An Unexpected Discovery

The life and accomplishments of one of the most influential but least known Santa Barbara architects will be celebrated at the Lobero Theatre on January 5. LUTAH A Passion for Architecture: A Life of Design tells the story of Lutah Maria Riggs (1896-1984), a protégé of famed architect George Washington Smith, who, among other landmark local buildings such as the Vedanta Temple, designed the Lobero itself. The film premiered at the theater in 2014 before screening at film festivals around the world and is now returning home for a special screening followed by a panel discussion.

The documentary is the brainchild of Gretchen Lieff, a former Bay Area radio journalist turned winemaker. After getting her start in Napa Valley, Lieff and her husband moved south 15 years ago to open Lieff Wines at Lieff Alamo Creek Ranch in southern San Luis Obispo County. She got the idea for the film after purchasing Los Suenos, a Montecito mansion designed and built by Smith in 1929. At first, Lieff wasn’t wild about the five-bedroom, eight-bath, 10,000 square foot house located on more than three acres of land. “I wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about moving in,” she admits. “But slowly over time, I began to appreciate the house more and more, and ultimately very much.”

As the house gradually grew on her, Lieff began to invite neighbors and friends to soirées at Los Suenos, where guests would drink wine and stroll through the garden. One time, Lieff offered a tour of the house to Bob Easton, a local architect who was working with the George Washington Smith society, a group of Montecito residents who owned Smith homes. “I had been in the house before but had never been in the master bath,” Easton recalls. “There was a really flamboyant mosaic and it was unlike anything Smith ever did, but Riggs could really draw, and I said, ‘This is a floor by Lutah.’”

Lieff didn’t recognize the name. “I said, Lutah who?” she recalls, laughing. “And then I started doing research on Lutah and realized how fascinating she was.” For help, Lieff turned to Melinda Gandara, the research archivist at the Architectural and Design Collection at the University of California Santa Barbara, who had access to an entire room full of material belonging to Riggs.

“I was the archivist who organized Lutah’s papers,” Gandara affirms. “I was in a room with one hundred boxes and it took me over nine months. I knew of her but never got to see her work until I saw her papers; they are extraordinary. She was a collector and kept everything, including records of her parents’ letters and locks of hair, ephemera, drawings, postcard slides… I would meticulously go through them, create a finding aid and work through the drawings to find the materials attached to the buildings.”

Gandara quickly realized how talented Riggs was as an artist and how closely she collaborated with George Washington Smith; chiefly by doing the preliminary drawings or add-on renderings for many of his most famous projects. “You will see her hand in everything,” Gandara says. “At Casa Del Herrero they wanted a library, so she designed it.” The library in question is a cozy tower almost hidden from the rest of the house at the end of a hallway, a bookworm’s dream cave.

As she built her business, Riggs often took over Smith’s remodel jobs. “While she owed her career to Smith, in my opinion he needed her in ways that changed his practice, because he didn’t have her draftsman skill,” Gandara reasons. “Had she not been an architect she could have easily been an artist.”

Gandara delved deeper into the files, becoming increasingly fascinated with Riggs, who was clearly not someone who yearned for the spotlight. Born in Toledo, Ohio in 1896, Riggs grew up in circumstances that could charitably be described as modest; her physician father left the family and then died when she was a young child. Following high school in Indiana, Riggs moved with her mother to join her wayward stepfather in Santa Barbara, where she attended community college before winning a scholarship to UC Berkeley.

After obtaining her undergraduate degree in 1919, she began her graduate studies in design. In 1921, when her mother fell ill, Riggs abandoned the program and returned to Santa Barbara. The timing proved fortuitous; Riggs managed to win a week-long trial period working as a conceptual draft artist for Smith. From Monday through Saturday, Riggs drew up her plans while standing over a desk. She was still standing on her feet at the end of the sixth day, when Smith slyly informed her that she now had a job. “You will have a stool on Monday,” he promised.

An Architectural Pioneer

Talent and creative vision created a bond between Riggs and Smith, who treated her like a daughter, and who brought her along with his wife, Mary Catherine Greenough, for a two-year-long artistic tour of Mexico in the early 1920s. “They were going to look at producing a book on Mexican architecture,” Gandara explains, “but the book was never produced because his commissions were taking off.” Fortunately, this meant that, for the better part of a decade, Riggs was hard at work collaborating with Smith on some of Santa Barbara’s most iconic homes and architectural projects.

“I met with her and knew who she was, because she was a friend of my parents,” recalls Kellam de Forest, the famed Hollywood visionary and research consultant of Star Trek fame whose father, Lockwood de Forest, was a landscape architect who occasionally worked with Riggs. “My father designed the gardens for a number of the houses she worked on. People who draw up plans and have Lutah design the thing and would she would recommend my father or vice versa.”

