For Love of the Land

The Land Trust for Santa Barbara County recently welcomed a new executive director with local roots, Meredith Hendricks, who brings 20 years of conservation, land management, and leadership experience to the County. Her successes with conservation and preservation projects in the San Francisco area will come into play as the Land Trust works to finalize several projects with the potential of increasing the amount of conserved land by up to 15,000 acres by summer 2021, reaching a new total of 45,000 acres. Additionally, Hendricks and the Trust will identify and explore new opportunities to expand community access to natural resources.

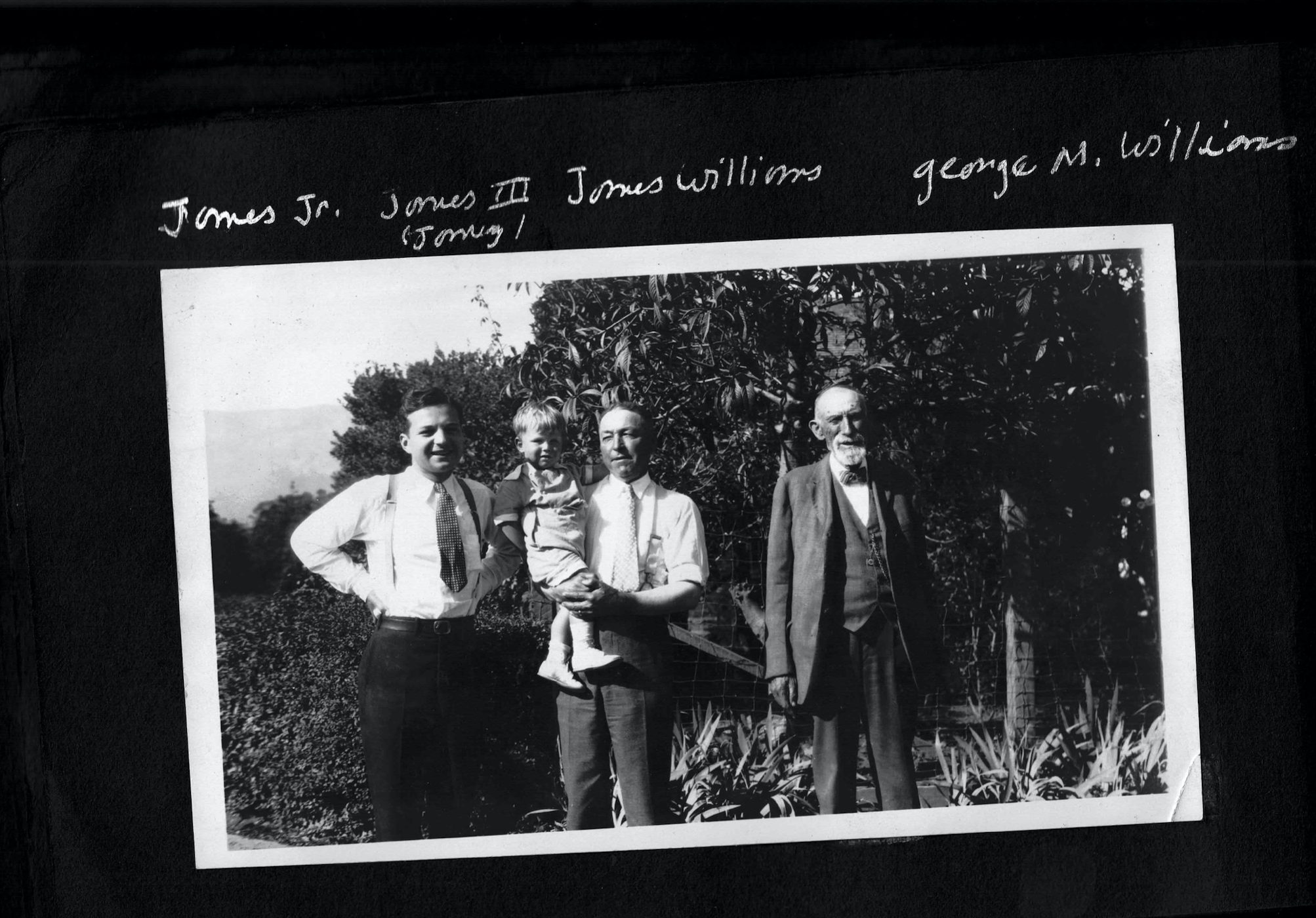

A love of the land, agriculture, and ranching seems to be a part of Hendricks’ DNA for her great, great grandfather, George Martin Williams, was a pioneer Santa Barbara farmer. Meredith is thrilled to be able to reconnect with these roots. Following, is George’s story.

