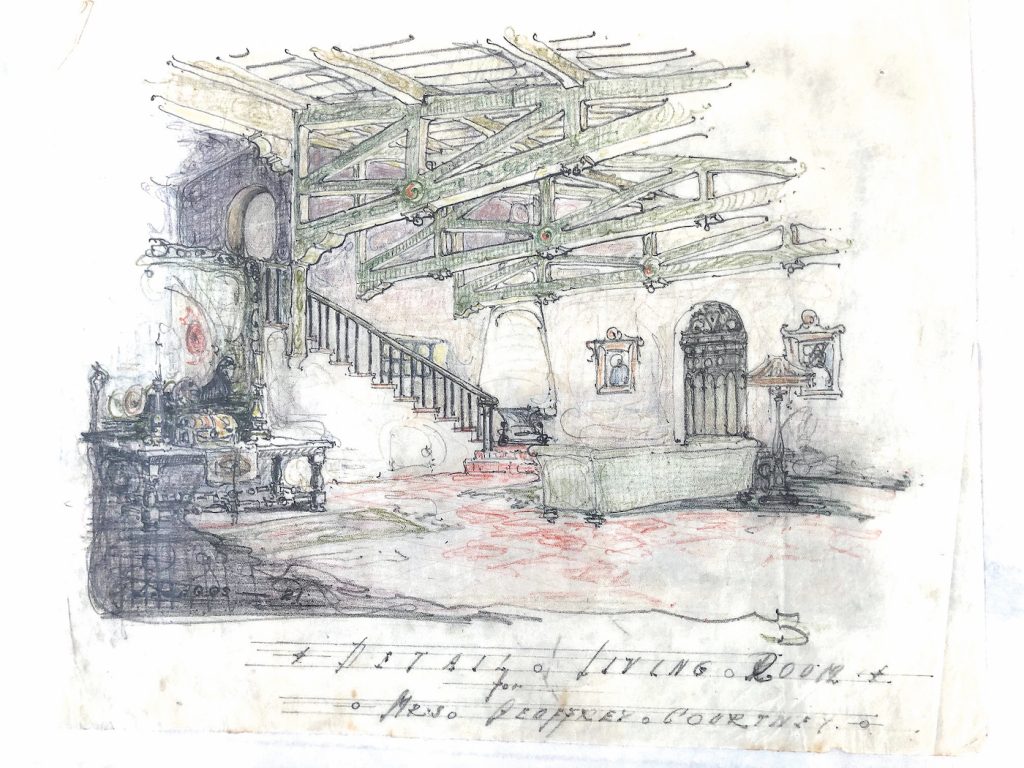

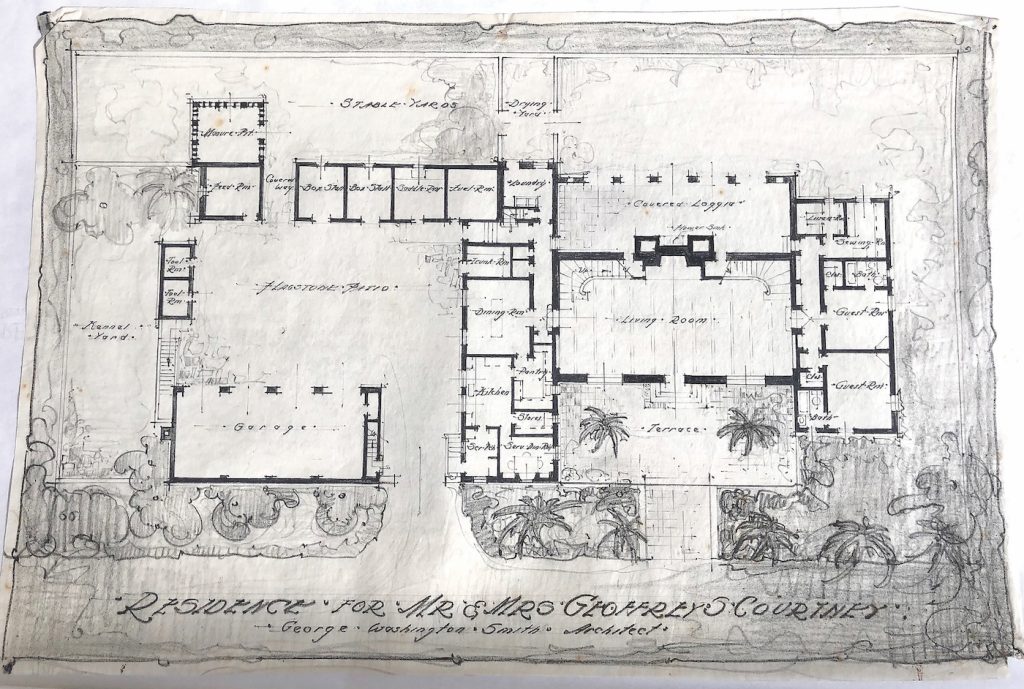

(Right)Floor plan rendering for George Washington Smith’s design of the Courtney residence (courtesy UCSB Architecture & Design Collections)

