‘A Time of Innovation’: Santa Barbara-area Schools Wade into the Uncharted Territory of ‘Remote Learning’

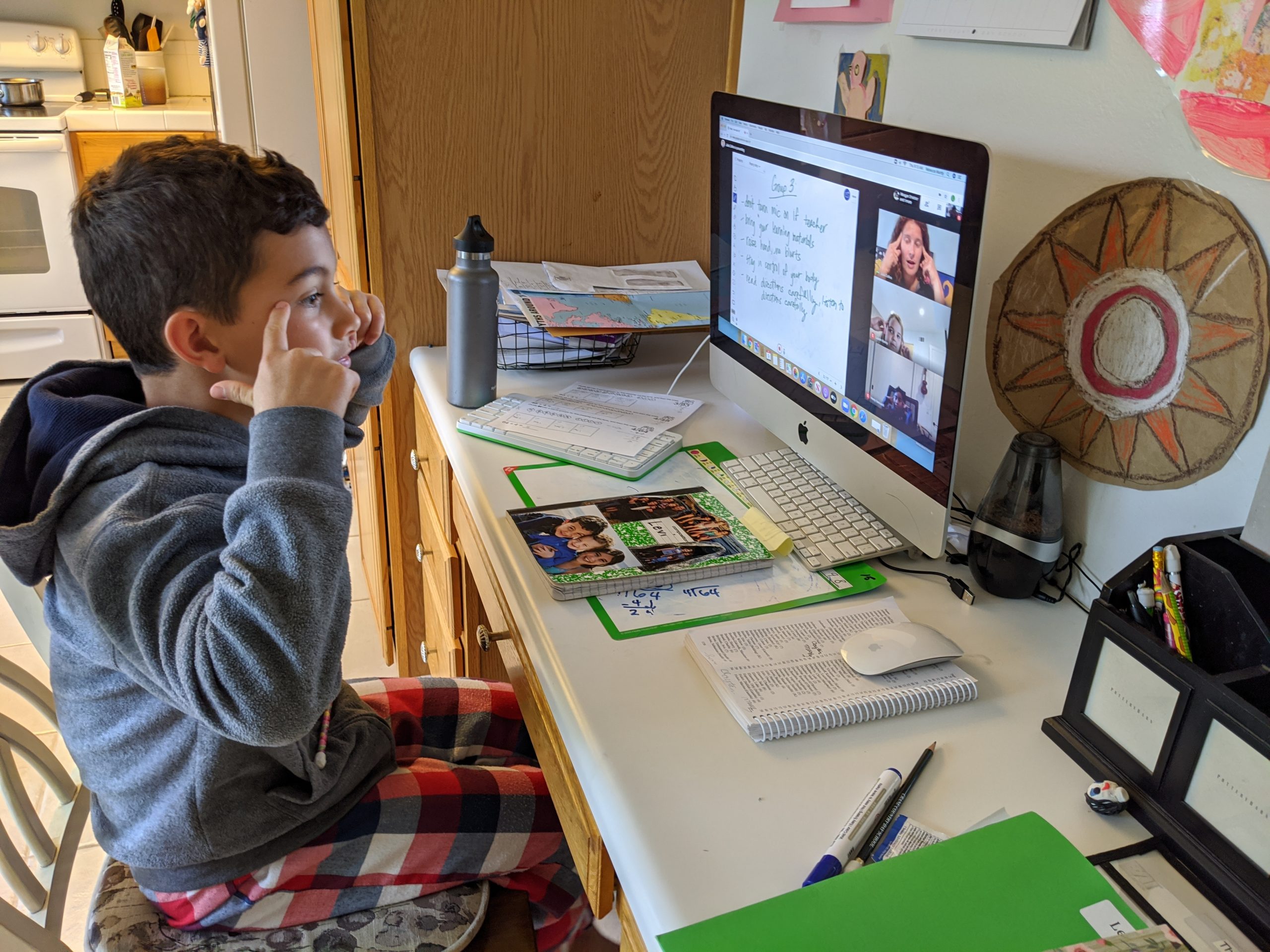

On Friday, March 13, yes Friday the 13th, all schools in California, public and private, closed their doors for the foreseeable future. Then Santa Barbara, like much of the rest of the state, had at most a single week to switch to an entirely new, online model of education, by now known to most as “remote learning.”

