There Will Be Water

On November 10, 2011, the Montecito Water District (MWD), which was created to provide residents with drinkable water, will celebrate its centennial anniversary. It’s an auspicious occasion, because Montecito doesn’t really have any water, at least none you can find under the soil. In fact, according to countless studies – okay, only 18 studies – our underground aquifer has always been leaky and unreliable. And the 1,000 or more private wells (nobody really knows the exact number) that have so far been drilled into the earth hasn’t helped matters.

Yet several times throughout the past century, the MWD has miraculously managed to find new sources of water, in each case, just in time to solve this age-old dilemma. In recent decades, although Montecito’s population has stabilized, the town still ranks as one of the most lopsided water users in California, with 85 percent of our collective supply used for landscaping as opposed to interior household needs. On June 25, Montecito’s water board plans to solve this never-ending water crisis yet again. After a public hearing on that date, the water board is expected to vote on whether to purchase a 50-year supply of desalinated water from Santa Barbara. The current debate over desalination has its roots in a recent extreme drought that produced a heated water board election season in 2016 which unseated the water board’s previous leadership. However, that particular political battle was just the latest skirmish in a century-long war over how to deliver water to this reliably bone-dry burgh.

Previous articles in this series on Montecito’s complex water world have detailed the arguments both in favor and against MWD’s most recent plan to solve our ongoing water crisis. But to truly understand this latest battle over our collective water future requires a closer historical examination. Of course, given that this story is about the Wild West of California water politics, there’s a wonderful, if misattributed (to Mark Twain, no less) witticism that’s worth mentioning. “Whiskey is for drinking,” Twain’s supposed saying goes. “Water is for fighting over.”

Drill Until Dust

One hundred years ago, Montecito was prime cattle grazing territory, a gentle sloping expanse of wide open grasslands dotted with the occasional oak, sycamore or bay tree, a far cry from the lush paradise we know today. A century earlier, trees were everywhere, but over the decades, early settlers had cut much of the natural forest down for firewood. “They had to get their fuel from somewhere,” said local historian and Montecito Journal contributor Hattie Beresford.

In the 1870s, a town ordinance prohibited the cutting down of coastal oaks. Still, by the 1890s, Montecito’s water-siphoning trees were all but decimated. After the native Chumash people, Montecito’s original inhabitants were Spanish soldiers attached to Santa Barbara’s Presidio and who were granted land in lieu of pay and a pension at the end of their service. Because the shallow wells of the day failed to deliver much water, they built their small farms near the creeks that swelled with winter rains every year. “There was enough water to support that small population,” said Beresford.

But as American farmers moved in the second half of the 1800s, both the creeks and the drinking wells went dry each summer. “When the wells dried up people closed their homes for the summer,” said Beresford. “Speculators began buying land to sell to Easterners looking for winter homes.”

Frustrated by the relative lack of water and the fact that there was no train to deliver their berries to market before they went bad, farmers morphed Montecito’s agrarian landscape into citrus groves during the 1880s. When that succeeded, water became scarce yet again, and for the first time, it became obvious that wells alone wouldn’t solve the problem. The next solution: the construction of a series of horizontal water wells, essentially tunnels that were drilled at a slight downward angle from north to south which delivered water from the other side of the coastal mountain range to Santa Barbara and Montecito.

To pay for the construction of these concrete-lined tunnels, a dozen private water companies sold shares of the supply to local stakeholders, which was distributed via a network of redwood aqueducts. These aqueducts ran into a so-called division box that divvied up the water via a system of “miner’s inches,” which referred to the diameter of the hole that each customer had in the box, which, in turn, determined the volume of the water they received.

“That worked for a while,” Beresford continued. But as more people moved into the Santa Barbara area, the city purchased land in Montecito, and began diverting water from Cold Spring Canyon, which led to several lawsuits over water use, and ultimately, the creation of the MWD itself. By 1920 the time had come, as it so often would come again, for Montecito to find its own supply of new water.