When his father died rather suddenly in 1949, de Forest says, his mother arranged for Riggs to take over some of his outstanding projects, including the completion of the landscape design work for the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. “She wasn’t terribly social and certainly was not in my parents’ circle of friends, but she was highly regarded by my parents,” he recalls. “I have no idea why she kept a low profile but certainly people knew who she was, and she was a person to turn to. If you wanted an architect to design something in Santa Barbara or had a project, you would get Lutah to do it.”

De Forest credits Lieff with finally giving Riggs the attention she deserves as an artist. “I’ve seen the film,” he says. “It’s excellent. I think her contribution to the architecture of Santa Barbara is underestimated, but I am glad more people are getting another chance to see it. I’m glad it’s coming back.”

Famed Santa Barbara architect and George Washington Smith expert Marc Appleton believes that the close partnership between Riggs and Smith brought out the best of both architects. “I’ve always felt, when you look at her career, that she was never as good on her own as she was when she worked with George Washington Smith,” Appleton argues. However, Appleton quickly adds, “I would say the same about Smith – that he was never as good as when he worked with Lutah Riggs. I think the best work either of them ever did, they did together.”

Appleton admires Riggs for being a pioneer in what continues to remain a male-dominated profession. “She was a woman architect of record in an era when female architects were few and far between and were up against a lot on this misogynistic business that we work in,” he says.

That aside, Riggs stands out among her peers for her natural born talents as an artist. “In my view it was her drawings that were so important,” Appleton argues. “George Washington Smith used her drawings all of the time. It wasn’t that she wasn’t an accomplished architect, but for me, her most lasting contribution was her drawings. Even today, in my office, we often reference Lutah’s drawings in our own work on Spanish Colonial projects.”

When Smith died suddenly in 1930 of a major heart attack, Riggs quietly took over his practice. “She was never a self-promoter,” Gandara argues. Unlike Julia Morgan, who designed Hearst Castle, Lutah never became famous as a female architect during her lifetime. “Lutah just wanted her work to stand alone and she never looked at herself as a female architect,” Gandara continues. “She knew Julia Morgan and wrote her, but they never connected.”