A Pioneer Farmer

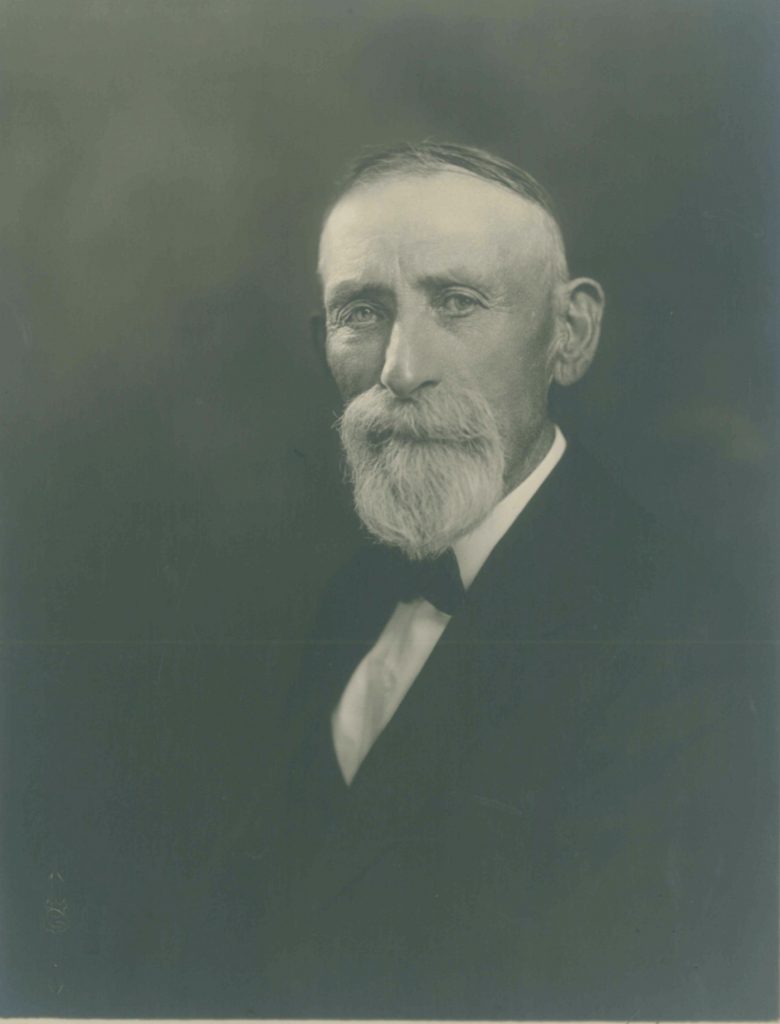

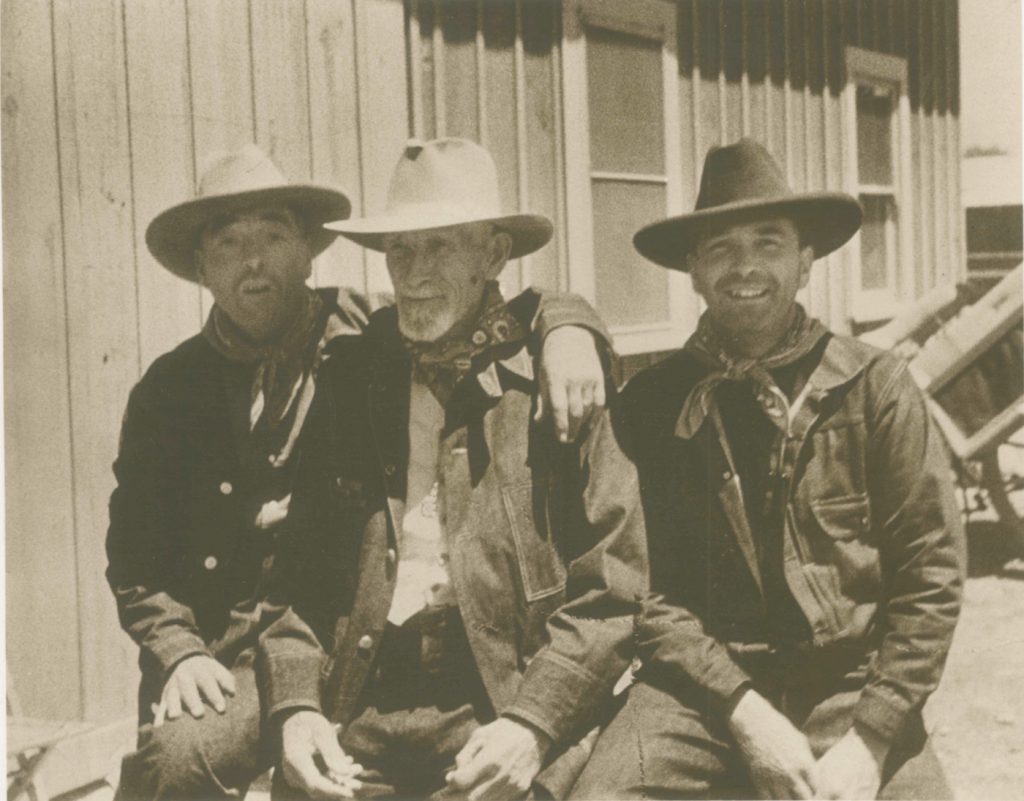

In 1867, a young George Martin Williams arrived in Santa Barbara intending to secure his future and make a living as a farmer. When he passed away in 1935, “Uncle George,” as he had been respectfully and affectionately dubbed, had become known for his wisdom and many contributions to the development of the community. He was a member of an elite group of horticulturalists who originated and developed the agricultural landscape of southern Santa Barbara County.

Born circa 1849 in Baltimore, Maryland, Williams was orphaned by age nine. With few prospects remaining in the East, George left home at 17 and sought his future in the West. He arrived in San Francisco in 1866 and, seeking any sort of work, offered to carry the heavy luggage of a man he happened to meet. This man, who was a cook for a boat leaving for San Diego, hired the young Williams as a cook’s helper, and George worked his way to the southern port peeling potatoes. Six months later, he found a job driving a herd of cattle to Santa Barbara where he found work on a farm. Family stories relate that his mellifluous singing voice had inspired the farmer to offer him steady employment.

