Pepper Trees and Pepper Lane

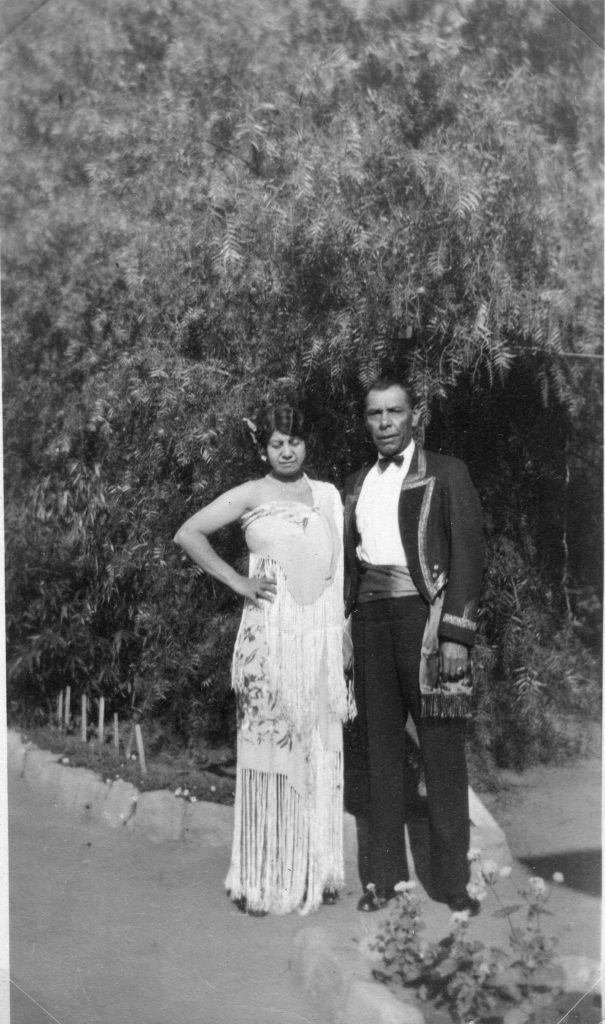

Once upon a time pepper trees reigned supreme in California, and their unique and ubiquitous presence inspired Eastern visitors to succumb to paroxysms of poetic expression. One visitor to Santa Barbara in 1874 enthused about its umbrageous and graceful foliage. Another commented on lanes of pepper trees whose wonderful feathery foliage and gorgeous scarlet berries flung a pungent spicy odor into the mist.