In deference to COVID, schools must now find ways to pay for more technological resources, as well as enhanced on-campus anti-viral and public health measures. A problem that will no doubt be compounded by the fact that, due to the pandemic, California is potentially facing a $54 billion deficit. Which will mean cuts to public education, which as of March 13, received about 40 percent of the state’s budget.

While the question about future school funding can’t be overemphasized, it is by no means the only question about remote learning demanding to be answered. Such as:

• Does remote learning really work?

• Can it actually replace in-person classroom instruction?

• What does research say about the efficacy of remote learning and its impact on students?

Harvard University’s 52-year-old education research program, Project Zero, which works with schools, museums, businesses, and organizations across the world, aims to answer these questions by exploring issues of understanding, thinking, creativity, and the development of human potential.

“We have reached a point in the learning sciences where we recognize that learning is very much a social endeavor in which our interactions, discussions, questions, and explorations occur in the context of others,” said Ron Ritchhart, a Project Zero professor. “This is true of all age groups. Good teachers recognize this and seek to foster it whether in class or at a distance. The challenge is in our current circumstances how to do that.”

According to Ritchhart, a group of physics and statistics professors at Harvard have developed a free online platform called Perusall that helps students more easily interact with content such as textbooks, articles or papers, as well as communicate with other students, so they can more actively discuss material online.

“Some online platforms, apps, and services do this better than others,” he says. “But simple delivery of content is not what produces learning. It is the interaction with the content that matters.”

However it is still too early to know how remote learning will impact education in a post-coronavirus world, Ritchhart explained.

“Just as we don’t know how COVID-19 will affect the economy, our politics, or our long-term health, it is too early to know the effects it will have on students’ learning,” he said.

Because students have only been out of the classroom for several weeks this spring, and because the semester is less academically heavy than other semesters, Ritchhart doesn’t think the consequences of COVID-19 thus far pose a long-term risk to a child’s education.

However, if remote learning continues into next year, Ritchhart predicts much more profound and potentially negative implications for students, regardless of age.

“Can people learn online?” he asks. “Yes, certainly. The challenge for schools is how to keep children connected to each other and to their teachers. This is especially important for young learners, but it’s important to all.”

After nearly two months of full-time remote learning in place of face-to-face classroom education, local educators and others are in a position to answer some of the inevitable questions that arise from this unexpected teaching experiment.

• Are our children falling behind academically as a result of remote learning?

• Is the COVID-19 crisis simply exacerbating problems that already existed in our public education system?

• What are both public and private educators doing to make remote learning as positive an experience as possible for every student, regardless of socio-economic status or learning abilities?

• Does remote learning really work? And if so, what long-term changes can we expect for our children’s educational future?

Here is how our local educators are attempting to answer these critical questions, while also readying themselves for the “new normal.”

Change is Now

In 2005, Rob Hereford was the head of upper school at a private campus in New Orleans when Hurricane Katrina hit.

“We evacuated to Houston,” he recalls. “We didn’t have Zoom or anything like that back then. Even texting was a new thing, and there was just no online platform for learning whatsoever.”

It took Hereford and his colleagues three weeks to come up with a solution.

“Until then, the kids had nothing,” he said.

On March 11, 2020, Hereford, now head of school of Montecito’s Laguna Blanca School, held a meeting with Laguna Blanca’s advisory board. He told its members that, while all schools were likely to shut down any day, he hoped that because of the prestigious private school’s relatively small student population – just 350 kids – Laguna Blanca might at least remain open until the following Friday.

“I thought we could get through seven days of school,” Hereford recalls. “But everything changed so much over the weekend. Suddenly, we were closing on Monday.”

