Founding the Granada Theatre

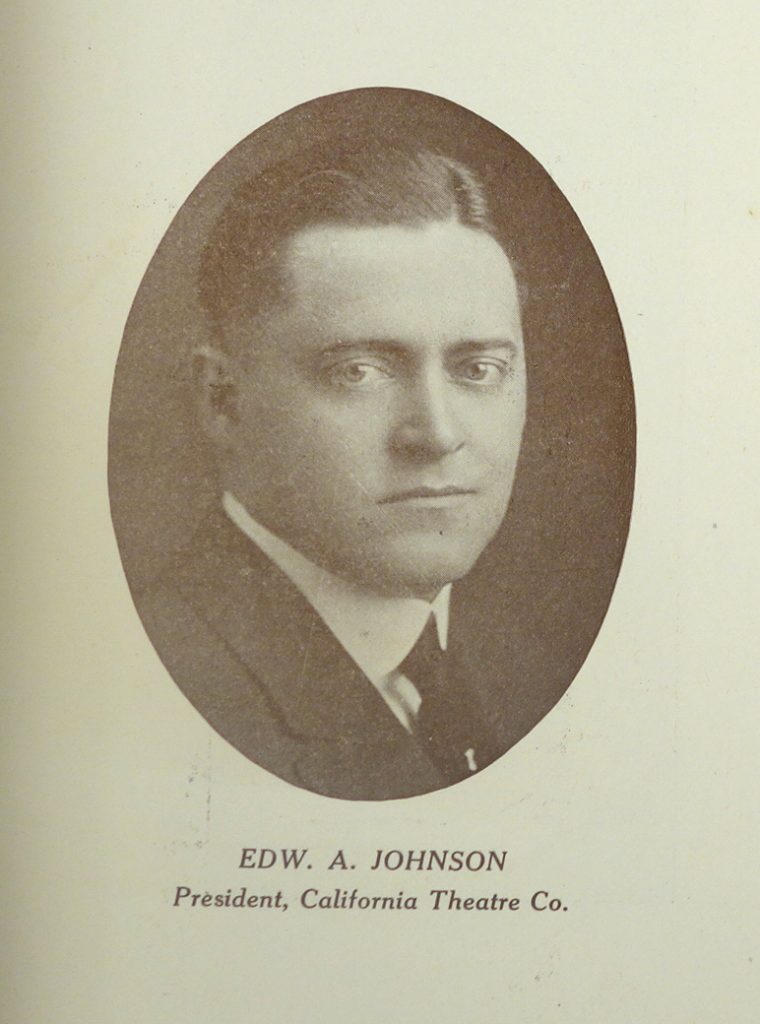

When Edward Johnson, principal stockholder of the Portola Theater Company, purchased the California Theatre on W. Canon Perdido Street in 1920, he envisioned a bright entertainment future for the town. At that time, there were only four movie houses, and one, the Strand Theatre, was being replaced by a motorcycle shop. By 1922, Johnson had incorporated the California Theatre Company and announced an ambitious plan, a grand theater seating 2,000 people in an eight-story office building. While primarily a movie house, it would host live performances as well.

Already in the works in 1922 was the renovation of the old Lobero Opera House which was to become Santa Barbara’s community theater and the main venue for the Community Arts Association’s Drama and Music branches. In February 1923, however, the plan to restore and renovate the venerable theater was abandoned, and a brand new theater design by George Washington Smith and his lead designer, Lutah Maria Riggs, was adopted. The revamped design included the latest in technology and planned to seat 670 people.