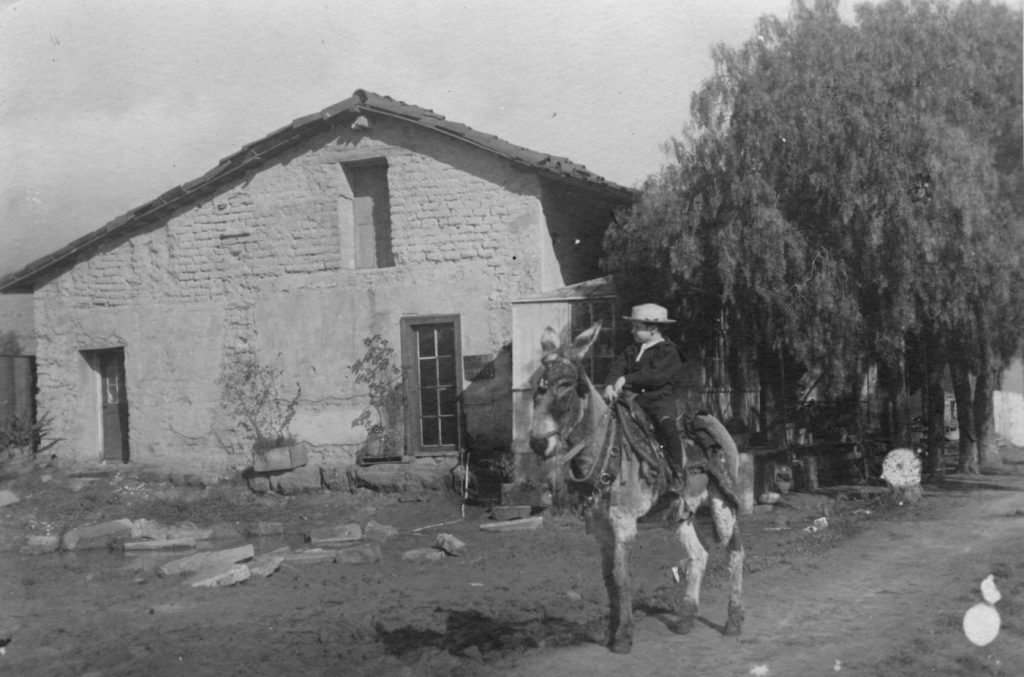

Sarah Augusta Winchester, who moved with her family from Maine in 1869, recalled her romantic arrival years later. “We arrived in Santa Barbara [on] a beautiful moonlit night, coming on the steamer and landing at the old wharf at the foot of Chapala street. We were driven up State street, which was lined with overhanging pepper trees that touched our shoulders as we drove under them.”

Local poets embraced pepper tree imagery. The graceful tree became an image in a cradle song written by Mary Bowman, who penned, “Rockaby, lullaby, the sun is descending, soft fleecy mist veils the mountain tops o’er/Rockaby, lullaby, pepper boughs bending, are swaying and swinging their bright scarlet store…”

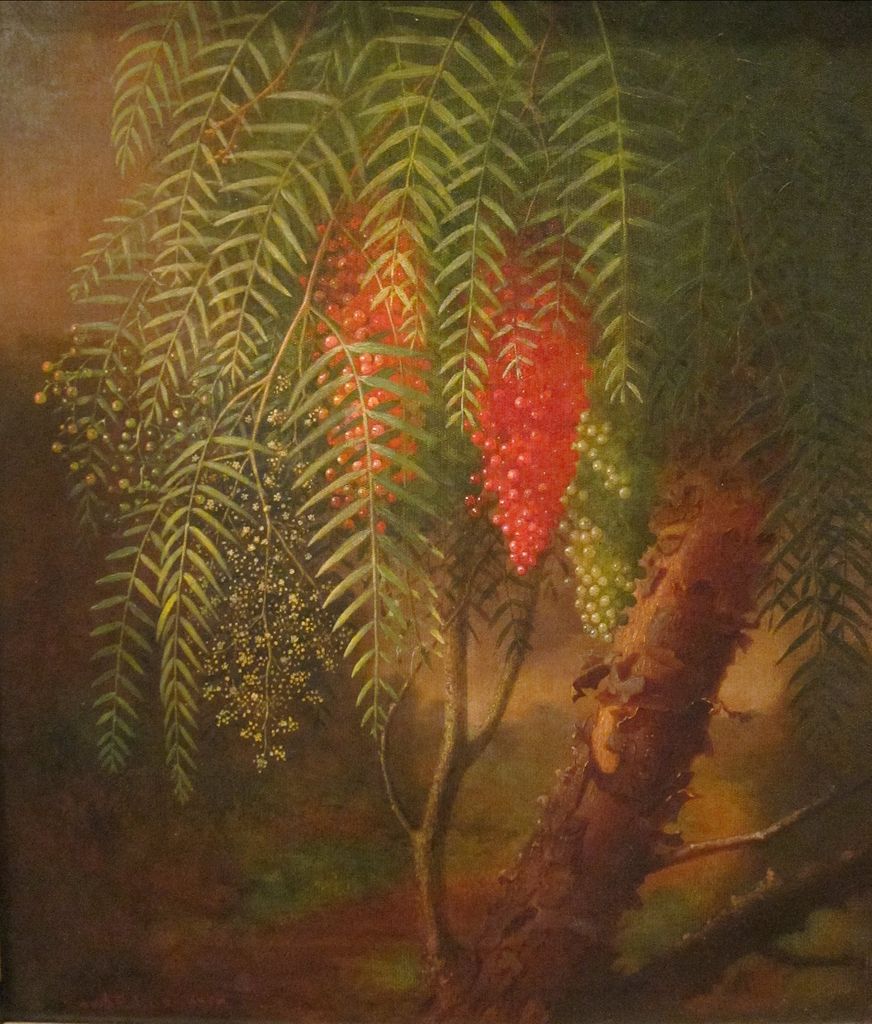

Artists became entranced by its colorful fruit. In 1883, Edward Edmonson, an artist from Dayton, Ohio, who had opened a studio in Santa Barbara, showed a painting of the delicate fronds and pendulant berries of the pepper tree. Edmonson painted several versions of this image and sold them to wealthy Easterners.