“We do home visits. We had a family with a broken screen, and we fixed the screen. We are making sure we follow up with every kid. We have not only one hundred percent attendance, we have one hundred percent work completion.”

– Amy Alzina, Principal and Superintendent, Cold Spring School

Because Laguna Blanca teaches students from early kindergarten all the way to 12th grade on two separate campuses, the school faced some unique challenges.

“Developmentally, it hit us in different ways,” Hereford says. “Kids at the youngest level up to fourth grade really require so much more of a family commitment to this remote-learning exercise.”

As the parent of a fourth-grader, Hereford has learned firsthand how challenging it is for parents of young children to pivot essentially overnight to remote, computer-assisted learning.

“It’s a huge learning curve for both parents and teachers,” he said. “Now, several weeks in, we’ve gotten a decent routine, and while it’s still demanding of parents, our students and teachers have figured out how to make this work as well as we can.”

For middle school students attending Laguna Blanca, Hereford continued, teachers and administrators quickly realized that the daily schedule of classes was simply too long to be effective.

“What we realized we were doing was gluing kids to their screens for eight hours a day and on top of that having them do homework, which was largely onscreen as well,” Hereford said.

In response the school limited class time to three hours a day, leaving afternoons open for students to either get help with classwork or homework or simply go outside and get some exercise or fresh air.

Upper school students included a lot of anxious juniors and their parents worried about college applications, as well as seniors who missed being around each other and felt like they were missing out on being able to celebrate their graduation around actual people.

“All that is gone now,” says Hereford. “We can try to recreate it in Zoom meetings, but it’s not the same as face-to-face, and frankly it’s exhausting to do.”

Hereford hopes that weather might help allow Laguna Blanca to re-open next fall, despite whatever social-distancing guidelines are still in place.

“One of the great things is we can move class outside,” he explains. “Ninety-five percent of days when the weather is good, we can move out into the quad or the field. We only have eighty kids in the lower campus and can try to spread them out.”

Yet Hereford admits he still has no idea what next year will look like.

“I’ve got a running list of questions I have to answer before we open school,” he says. “And that list is growing.”

Although his intention is to reopen as soon as possible, Hereford is prepared for the possibility that remote learning will continue after the summer.

“It’s possible we will be in and out of this remote-learning model next year depending on how testing goes,” he says. “We will need to be ready to flip a switch.”

Outdoor No More

Unlike other local schools struggling with how to adapt to remote learning, the Santa Barbara Middle School (SBMS) has a unique challenge because its curriculum leans so heavily on outdoor group activities, especially for graduating 9th graders. That’s not a typo: SBMS is one of the few remaining middle schools that prepare matriculating students for sophomore year of high school by providing them with a rigorous outdoor education program which lasts three weeks and includes surfing, kayaking, biking, and climbing mountains.

“We keep our ninth graders so they leave the school with some leadership experience,” says Brian McWilliams, head of school, who also teaches World History to 9th graders. “We don’t farm it out but do it all internally,” he says. “Eighty to ninety percent of the faculty does this, including me.”

The school’s major outdoor event each year is the so-called Rite of the Wheels, which involves a long-distance bike trek, whether in the Pacific Northwest, Marin County, or in the Arizona desert. Needless to say, neither that expedition nor the rest of the school’s outdoor curriculum is happening this year. “Thank god we at least had the beginning of the school year,” McWiliams says, “but we really miss this opportunity.”

Although the school has stuck with the letter grade system, it has relaxed the curriculum to three one-hour classes per day so as not to exhaust students with screen time. “It’s working out pretty well,” says McWilliams. “We have academics but also fun, goofy things,” like the school’s celebrated Carpe Diem Bucket List. “The whole theme of the school is carpe diem,” he adds. “We encourage our kids to go outside and do something, whatever it is. It’s on them to select something.”