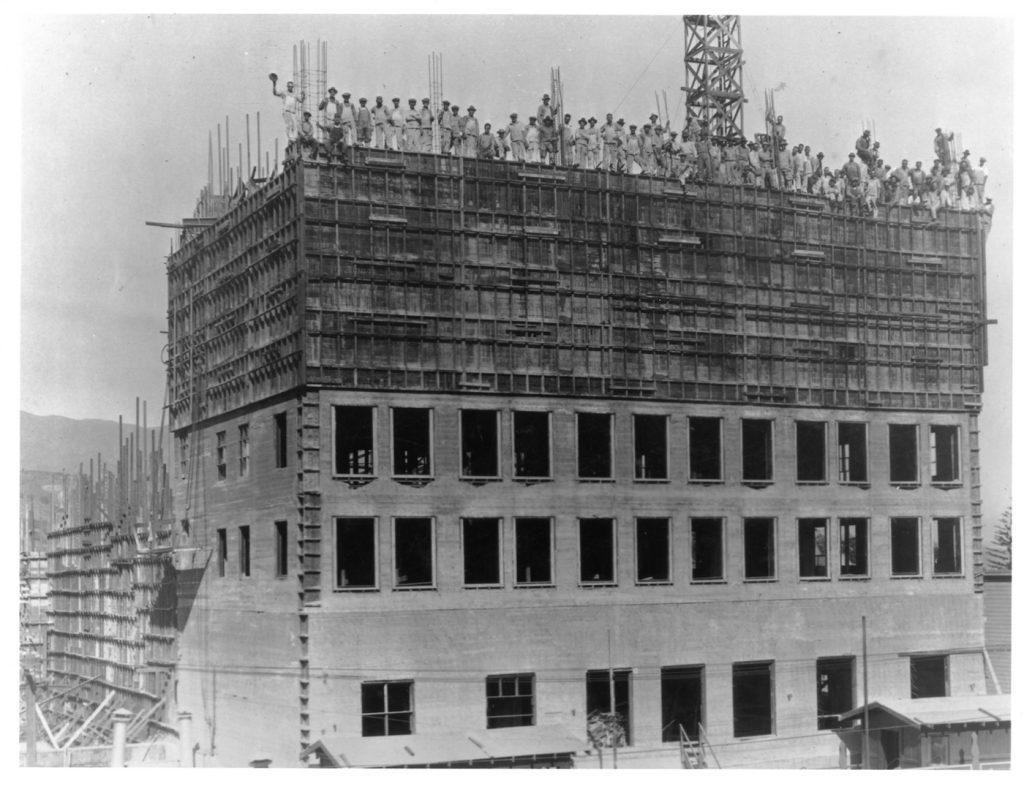

Johnson’s theater was to be much larger, but the plan to erect an eight-story skyscraper in Santa Barbara did not go unopposed. Even his claims that the building was Spanish in design because its façade, with rose and cream terra cotta detailing, and the theater’s interior, which featured elements of Spanish Colonial Revival, did not convince a large segment of the population. (Let’s face it, colonial days in New Spain never saw the likes of a rectangular skyscraper.) Nevertheless, ground was broken in 1923, and on April 9, 1924, three months before the completion of the Lobero, the Granada opened with a grand program that displayed its multifaceted amenities.