In 1921, an article in The San Francisco Call tackled the issue of bobbed hair. “That clicking sound is the snip, snip of sheers upon patrician locks,” reported the writer. “Maid and matrons are being shorn and some find it ‘Just the Thing’…. Mrs. Geoffrey Stuart Courtney, who once had a beautiful mass of dark hair, now wears it nearly as short and close as a man’s.”

That same year, Marguerite commissioned George Washington Smith to design a new home for herself and Geoffrey. Presumably completed in 1922, it stood on the eastern side of her property. Casa de Campo, as she named it, was tailored by Smith to accede to her wishes. She insisted the house be built of fireproof reinforced concrete tile. There were to be no moldings because she didn’t wish to dust them. The six tiled garage bays resembled Roman baths and formed one wall of a tiled courtyard, the other being formed by box stalls for her horses. Smith even designed doghouses for her pack of Sealyham Terriers.

The most prominent feature of the house was the grand fireplace of the living room with its surround of two curved staircases leading to the owner’s suite upstairs. Charles’s bedroom suite was on one side of the central sitting room and hers on the other. Today, the house is known as Ravenscroft.

Humane Society

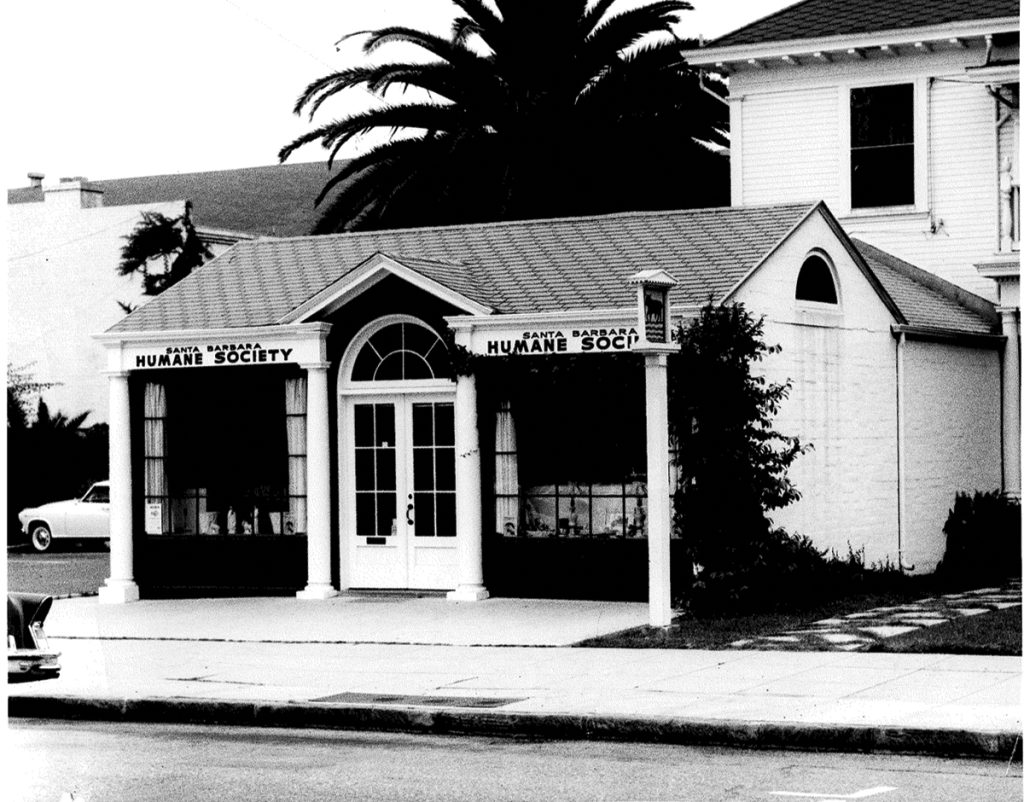

The Santa Barbara Humane Society headquarters and Thrift Shop were located in this building at 1215 Anacapa Street from 1959 to 1961. Peggy was the driving force behind it (courtesy Santa Barbara Humane Society)

Peggy convinced her friends to help staff the Humane Society Thrift Shop on Anacapa Street (courtesy Santa Barbara Humane Society)

By 1922, an interesting change occurred within the society pages. There was less emphasis on party, party, party, and more on cultural events and activities. The lectures and educational opportunities offered by the Women’s Club; the plays, art, and concerts sponsored by the Community Arts Association; and the world-renowned musicians and orchestras brought to town by the Civic Music Committee took precedence, as did philanthropic benefits.