According to McWilliams, remote learning must be equally effective for both well-endowed private schools and budget-challenged public schools. “Seventy percent of our kids go on to public schools, so we have to make this work for public schools, too,” he argues. “You should be able to get good writing, reading, and discussion without this arms race of homework. The question we need to ask ourselves is how do we light these kids up, even if it’s through a darn computer.”

Despite the loss of the school’s outdoor learning program, McWilliams says he feels lucky compared to other local educators. “Where we are lucky is we are small and can be nimble and flexible,” he explains. “We expect to start on campus next year and have a regular program, but we might scale back some of our trips, and maybe delay our full-contact sports until we know more. But we are small and we can close campus for a week and get everyone tested and do contact tracing and get back in the classroom more quickly than larger schools. There are a lot of silver linings here,” McWilliams concludes. “I almost feel guilty because some people are really hurting. Even though one-third of our kids are on financial aid, we are so lucky compared to just about everybody.”

Time Zones Matter

Founded in 1910, Carpinteria’s exclusive Cate School has just 292 students, about 80 percent of whom board on campus throughout the school year. Although the school’s average class size is tiny, the student population, which hails from 19 different countries and no less than 30 states around the country, couldn’t be more diverse.

While the COVID-19 outbreak came suddenly, according to Charlotte Brownlee, Cate School’s director of admissions and enrollment, the timing couldn’t have been better.

“Our Spring Break was earlier than a lot of other schools,” Brownlee said. “We sent kids home on February 27 for a two-week break. Late in the first week, we realized that we may not be able to bring our kids back.”

According to Brownlee, Cate used the extra vacation week to come up with a remote learning plan that would be ready to implement within days. One of the first things the school realized was how challenging it would be to simultaneously pull together students from all over the world into an online classroom.

“Time zones are definitely our biggest challenge,” says Brownlee. “We have kids in twelve different time zones from Africa and Asia to Alaska, just all over the place.”

To accommodate as many students as possible, Cate has rescheduled certain classes for the evenings so that students halfway around the globe can participate.

“We have kids from a variety of economic backgrounds, so we also helped some kids get access to Wi-Fi,” adds Brownlee. “By and large we have the kids hooked into our program.”

Because Cate is only for students between 9th and 12th grades, it doesn’t face the same remote learning challenges that schools with younger students must grapple with.

“We are lucky because high school kids can be independent learners,” Brownlee says.

Juniors recently participated in a Zoom-based college application exercise where each student was handed four college applications with the task of accepting one application, denying another, and wait-listing the remaining two.

“We had two actual college admissions officers on the Zoom call with them and they walked all the kids through how they would have done it,” she says.

Brownlee is optimistic that Cate will be able to return to a normal school year this fall.

“Obviously our primary goal is the health and well-being of our students and faculty,” she says. “But the next most important goal is to determine how we can accomplish as much learning as possible, and face-to-face learning is still the best way to do that. Of course, we hope to reopen, but we’re looking at a variety of scenarios.”

Small Scale Success

Like the nearby Montecito Union School, Cold Spring School is a one-school district located in an extremely wealthy demographic area. And with just 169 students, it has the added benefit of being small. “One of the benefits of being a small school district is that we were able to easily pivot over the weekend,” says Amy Alzina, Cold Spring’s principal and superintendent. “Some schools lost as much as a week or a month, but we were able to move in a much more efficient way.”

It didn’t hurt that Cold Spring had already begun gradually investing in technology. “When I came to Cold Spring, the technology was outdated,” Alzina says, adding that she worked with the school’s educational foundation to create a lease-to-own program that funded half the cost of each student’s electronical device.

As a principal of a small school, Alzina is intimately involved in the new, remote-learning based curriculum. “All the students Zoom on to me at 8:25 am, so I can keep everyone accountable,” she explains. “We sing happy birthday to kids, highlight students, and I do a fun, ‘80s-style workout. This is where I tell my colleagues to ditch the tie and have fun. You are a cheerleader, you can have fun, and success builds success.”