The Skyscraper

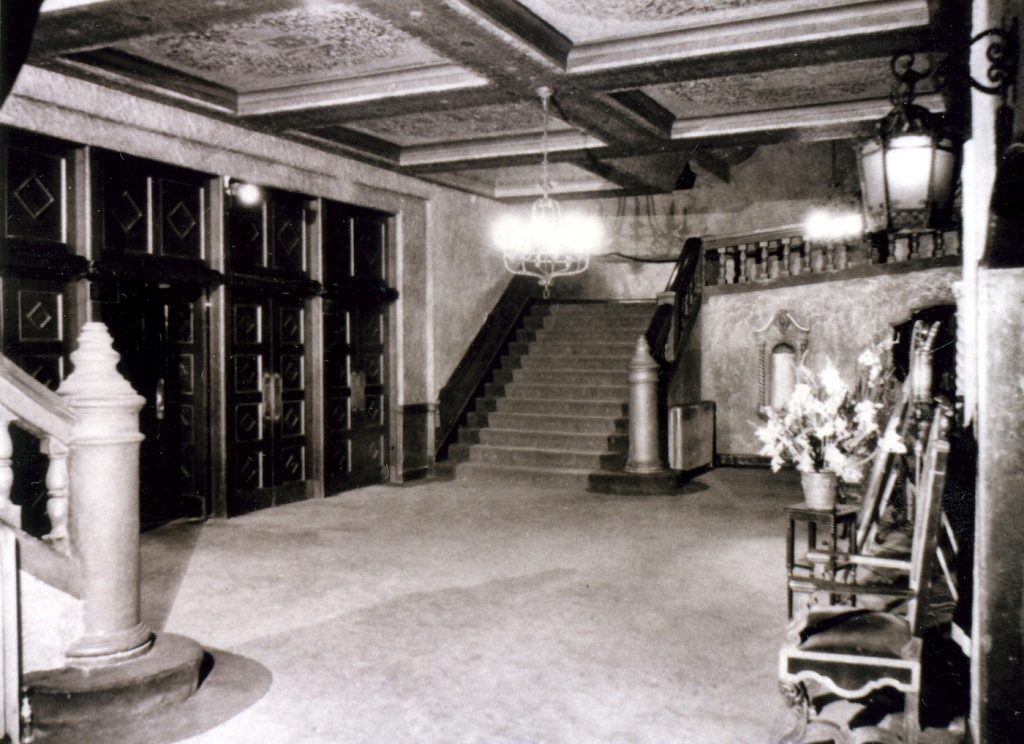

Regarding the building itself, six upper stories contained 70 rooms with all the modern conveniences. Standard Oil Company leased the entire fourth floor and planned to make Santa Barbara its district headquarters. Touting “pure Spanish architecture,” the lobby had travertine walls and elsewhere textured plaster imitating the mode of Mexico. The foyer featured a fountain and fireplace with a niche above it for a statue. Rich carpeting ascending the grand staircase, wrought iron fixtures, stippled walls, handmade furniture, and Moorish detailing all strove for authenticity.