Pepper tree boughs were favored for decorations for special occasions such as the 1876 welcome soiree for artist Henry Chapman Ford and wife. The Morning Press reported that the rooms, “…were tastefully decorated with branches from the pepper tree, and hanging vines of ivy and woodbine, and brilliant bouquets, all smiling a voiceless but fragrant welcome.”

Seventeen-year-old Elizabeth Eaton Burton, who would become a well-known Arts and Crafts artisan, sojourned in Los Angeles in 1887 on her way to Santa Barbara. In her memoir she wrote, “Dust and Pepper trees, this is all I remember at first on landing in the Pueblo de Nuestra Señora, la Reina de Los Ángeles… The pepper trees were magnificent, spreading and arching their graceful fronds over the meandering roads, but their large bulbous trunks and twisted roots had preempted what little semblance of sidewalks had been started, so that you were literally forced into the dusty street.” (Even through her awe of the tree, Elizabeth saw to the root of the eventual problem with pepper trees.)

Origins

By the 1870s, pepper trees were so common in California that newcomers thought it was a native, but the California Pepper (Schinus molle) was an immigrant from the Peruvian Andes. Most historians seem to agree that the first pepper tree in California took root at Mission San Luis Rey, when Fr. Antonio Peyri planted some seeds brought by a visiting sea captain circa 1827. After El Grito de Dolores, which signaled the beginning of the War for Mexico’s independence from Spain in 1810, Spanish supply ships to the pueblos and missions became infrequent and by the end of the war, disappeared entirely. The Californios were on their own, and may have adopted the Peruvian tree as a substitute for Piper nigrum. It is, however, not a true pepper.

The tree was clearly not unknown to the Spanish colonists in other parts of the Empire, where the strong wood was used for saddles, wagon wheels, and posts, and its fruits for spice. The fruits also have antiseptic and antibacterial properties and were used in treating wounds and infections. Given that fact, when the butchers of the California Market used sprays of pepper branches from which to hang their carcasses, it may not have been entirely ornamental.