Creating a fun yet structured online routine is the key to successful remote learning for young students, argues Alzina. “After meeting with me, the kids get on Zoom with their teacher, who keeps them on until lunch. After that, our specialist teachers come in with art, drama, and other project-based learning.”

Every Friday, parents drop by to pick up packages of art supplies, worksheets, and even garden planners which include a small bag of soil and a plant. According to Alzina, Cold Spring School’s instructional assistants have helped families resolve technological issues at their homes and established Zoom chatrooms to provide further aid. “We do home visits,” she adds. “We had a family with a broken screen, and we fixed the screen. We are making sure we follow up with every kid. We have not only one hundred percent attendance, we have one hundred percent work completion.”

Beyond Zoom

Along with Cold Spring School, the Montecito Union School (MUS) is extremely fortunate to have a student body ranked among the most privileged in California, if not the United States. Because of this, MUS has an educational foundation that, among other things, has raised enough cash to send administrators and teachers to Harvard University’s Project Zero, a summer training session which provides them with the latest and most innovative educational training.

Despite all this, Anthony Ranii, MUS’s principal and superintendent, says he never imagined Zoom being used as an educational tool. Besides video chats with contractors and architects, he had never utilized video conferencing software in his professional life. But in the hours and days after California’s schools were ordered to close, Ranii moved quickly to create a Zoom-based remote-learning curriculum. “It was not unknown,” he says of the software, “but we had never thought of the whole concept of using it for instruction.”

In the meantime, Rannii sent parents a guide to online educational resources to help them keep kids on track with their homework. As remote learning sank in, Ranii says the school began to adapt to what worked and what didn’t. “We have gone through three iterations thanks to feedback from staff as well as a survey that went to parents,” he says. Now, students are in Zoom classrooms from 9 am-noon, Monday through Thursday, and 9-10 am on Friday. “We pair that with independent learning,” Ranii continues. “All our kids are doing things outside of Zoom, whether it’s as simple as reading a book, working on math, and our youngest kids are using a program called See-Saw that they can upload to their class account and get comments from teachers.”

For younger children, nothing can replace face-to-face interactions in the classroom. “There is no way distance learning is going to be as effective for them as in-person learning,” Ranii says. “It’s an unreasonable expectation, because part of what you are supposed to learn in those grades is the ability to work in a group on a project together over several weeks. All those things are possible in the digital world, but for little kids, it’s a lot harder.”

The inherent challenge of providing good early childhood education via Zoom is only magnified thanks to socio-economic inequalities. “When I look at California and the nation, this pandemic is exacerbating the haves and the have-nots,” he says. “Everyone in Montecito Union School has their own device and Wi-Fi at home and parents that are computer literate and reading and writing literate and are supporting their kids amazingly well.

That said, Ranii worries about the fate of other public schools in the Santa Barbara area that aren’t so fortunate. “There are plenty of parents working low-paying jobs, and some of these kids aren’t getting what they need,” he says. “And that divide will continue to grow.”

The Grade Debate

Unlike well-funded private schools and tiny, one-school-district public schools, public schools in the city of Santa Barbara are dealing with much more severe, real-world challenges when it comes to implementing remote learning. “People always ask me what new problems we are facing,” says Elise Simmons, principal of Santa Barbara High School (SBHS). “But the problems aren’t new. The problems are the same, they’re just amplified.” Although SBHS has a well-earned reputation for community and family outreach which has helped the school create a supportive atmosphere on campus, many students come from low-income families. The school recently completed a survey to determine how many kids lacked either a computer or iPad at home or had no reliable Wi-Fi access.

“We found that it was less than one hundred students,” she says. “But that’s still five percent of our population, and who knows how many more kids will lose that access by the next week?”

For the past eight years, students and teachers have increasingly relied on technology in the classroom. “So our staff already knows how to use Neo, a learning management system that allows for distance learning, and this experience is helping us a lot now. At first we wanted to take advantage of the COVID-19 crisis to have more students learning about it in class,” she recalls. “But then we got feedback from students saying, ‘Please don’t talk about COVID anymore, anything but that!'”