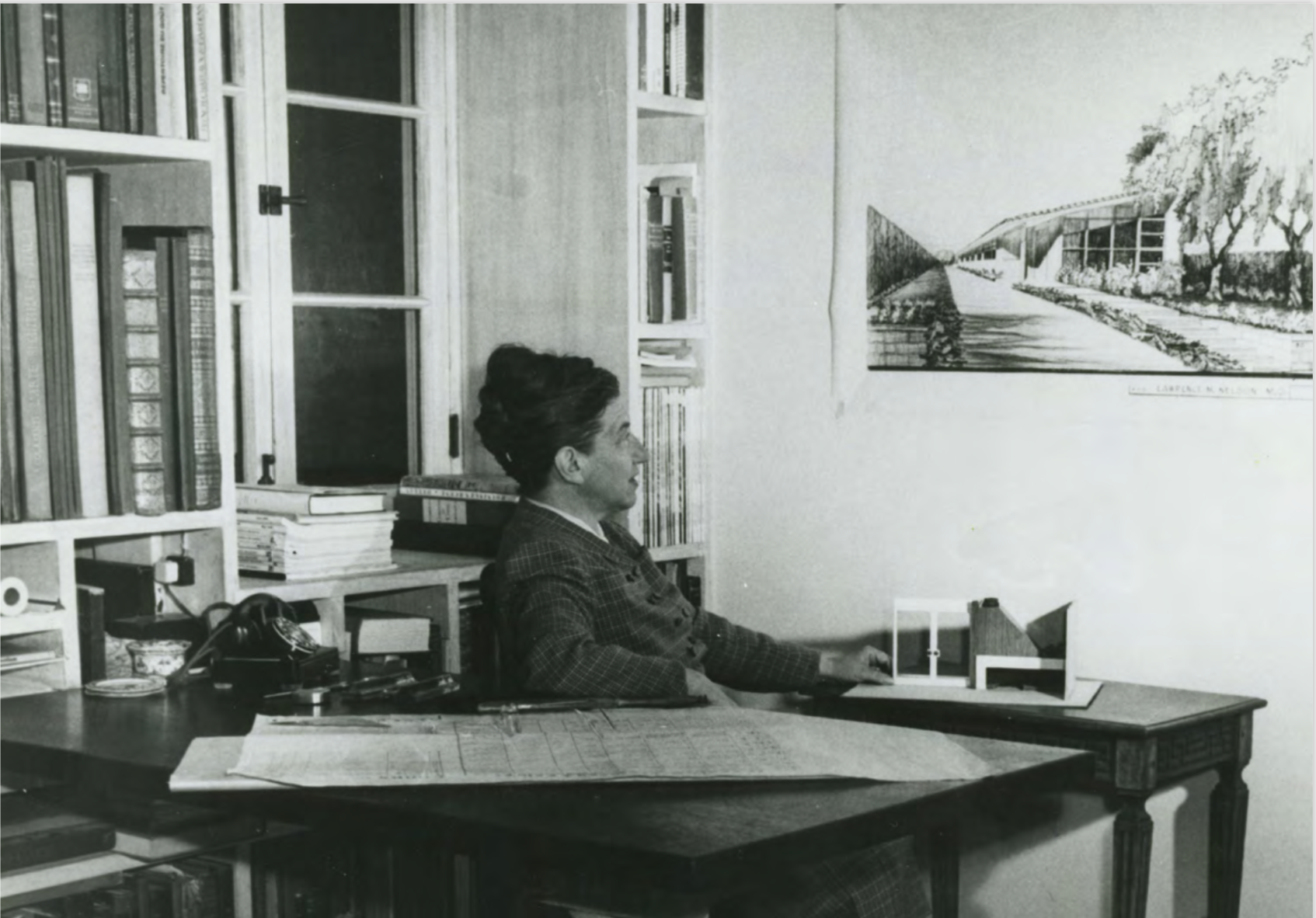

Even at the peak of her career, according to Gandara, Riggs worked out of a one-person office with no employees or assistants to handle the rote work of ordering, invoicing, and billing. “She did everything, wrote the letters to the client, did all the drawings, was on site, and she did this with no self-aggrandizement; she wasn’t looking to be noticed,” Gandara says. “In many ways she didn’t want to be seen. She wanted her work to shine. She wasn’t afraid of drawing over and over again. She drew a fireplace twenty times for a single person home in Isla Vista – the Francis Coleville house.”

Perhaps Riggs’ crowning achievement is the Vedanta Temple, which she built in the mid-1950s. “She did an amazing passive ventilation system, drawing air out of the bottom going out the top so it was able to work acoustically,” Gandara explains. “She understood how sound moved on this beautiful arched ceiling. You can hear people whispering.” De Forest agrees. “I think the Vedanta Temple is her best work,” he says. “It works so well. It is designed such that it fits with the area and it’s such a unique building.”

According to Gandara, Riggs insisted on personalizing each home for the people who would be living in it, often by repeatedly interviewing her clients, especially the future woman of the house. “She would ask people, ‘Where do you eat breakfast? Where does the sun set on the property?’ and incorporate that [information] into the design, Gandara explains. “Most architects when they do a project and the project is done, the file is completed. But her files are accordion files because after the project was completed, if there was a wedding or death of an owner, or the house was sold, that went in the file. She was connected to every house she made.”

Lutah Hits the Big Screen

Not long after being approached by Lieff for help with researching Riggs, Gandara began participating in Lieff’s weekend soirée group, which soon morphed into a planning committee for a documentary about the beloved architect – and the parties began to grow from there. “Ten people went to twenty; twenty went to thirty; thirty went to forty and in four to five months people were asking what can we do to share her story,” Gandara recalls. “I said probably a documentary, so we pulled all this material together and we raised over $100,000 in less than six months and it allowed us to move from a thirty-minute documentary to a sixty-minute documentary.”

After contacting the various current owners of all the local homes built by Riggs, Gandara says the crew was able to win permission in every home except the architect’s residence and one other house. “I have never worked on a project where we got that access,” Gandara marvels. Meanwhile, Lieff created a non-profit called the Lutah Maria Riggs Society to help fund the production of the film, which was completed in less than nine months before being submitted and accepted for the Santa Barbara International Film Festival in January 2015.

From there, the documentary travelled around the country, hitting 13 film festivals in California alone; it also screened at another 12 festivals in the United States for a grand total of 53 events and nine awards worldwide. “It was wonderful,” says Robert Adams, a member of the Lutah Board of Directors who worked as the documentary’s film festival marketing coordinator. “It made us feel we had a story to share outside of Santa Barbara. People were able to relate to a female figure breaking through a bunch of barriers in the architectural profession, having started in humble beginnings and rising to the top of her field.”

For Lieff, seeing the film’s success beyond the confines of Santa Barbara and knowing that Riggs has finally received the recognition she deserves is a dream come true. “I often think of Lutah, of her courage and quiet fortitude,” Lieff says. “Lutah had enormous challenges in her life, particularly as a young girl. But her grit and determination broke through. I fell in love with Lutah and ended up falling in love with my house, the subtle lighting and attention to detail. I liken the film to a love story between two women that extends through decades of time.

LUTAH A Passion for Architecture: A Life of Design screens January 5, 2020 at 8 pm at the Lobero Theatre (33 East Canon Perdido Street) followed by a panel featuring Marc Appleton and other local architectural luminaries. Tickets available at lobero.org. For more information, call (805) 963-0761. Presented by the Lutah Maria Riggs Society (lutah.org).

You must be logged in to post a comment.