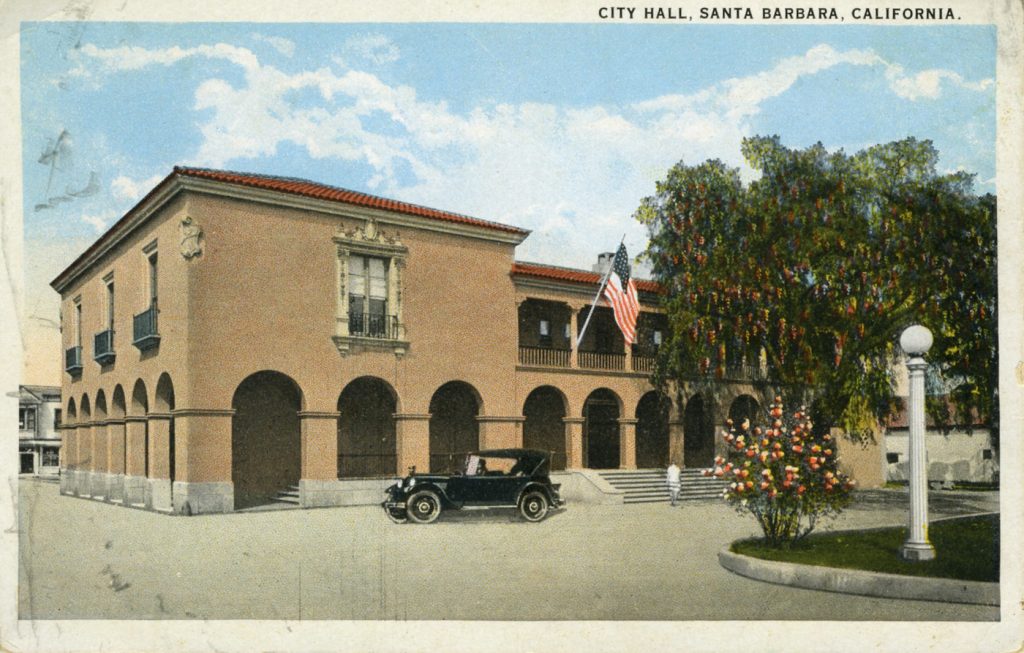

Oil from its leaves was used by the Incas for mummification purposes and the fruit for brewing an alcoholic drink called chichi. In California, however, the tree’s greatest popularity was as an ornamental and shade tree, so much so that it has become associated with California’s romantic historic past and once had a loyal following throughout the state and in Santa Barbara. In fact, the aged pepper tree that stands on De la Guerra Plaza in front of City Hall has landmark status.

Pepper Tree Controversy

In 1874, the State of California offered premiums for tree planting along roads and highways. By 1877, therefore, Santa Barbarans, who were already beautifying the fledgling town, had made lining the streets with shade trees a cause célèbre. An opinion in the Morning Press read, “There is nothing in SB that is more pleasantly attractive to strangers than the brilliant green of her pepper trees. The brightness of their emerald hues is wonderful. If State street was only lined with them, from the beach to the Arlington, what a magnificent avenue it would be! There are some giants in the lower part of town, magnificent trees, big enough to shelter a whole community, and if there were more such, it would wonderfully enhance the beauty of our city by the sea.”

More and more streets became lined with the pepper. Nevertheless, the newspaper began reporting, as early as 1877, “The roots of some of the pepper trees on State street, near Montecito street, are forcing the planks of the sidewalk out of place.” Their solution? “The planks should be cut to make room for the trees.”

In 1882, the newspaper exhorted the public to trim their pepper trees to benefit the trees and facilitate foot traffic. “Many complaints are made of the damage to clothing, hats in particular, caused by drooping boughs, which dangling low over sidewalks, besprinkle all with dust who pass.” Criticism of the pepper tree began to mount.

City Council soon passed an ordinance requiring all homeowners to trim their pepper trees and not allow them to droop on the sidewalk, and the newspapers exhorted people not to leave the debris in the middle of the street.

The Demise of the Pepper

In 1893, Dr. Francesco Franceschi and Charles Frederick Eaton established the Southern California Acclimatizing Association on Eaton’s Montecito estate. Franceschi became the leading expert on horticultural matters in Santa Barbara. In his inventory of Santa Barbara shade trees he wrote, “People here must have soon begun to look for shade and the first tree introduced for this purpose appears to have been the pepper tree (Schinus molle)… What was left of perhaps the oldest plant in town, a gnarled stump constantly pollared and abused, has disappeared quite recently from State Street in front of the Commercial hotel. Very large peppers, some of them exceedingly picturesque, are scattered about town, and chiefly in the lower part towards the ocean.”

As time passed, Franceschi saw the unsuitability of the pepper as a street tree. By the end of the century, others did, too, and a huge controversy played out in the opinion pages of the Morning Press, regarding the fate of the pepper. One writer wrote, “Before I had read many lines of Dr. Franceschi’s article on ‘City Tree Planting’ I knew that the Cocos Plumosa would jump up somewhere as a sidewalk tree as that gentleman seems to be somewhat daft on that plant, for we can not very well call it a tree.”

The writer goes on to say that he wants shade trees on the street, not ornamentals. “We can all remember how beautiful and shady were Anacapa, Arrellaga, Victoria and upper De la Vina streets with their rows of peppers before our absurd system of grading ruined them… Garden street was well-named before it was graded, being lined with peppers and acacias, but if Cocos are planted, the name had better be changed to Arizona street.”