Dam It All

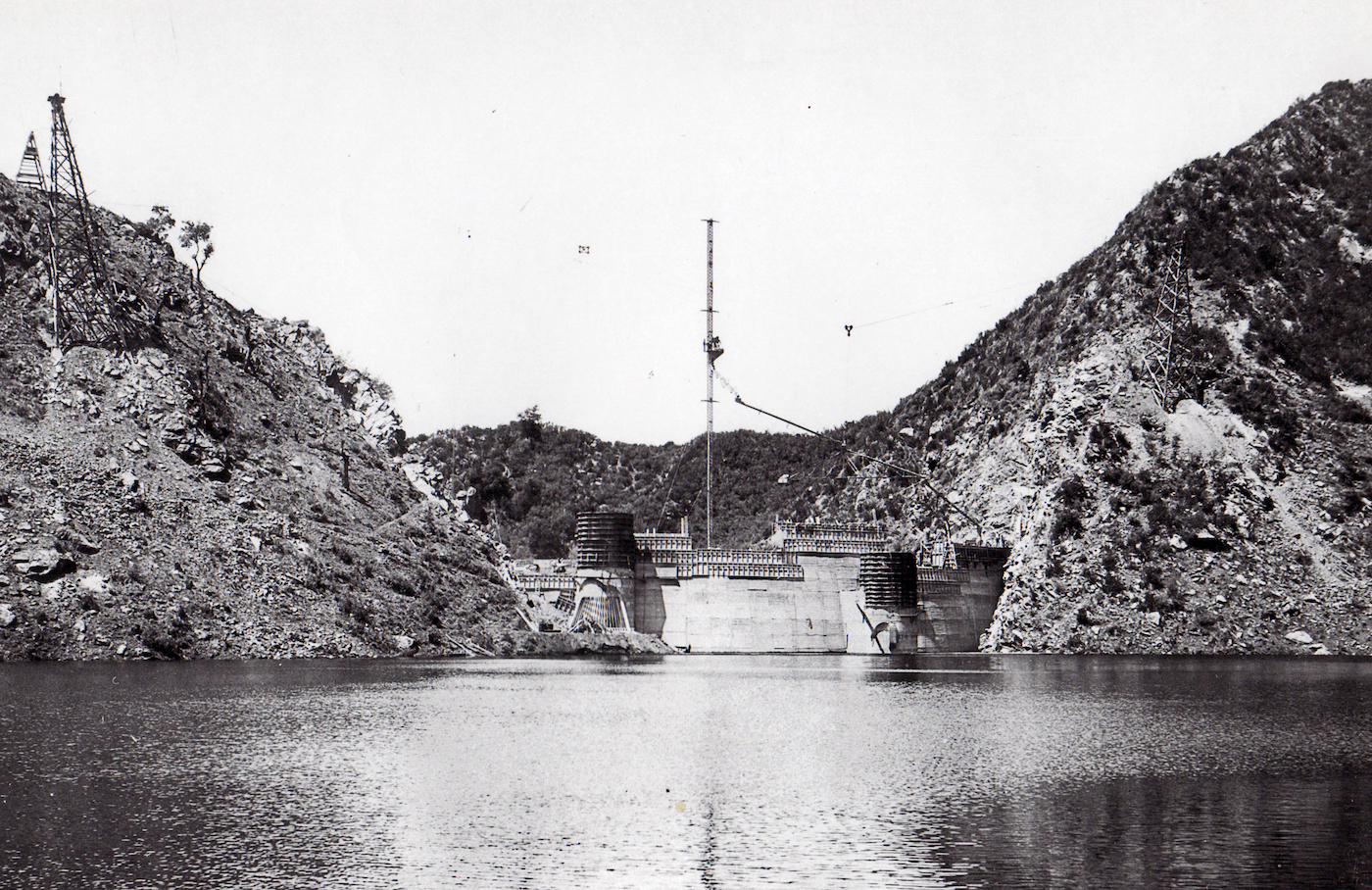

After its official formation in 1921, the Montecito Water District immediately began construction of its first major series of water projects, a series of reservoirs and tunnels carved into the terrain, including the Juncal Dam project which featured a 60-million-gallon reservoir, an 11,376-foot long tunnel, 35.64 miles of cast-iron pipe and no less than 340 fire hydrants. The reservoir and dam took nine years to build and cost taxpayers a grand total of $2.6 million ($39 million in today’s dollars), according to an October 1930 article that ran in Western Construction News. The story referred to Montecito as a “high-class residential section” lying immediately east of Santa Barbara where in recent years “the struggle for water” had become “acute.”

Just on schedule, Montecito began to run out of water again about 30 years later (is that why mortgages are 30 years?), and in 1958, MWD responded with the opening of the Bradbury Dam, which created a second reservoir, Lake Cachuma, which remains MWD’s largest local reservoir. Everything worked great until California experienced a different epic drought that lasted for two decades. In 1973, Montecito declared a water emergency, and the next year refused to issue any new water permits for the next 20 years, a period of water scarcity that led to a rush on the drilling of private wells and the gradual depletion of its aquifer.

A March 1980 report on Montecito’s underground water basin found that the volume of water pumped from private wells each year had plummeted from 1929 to 1979, from a high of around 1,700 acre feet to less than 750 acre feet per year, with over-pumping of wells too close to the beach having resulted in the intrusion of salt water. To fix that problem, the report recommended a limit on local well pumping as well as “an aggressive program of monitoring existing coastal wells.” Historically speaking, the first half of the1980s were relatively kind to Montecito’s water supply, with the groundwater basin reaching its historic height in 1983. But by the mid-1980s, the ground was drying up again. An August 5, 1987 report warned MWD against constructing a line of municipal wells along the coastline, arguing that the only way to find water would be to drill much deeper wells. A subsequent hydrological assessment commissioned by MWD in the early 1990s recommended that the district look to other, more remote sources of water. “It is recommended that MWD not increase pumping duration,” the report stated. “The current five days on and two days off schedule,” the report concluded, “does not allow full recovery in two days.”