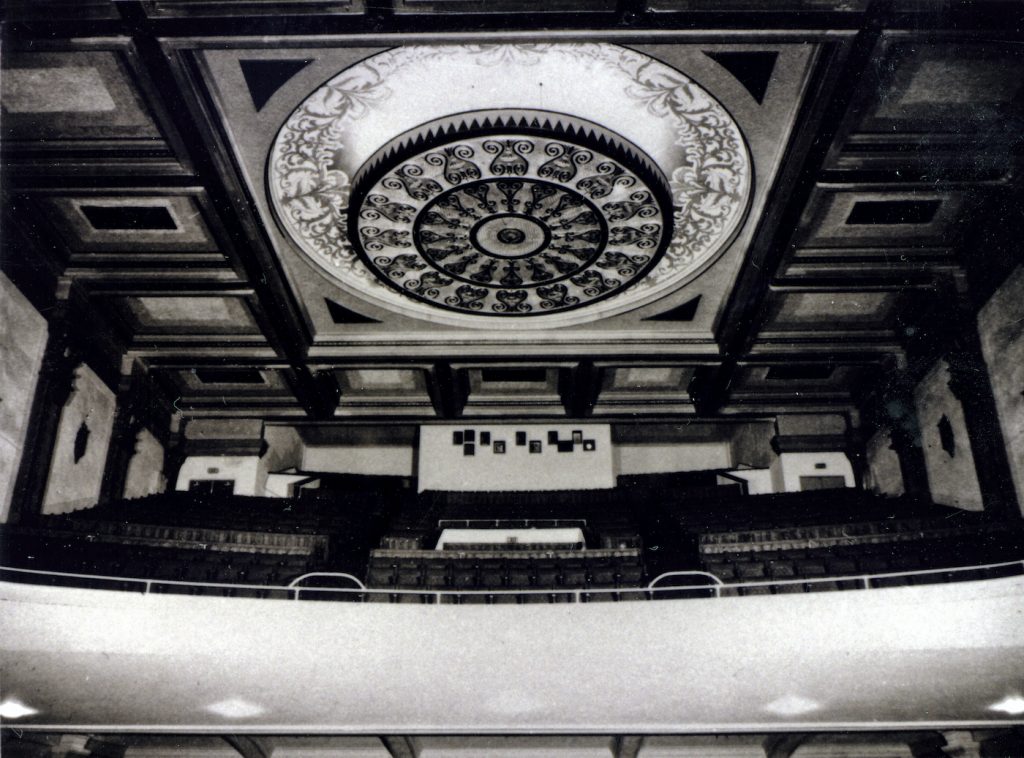

The theater encompassed the first two stories and despite the fact that the advertised 2,000 seats was an exaggeration (in reality, the number was closer to 1,700), the amenities for theatergoers were lovely and included relatively large and upholstered seats. The women’s lounge included a cosmetic room with “snappy” hangings, mirrors, dressing tables, and benches. The men’s lounge included a smoking room.

Twenty-eight dressing rooms in a five-story section near the stage included special rooms with private bathrooms and showers for lead performers and stars. The second largest Wurlitzer Organ on the West Coast would provide the music for silent films. And the ceiling of the auditorium sported a great chrysanthemum disc of light that illuminated the drop curtain, which was painted with a scene of Granada, Spain.

On opening night, the reporter for the Morning Press enthused about “the sumptuousness of its decorations and appointments, its comforts and conveniences, and the splendor of its great pipe organ.” One disappointment, however, was that the scores of movie stars advertised to be present were a no show. The moderator for the evening read “a great sheaf of telegrams” from movie stars extending congratulations but expressing last minute regrets.

Outside, a doorman dressed as a Spanish caballero in a black velvet suit with red and gold trimmings escorted people arriving in automobiles to the door. His three-gallon sombrero with silver ornaments and little red balls hanging from the rim fascinated the girl reporter for the Morning Press, who commented, “He must have tramped in many miles from a rancho way out in the country for the gala event.” Ushers and usherettes were similarly attired.

The Opening Program

Johnson was determined that the program reflect all of what the Granada was capable. His opening program began with “The Granada March” composed by Antonio P. Sarli, “the man who looks like Caruso.” Director of the famous Greater Los Angeles Band, Sarli had initiated the Hollywood Bowl concerts in 1921.

Following the rousing music of the Great Sarli came a Granada Pictoral Review and then a dedicatory address by the mayor of Santa Barbara, Charles M. Andera, whose congratulatory speech was accompanied by an impromptu pipe organ concert. Used mainly to provide musical background and atmosphere for silent films, the organist may have felt Andera’s sober delivery needed a little punch. At this point, a host of movie stars were to be presented, but endless telegrams were read instead.

The audience must have perked up, however, when special red and blue glasses were distributed for the 1922 experimental three-dimensional movie Plastigrams. J. Wesley Lord then played a concert on the mammoth Wurlitzer organ, which was capable of imitating an entire symphonic orchestra.

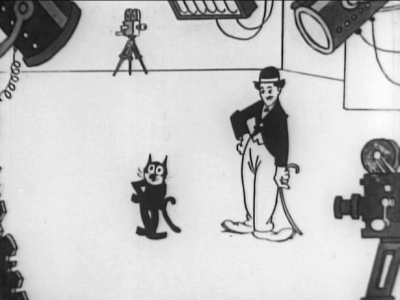

Felix the Cat then entertained in Feline Felix, the Kartoon Kitty. Felix had been created in 1919 by Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer and became highly popular before being supplanted by Disney’s talking Mickey Mouse. Apparently, there was no room in cartoon town for both a cat and a mouse.