In April of that year, Marguerite was elected to the board of the Santa Barbara Humane Society. For Be Kind to Animals Week, she captained a public drive for two funds. One was for the purchase and operation of a small horse-drawn animal ambulance and the second to provide free dispensary care for sick horses. Booths on State Street were sponsored by local businesses and staffed by society women. In May 1922, she took the oath of office to become a county humane officer, though she only served a few months.

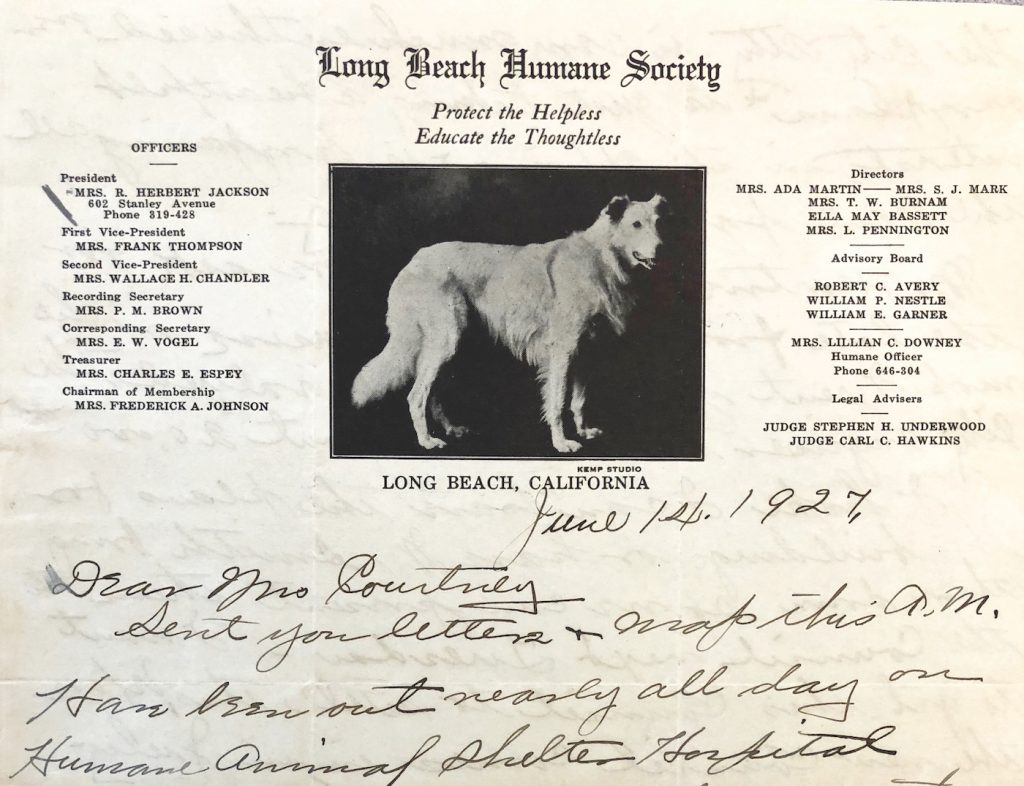

In May 1924, Marguerite and Geoffrey boarded a ship in San Francisco bound for England via the Panama Canal to visit his family in London. Upon her return in August, she commissioned George Washington Smith to design an animal hospital in San Francisco.