Franceschi responded that he was not against peppers but they need to be in the right place. It was also ridiculous to think of providing shade for pedestrians in a city where everybody rides, drives, wheels, or if not, takes the cars (trams). He thinks palms from Arlington to the Mission would create an appropriate and inviting approach.

The Controversy continued for years, but buckled sidewalks, prolific debris, and the scourge of black scale caused the graceful pepper to eventually lose out to the stately palm.

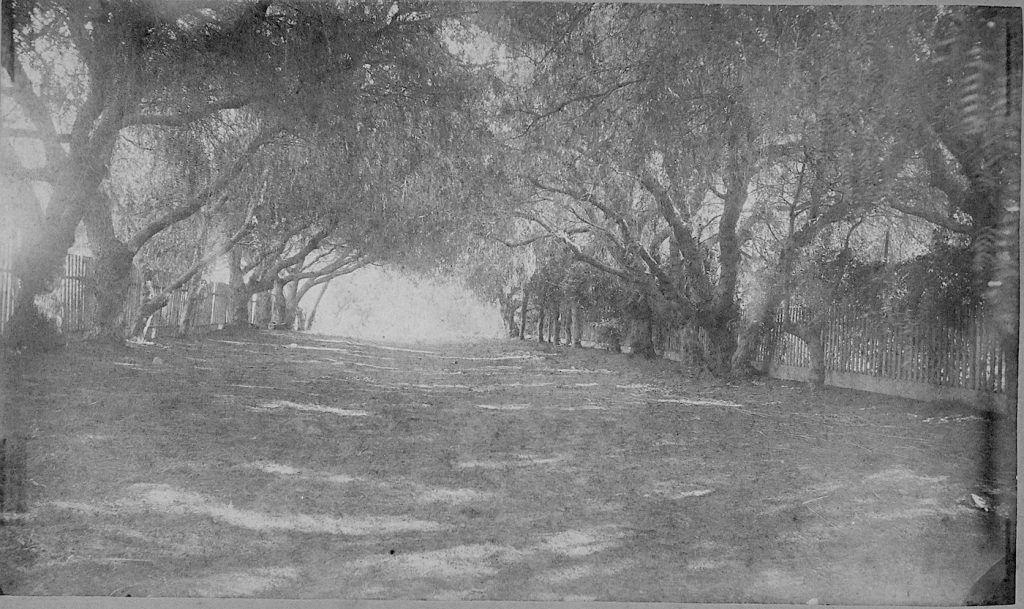

Pepper Lane in Montecito

In 1881, the dirt track that connected Sycamore Canyon with Hot Springs Road was just beginning to be planted with pepper trees. By 1898, when the time came to name the streets, the trees had grown into a shady allée. It was a surprise to many, then, when on October 4, 1909, the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors decreed the road “vacated and abandoned.” William Oothout and other residents had petitioned for the abandonment, and, there being no opposition, the Board complied.

On October 6, the Morning Press reported, “The innocent announcement in the morning paper that the supervisors had closed Pepper lane was the signal for more than one peppery conversation over the telephone by residents of El Montecito who had not been informed of the request and considered the action a land grab on the part of Oothout and his supporters.”

The petitioners for closure said the reason for the closure was that the road was little traveled and nearly impassable and required large sums of money to put into a safe condition. Louis F. Swift and Anne R. Faulkner, owners of property abutting on Pepper Lane, alleged that the closure would damage their property and asked the Supervisors for a writ of review.

This battle continued into 1912, when Helen R. Oothout deeded a 20-foot strip to the county to meet the requirement for sustainment of the road, and the supervisors declared it once more a public highway, supposedly, for “all time.” Nevertheless, its highway status was not to last. Pepper Lane, seemingly devoid of all namesake trees, is a private lane today.

(Sources: San Bernadino County Sentinel, posted 3 May 2016 by Venturi; “When Pepper Trees Shaded the ‘Sunny Southland’” by Nathan Masters; “Santa Barbara Exotic Flora” by Francesco Franceschi, 1895; contemporary news articles, ancestry.com)

You must be logged in to post a comment.