Next the Great Sarli conducted his Granada Grand Orchestra in a concert that opened with Friedemann’s “Rhapsody Slavonic.” Friedemann was a German Swiss composer of symphonic music and marches. Sarli followed up with an arrangement of a musical mélange, and then enlivened the audience with his own Syncopated Rhapsody. Toes were tapping by the time the room darkened and the Pathé Review came on the screen. The Pathé brothers were pioneers of the French film and recording industries and had invented the cinema newsreel, hence the name.

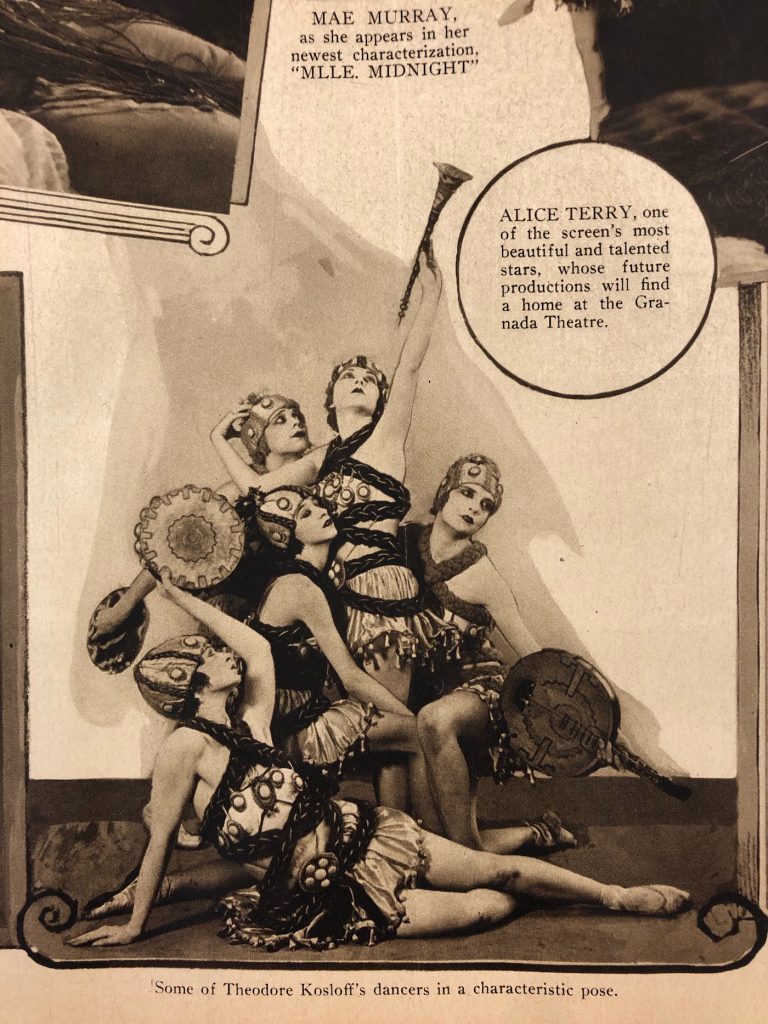

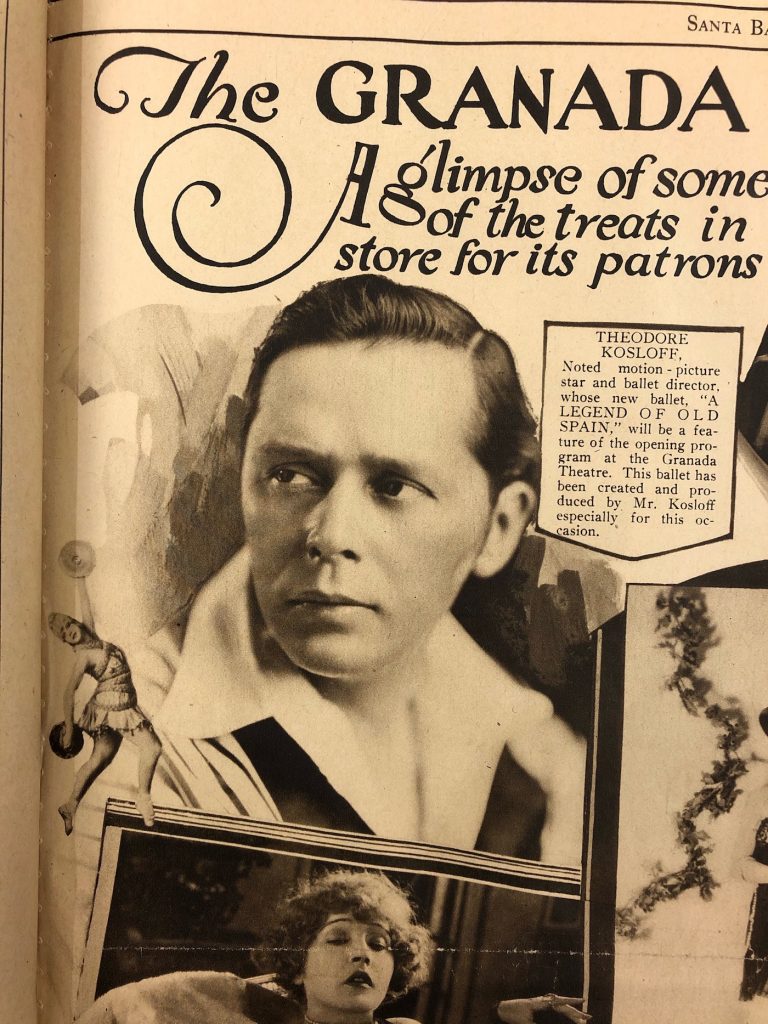

Hazel Kennedy, the “amazingly clever” child clown, warmed up the audience for another novelty reel, and then the screen rose and the curtain opened for Theodore Kosloff’s ballet, A Legend of Old Spain. The Morning Press called it “a gorgeous spectacle of color, form, and movement.”

Kosloff was a Russian born ballet dancer, choreographer, and film and stage actor who came to the United State in 1909. In 1923, Kosloff, for some reason, was offered the throne of the Tatars back in Russia. He turned it down saying, “I could be Khan, but it is doubtful for how long. And I decided I would rather be a live motion picture actor than a dead king.” Unfortunately for Kosloff, the talkies soon killed off his motion picture career.

Then, the part of the program everyone was waiting for, the World Premiere of Mae Murray in Mlle. Midnight. Nicknamed “The Girl with the Bee Stung Lips,” Murray had begun her career as a dancer on Broadway in 1906 with Vernon Castle and later with the Ziegfeld Follies, becoming a headliner by 1915. She moved over to silent films in 1916 and became extremely popular, despite a chaotic private life that included four husbands.

The Morning Press summarized the film thusly: “In Mlle. Midnight, the petite and charming Mae inherits the spirit of a madcap grandmother which leads her into some hair-raising adventures with a bandit chieftain and a wicked uncle, but also into the arms of a gallant Yankee who succeeds after some furious fighting and some hard riding in rescuing her and leading her to the little church across the plaza. The scene of the play is laid in Mexico, so the settings and costumes were thoroughly in keeping with the new theater where it had its first showing.”

Duly launched, the Granada would become the theater of choice for the Civic Music Committee’s 1924-25 concert season. This organization was founded in 1919, the same year as the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, and brought the soon-to-be world-renowned orchestra to Santa Barbara that very first season. The Civic Music Committee was a forerunner of today’s CAMA (Community Arts Music Association), which celebrated its 100th year recently. The full story can be found in Celebrating CAMA’s Centennial: Bringing the World’s Finest Classical Music to Santa Barbara (by yours truly) and available at Chaucer’s Books. (I can’t wait for both the new Granada and CAMA to be operational again!)

(Sources: contemporary news articles including the Los Angeles Times, 14 March 1923, Part 1, Page 11; a plethora of internet searches for basic information about the performers at the opening.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.