According to Simmons, a major challenge has fallen on teachers, who had little time to prepare for remote learning as a full-time teaching concept. Their solution was to ask students for their feedback and incorporate that discussion into a more flexible, learn-as-you-go curriculum. “We are now in a new space where learning is new for everyone,” says Simmons. “I am proud of our teachers for asking for that feedback. It’s awesome to see, but it’s exhausting for the staff; I can see it in their faces.”

At press time, Simmons and other public school administrators throughout the county – a group colloquially known as “The Cabinet” – were still busy working out various plans for how schools might reopen next year. “There are multiple scenarios and they are ever-changing,” she explains. “Do we reopen as usual, if the virus is gone and we are all safe? Do we reopen with remote learning like where we are now? Or is there something in between where we are able to explore ways to have less students in the space, possibly a different bell schedule?”

Another big debate: Whether or not to award letter grades this semester or simply implement a pass/fail system. After hearing from college admissions officials who said that they weren’t going to judge students for having poor grades this semester, Simmons argued that the school district should ditch letter grades. But after worried parents, primarily of high school juniors, demanded letter grades, the county ultimately approved a compromise measure allowing willing students to opt to receive letter grades for the spring semester.

Whatever grading system is used, Simmons says her job is to ensure that remote learning doesn’t negatively impact the all-important connection between teacher and student. “It’s a time of innovation,” she says. “But how we are delivering instruction to the kids is the crux of it all. You present a problem or question to them and give some guidance and students can take it in the direction they’re interested in. Let them figure it out on their own.”

Uncharted Waters

With 21 schools and 15,000 students, the Santa Barbara Unified School District (SBUSD) is one of the oldest and largest in the state.

“Many families are really struggling,” said Laura Capps, president of SBUSD’s board. “We have kids taking care of parents who have COVID-19. This pandemic has really exacerbated all the inequalities that were there before it. Some kids have enough support, maybe even too much, and some don’t have nearly enough.”

After floating an unpopular and quickly-dropped plan to reopen schools in July, Gov. Gavin Newsom is expected to announce a revised reopening date for later this year. “It’s impossible to imagine a more fraught task than choosing an actual date for this,” Capps admitted. “As hard as it is to close schools, it’s even harder to reopen,” she remarked. “How do we get students back in the classroom safely?”

Noting that Santa Barbara’s climate allows for outdoor instruction almost year-round, Capps hopes that schools can reconvene on campus perhaps under modified rules.

“I am not forecasting that, but it adds to the possibilities we have,” she said. “These are uncharted waters and if there are good ideas we want to hear them. This is definitely a learning opportunity and now is the time.”

Susan Salcido, Santa Barbara County Superintendent of Schools, has already convened a team to examine options for reopening schools in the fall, but no specific date has yet been set. The priority, insists Salcido, is serving students in the most compassionate, effective, and supportive way.

“Not only did we want to educate students, but we were also thinking deeply about the need for food continuity, creating and maintaining social and emotional connections and serving our students with unique abilities,” she said.

“School district technology teams have distributed devices to students with help from organizations like Partners in Education, which has a ‘computers for families’ program,” Salcido adds.

So far, 207 refurbished computers have been distributed to Santa Barbara area families at no cost.

Meanwhile, because colleges and universities have pledged that their acceptance policies would reflect an understanding of the challenges faced by applicants, Salcido is confident that students won’t be punished for their COVID-19-era grades or lack thereof, should they opt for the pass/fail credit.

“This allowed districts to make grading decisions for their student populations based on the ages and grades served,” she said. “It’s just one example of the weighty and challenging decisions that districts have had to make during this extraordinary time.”

“This is an unprecedented time in our world and in our schools,” Salcido continued. “There is no playbook on how to pivot all schools to remote learning in a pandemic. However, the lessons we learned during the Thomas Fire and January 9 debris flow helped prepare us to transition quickly and thoughtfully, working collaboratively and creatively as a group of twenty school districts.”