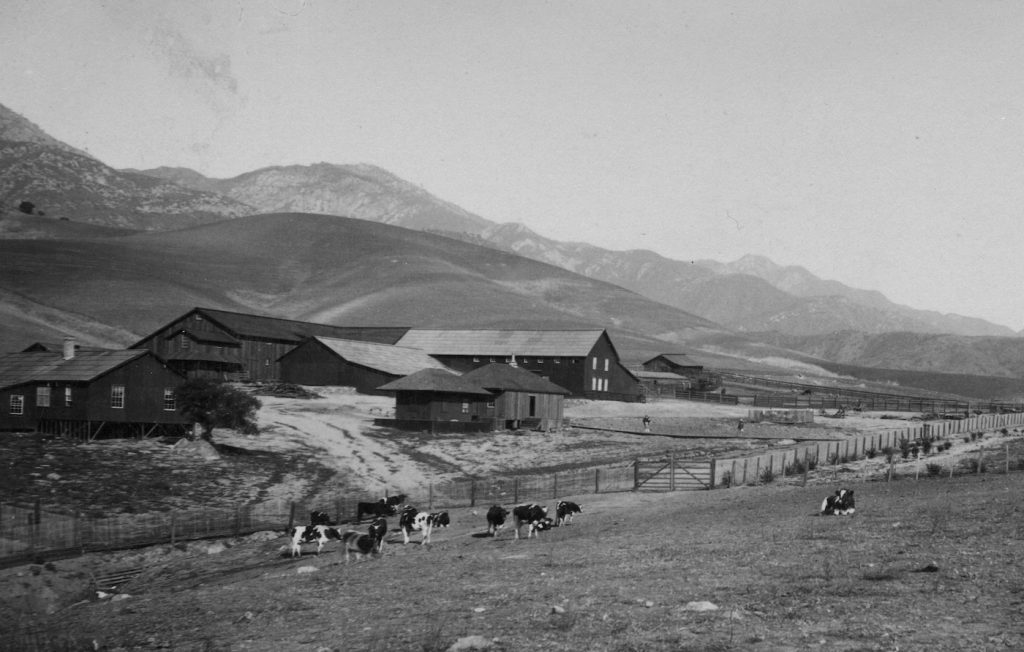

After renting some acres of farmland in 1868, Williams was able to purchase 150 acres on Modoc Road and establish his own farm in 1873. These lands were mostly planted to walnuts.

In 1874, the up-and-coming horticulturalist married Eliza Jane Towne, daughter of pioneers who had crossed the Great Plains to try their luck in California. Eliza and George would raise eight children, only five of whom survived them. George continued to acquire more acreage and by the time of his death owned more than 3,000 acres in various parcels throughout Santa Barbara, Hope Precinct, and Goleta.

Promoting the Crop

It was customary at this time for farmers to advertise their crops by sending samples to the newspaper editors. In return for these horticultural treats, the editors would print favorable comments about the products. George took full advantage of this custom and often received accolades such as “George M. Williams brought in some extra large plums grown at his ranch. They are a new species named Santa Barbara Pride and are worthy of the name.

Another way of promoting one’s crop was to enter the various fairs and expositions. At the very first annual Santa Barbara County Fair in 1881, the Morning Press reported that Williams displayed “large watermelons, the largest weighing 39 pounds, and large potatoes of the Peerless and Peachblow varieties.” The following year, Williams experimented with growing cotton and displayed “a genuine Southern cotton plant with perfect flowers and fully developed bolls.” In 1887, the press reported, “George M. Williams of ‘Orchard Dale’ made the finest individual exhibit of fruits, consisting of 28 varieties of grapes, and a number of watermelons, figs, apples, pears, nuts, tomatoes, and peppers.”

As early as 1880, the local paper touted Williams as one of Santa Barbara’s most enterprising farmers. The article reported, “In the western suburbs of the city he has 13 acres under cultivation. He has another 30 acres on the Arroyo Burro. On the home place he has 1 ½ acres in mixed fruits, with his blackberries being the largest grown in the area. We ‘interviewed’ some of them last August, and should have very little objection to repeating the experience.”

That same year he was already sending his early vegetables to San Francisco. That February and March he shipped 1 ½ to 2 tons of corn, beans, cucumbers, Summer squash and sweet potatoes before most people even had their seeds in the ground. “He has fine, young orchards,” reported the Morning Press, “and his crop of lima beans yielded 11 ½ tons from 12 acres. From this farm never comes the statement that ‘farming won’t pay.’ It is made to pay!”