Voters Weigh In

By 1991, both Montecito and Santa Barbara were locked in yet another epic, drought-related water shortage. For the second time since county voters were first asked about state water in 1979, Montecito residents were given the opportunity to approve either a desalination plant in Santa Barbara or an agreement to purchase state water from California’s State Water Project (SWP), a series of pipelines constructed in 1968 which brings water hundreds of miles from north to south through the Sacramento River Delta.

Originally, a so-called “poison pill” in the language of the voter’s desal initiative existed that would have allowed whichever plan that received the most votes to proceed while blocking the runner-up. However, the crucial verbiage was missing from the final draft of the desal initiative’s signature petition. More than 80 percent of voters approved the desalination plan, which was backed by the Environmental Defense Center (EDC), while about 60 percent of voters approved the proposed deal to purchase state water. “A grand compromise was reached,” said Carolee Krieger,who campaigned on behalf of desal for EDC and now represents California’s Water Impact Network (CWIN), which still supports desalination. “The mix-up,” she said, “enabled both plans to go forward.”

According to Krieger, the main proponent of the SWP within the Central Coast Water Authority (CCWA) was the Santa Maria Water District, which needed as much water as possible for agriculture yet lacked the financial leverage to negotiate with the SWP by itself. Santa Maria controls more than 50 percent of the vote on the CCWA board. From 1991 to 1995, by which time CCWA’s headquarters had moved from Santa Barbara to Buellton, Krieger attended the agency’s board meetings. What she learned during those years soured her on both the SWP and regional water politics. “The CCWA has been trying to get the contract for state water away from the county of Santa Barbara,” Krieger said. “This would mean not only that South County would lose control to Santa Maria, but that we would have to pay any debt through our property taxes if there was a default on the agreement by any water agency. Nobody has any idea this has been happening.”

Tom Mosby served as MWD’s general manager from 1990 until 2016. He remembers sitting in an early 1990s board meeting where Santa Barbara water officials asked counterparts in Montecito and Goleta to commit to a long-term desal deal. “You guys told us to build the desal plant,” the officials said. “Here’s the contract: Sign it.” According to Mosby, an uncomfortable silence followed. “The board,” he recalled, “was like, ‘Are you kidding?'” Ultimately, Mosby said, Montecito and Goleta agreed to pay about $1 million per year for a period of five years simply to have a backup supply of desalinated water. Because of substantial rains during those years, however, none of that water was ever needed. Instead, Montecito and other local water districts that make up the Central Coast Water Authority (CCWA) agreed to purchase $6 million worth of state water per year, a deal that continues to this day.

To Desal or Not to Desal

Because the much-vaunted State Water Project was a relatively late arrival to the list of projects with claims on California’s water, Montecito’s claim to state water is far down the list of preferred customers. In any case, Montecito didn’t begin to receive its annual allocation of state water until 1998. “At first, we didn’t really need the water, because we had an El Niño season and one of the highest rainfall years on record,” Mosby recalled. As usual, everything went well until California hit another epic drought in 2014. “What happened that year surpassed anything we had ever seen on record,” he said. “The previous biggest drought was from 1947 to 1952, but this was far worse, and we had 1,000 more service connections since then because the community had grown.”

All of a sudden, Montecito found itself in a position where there was no rain, the century-old local reservoirs were bone dry, and state water wasn’t capable of making up the difference in demand because California could only allocate five percent of the contract amount to each of the 29 contractors, including Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. “We set records of demand in the middle of the drought, and then we had no winter weather,” Mosby said. “All of a sudden we had a significant number of more people being served and no conservation measures in place, and that’s why the tiered water system was finally put in. For several months, MWD held up to three board meetings per week to discuss different plans to both put in place conservation measures and obtain more water. “That’s why the tiered water system was finally put in place to encourage conservation,” he said. In March 2014, MWD warned customers, especially heavy consumers of water, that they would have to cut back. That month, no fines were issued, but in April, although 80 percent of water users were told they could continue to use the same amount of water, MWD began to institute penalties for anyone within the remaining 20 percent of customers who went over their allocated monthly allowance of water.

“It worked,” Mosby said. “The change in water usage over the next two months was a decrease of 50 percent. It was incredible. It wasn’t the Water District that did this, but the community itself, which listened to where we were and got the message to use water in accordance with the new rules. I was very impressed: They stood up and stopped using water and allowed us to get through the drought. Montecito is in a much better stance today than in 1990,” Mosby concluded. “This has nothing to do with desalination or a dwindling water supply, but with the ability of the public to realize over time just how important it is to conserve water.”

But not everybody agrees that the water rationing which MWD instituted under Mosby’s tenure was the correct solution. And as previously reported in this series, the subsequent controversy over water rationing led directly to Montecito’s contentious 2016 elections over the future of the water board. It also led to the end of Mosby’s career.

Next week in MJ‘s ongoing series on Montecito’s Complex Water World: A deep dive into desalination.

You must be logged in to post a comment.