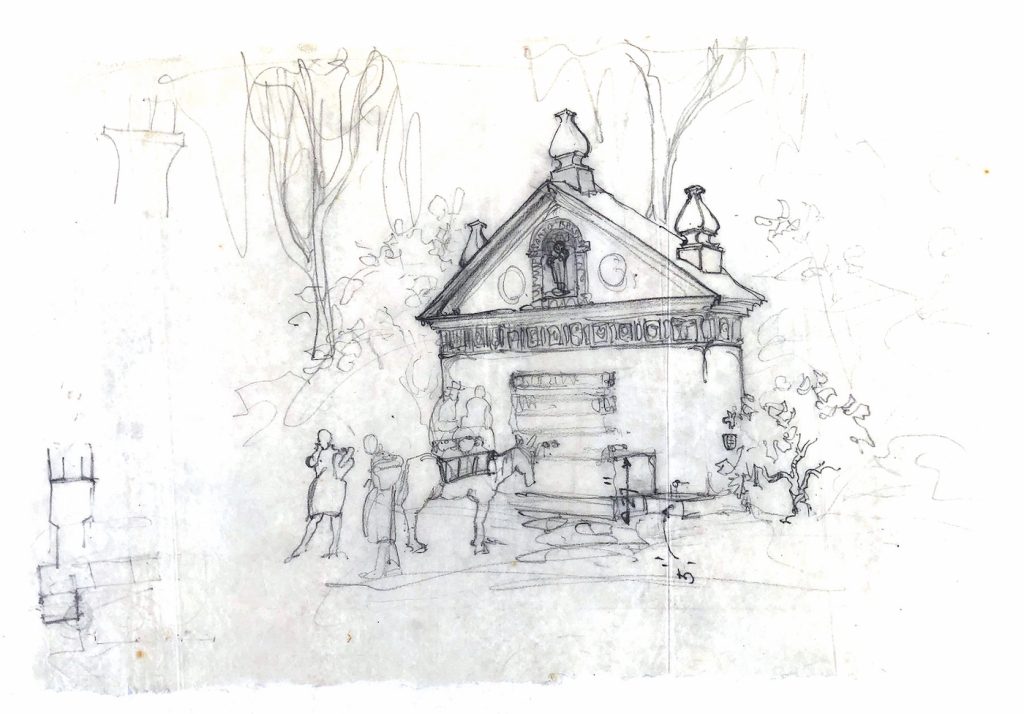

(Right) Lutah Maria Riggs’s rendering of Jack’s Trough (courtesy UCSB Architecture & Design Collections)

Since 1921, the Santa Barbara Humane Society had fought to reinstall drinking troughs for horses which had, they felt, had been inexplicably removed by the city. As the horseless carriage continued to replace the four-legged variety, these thirst quenching amenities had been disappearing all over town. Perhaps that is why in 1925, Marguerite commissioned Lutah Maria Riggs to design a fountain on the corner of Stanwood Drive and Sycamore Canyon Road. Completed in 1926, it was dedicated to her favorite horse, Jack, and offered both a trough for horses and two basins for smaller animals.

Marguerite Doe Ravenscroft

On October 24, 1929, the stock market crashed, ushering in a worldwide Depression. Information about Geoffrey and Marguerite is scanty for the next few years, though they seemed to spend much of those years abroad. In 1930, Marguerite sold off the western portion of her property, leaving herself with approximately one acre on which Casa de Campo/Ravenscroft stands. By 1933, she and Geoffrey had parted ways.

About 1934, Peggy met and married another Brit, Henry Ravenscroft. The marriage didn’t last long, but for some reason, she retained the name, and her home on Ayala Lane became known as Ravenscroft.

Marguerite’s work for the benefit of animals continued for the rest of her life. In 1927 she commissioned George Washington Smith to design animal hospitals in Sacramento and Long Beach. At various points in her life, she had established animal shelters around the world including India, Africa, Indonesia, Egypt, and Ethiopia. She always asked her friends who were traveling in those areas to check on them.

Peggy remained active with the local Santa Barbara Humane Society and served on the advisory board for many years. In the 1950s, she was responsible for opening a thrift shop to benefit animals at 1215 Anacapa Street near Anapamu. (Today, it’s a parking lot.) As late as 1962, she donated a new automobile, equipped as an animal ambulance and a pick-up truck, to Palm Springs Desert Animal Shelter.

Marguerite Doe Rogers Courtney Ravenscroft died in 1970. Besides specific bequests to particular institutions, her will stipulated that her estate be used to fund the Marguerite Doe Foundation for the assistance of animals. Monies from her Foundation allowed the Santa Barbara Humane Society shelter to expand and build the society’s columbarium.

Peggy Ravenscroft may have been a blithe spirit, but the sum total of her life was not frivolous. Her openhanded generosity, bravery, and convivial personality made her a most remarkable woman.

(Sources not mentioned in text: contemporary newspaper sources; ancestry.com resources; Library of Congress; Patricia Gebhard’s George Washington Smith: Architect of the Spanish-Colonial Revival; White Blackbird: A Life of the Painter Margarett Sargent by Her Granddaughter by Honor Moore; UC Santa Barbara’s Architecture & Design Collections; Santa Barbara Humane Society; Sanborn Fire Insurance maps and property ownership maps; transcript of 1985 oral interview with Lutah Maria Riggs with Montecito Association History Committee. Many thanks to Julia Larson of UCSB’s Architecture & Design Collections, to Chris Ervin of the Santa Barbara Historical Museum for his assistance, and to Harry Kolb and Trish Davis.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.