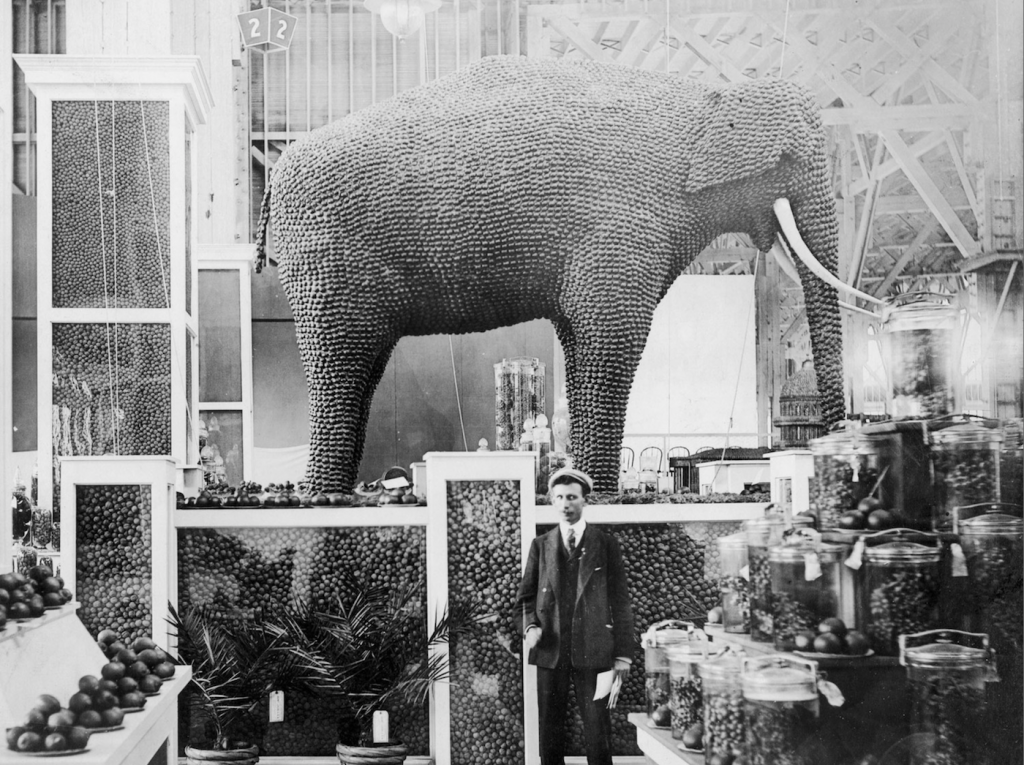

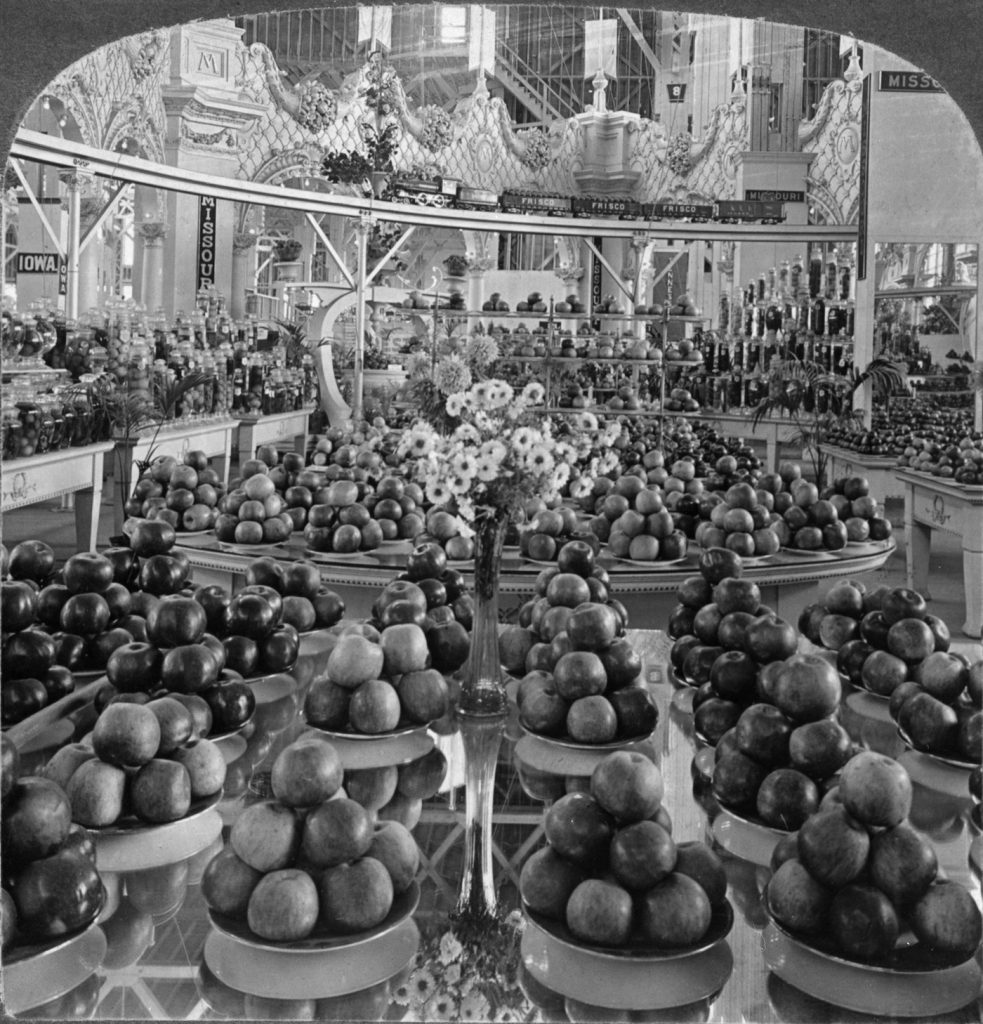

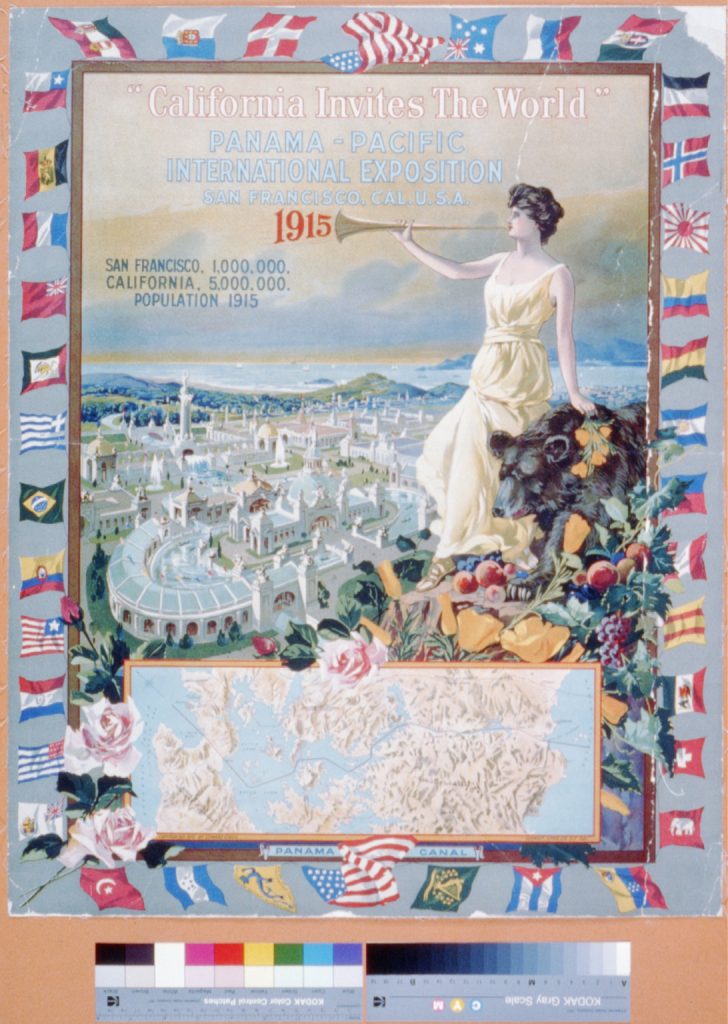

George and other Santa Barbara farmers realized it was in their best interest to send agricultural displays outside the community. His display of apples won first place at the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis (officially dubbed the Louisiana Purchase Exposition). For the Portland, Oregon’s 1905 Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition, Williams became one of five World’s Fair commissioners. In 1914, he was on the committee to solicit entries to the Panama Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

As the fame of his produce expanded, grocers like Thomas Cornwall & Son advertised the provenance of their fruit. One week there would be an ad for canning peaches that were “fresh from the Williams ranch in Goleta; per box, 60 cents,” and another week they promoted “Watermelons, grown on the Williams’ ranch; nice ones; per pound, 2 cents.”

Civic Service

George M. Williams served the community in a variety of capacities. Early on he worked on the Central Committee of the Democratic Party (though he ended his life as a member of the Republican Party). He was adamant about not running for office, himself, however. An article in 1904 stated, “George M. Williams, whom report had prominently mentioned as a candidate for the nomination for supervisor from the Third District, wishes to deny that he has any political aspirations. Mr. William states that at no time did he desire, nor would he have accepted, such a nomination.”

Nevertheless he was a founder of the Santa Barbara County Walnut Growers Association and served as its president for 25 years. He also helped to organize the California Walnut Growers Association and served as one of its directors.

By 1902, Williams had become the spokesperson for Agriculture in the county. That year the newspaper reported his prediction for a great season for the fruit growers. “The peach is the most sensitive of any of the fruits to sudden changes in the weather,” said Williams, “and when the peach trees promise well, the other fruits may be counted upon.” In 1908, the “veteran horticulturalist of this section” said that hay would be but a two-thirds crop. “Most of us were badly fooled by March, a month we depended on for considerable rain,” he said. On through the years, his forecasts peppered the papers.

In 1908 he joined the Good Roads Movement to help pass a bond election to improve Santa Barbara County roads. Always active in helping to get the full vote out, with the vote in 1908 being especially important, he redoubled his efforts to make sure everyone he knew was registered and then to make sure they got out and voted on election day. That year he was quite satisfied with his efforts when he sauntered to the polling table. Once there, however, no one could find his name on the register no matter how many times they looked. The Morning Press reported, “George M. Williams had been omitted from the Great Register… He who had made sure that every mother’s son of his neighbors had registered, had forgotten in the shuffle of events, to perform the same duty himself!”

Luckily, the bond election passed regardless of his lack of vote. He and two others became Santa Barbara County highway commissioners, traveling 1,000 miles throughout the county in nine days to report on roads and make recommendations. They were in charge of construction, awarding contracts, and handling funds for more than 200 miles of county roads.

In 1919, the State of California began to complete a concrete State Highway through Santa Barbara County. As roads improved, automobile traffic increased nationwide, and a proliferation of signs and advertisements grew up along the roadways, on fences, and nailed to trees. Public outcry demanded their removal. When Williams was informed that there was a billboard plastered up against one of his fine trees, the newspaper reported, “He promised to lose no time about making kindling wood of that sign or any other he might find on his premises.”

Banks and Land

In 1903, Williams bought stock in a new enterprise, a California state bank for commercial banking and savings. He became a director of the bank, which was called Central Bank. In 1919 Central Bank merged its commercial side of the business with Commercial Bank, and the name changed to County National Bank. Central Bank retained its saving and trust department, and Williams then became a director of both banks.

All along, Williams had been acquiring land, most of it farmland. In 1888, he bought 52.28 acres of Hope Ranch for $5 from Annie M. Hope. In 1902, he purchased the Daniel Hill Adobe on La Patera Lane plus an adjoining 205-acre tract known as “Williams Flat” from Titus Phillips.

In 1906, he joined a group to buy the Roberts-Cassel ranch of 212 acres in Goleta, one of the most profitable walnut orchards in the county. “George M. Williams, one of the more successful ranchers in this part of the state,” reported the Morning Press, “will manage the property.” Williams owned 30 percent of the corporation.

In 1916, he bought 175 acres of the Ealand Meat Packing Company’s lands in Sycamore canyon. About 70 acres of were suitable for farming and “will be developed along agricultural lines in the efficient manner for which the Williams family is noted,” reported the Morning Press.

In 1920, he bought 91.78 acres of the Dixie Thompson Ranch. “He intends to give Santa Barbara a fine residential section at the west gate of the city limits. The soil is good for walnut orchards and lesser crops,” reported the newspaper.

When George passed in 1935, his sons James and Charles carried on the family business of farming for many years. Older family members, since passed themselves, remembered George as a good and honest man who lived by the Golden Rule. He certainly lived a life of great consequence to Santa Barbara.

‘The Land Through his Eyes’

Meredith Hendricks says she has strongly identified with Williams for a long time. Though they have different beliefs, she shares his extreme focus on work, commitment, and the integration of self into the community. She felt compelled to come back to Santa Barbara to serve the community and enhance the quality of life through the preservation of open spaces and the construction of partnerships that allow ranch families to thrive while remaining in agriculture.

“I would have loved to walk the land and kick some dirt with George,” she says. “I would have loved to see the land through his eyes.”

To learn more about Meredith Hendricks and the Land Trust for Santa Barbara County, go to https://vimeo.com/471569245.

You must be logged in to post a comment.