Tajiguas Moves into the Twentieth Century

Once inhabited by the native Chumash, the lands of Tajiguas Ranch on the Gaviota Coast became part of the Spanish and then Mexican land grant known as Nuestra Señora del Refugio. The Tajiguas portion was sold in 1870 to Amasa L. Lincoln and Francis C. Young, who attempted to make a living off of its lands but gave up in 1884. The next owner, Lawrence W. More, saw the ranch into the new century. (For previous article on the earlier years of Tajiguas, see Montecito Journal #25_20.)

The Mores

The six sons of the Peter Alexander More family of Ohio migrated to California where they became land speculators and ranch barons. Three of the brothers formed a partnership circa 1851 and drove cattle from Southern California to the gold mines of the north. With the profits from that business, they began buying entire Mexican land grants, the first being the Sespe grant in 1852. Over time, they also purchased many other parcels of land, including Santa Rosa Island, Rancho Lompoc and a quarter interest in Santa Cruz Island.

One brother, Lawrence W. More, and his family came to California in 1872 and took up the family business of land speculation and farming. By 1878, he was leasing El Rincon, a 2,000-acre parcel of the Dos Pueblos Rancho, and was raising barley. He had obtained the lease from Charles Enoch Huse, the trustee of the Den estate. Meanwhile, More was also buying and selling town lots and even deeded part of city block #189 to his wife, Lizzie. The notice of the transaction in the Morning Press said he had deeded it “with love and affection.”

A problem with More’s lease arose in 1883 when the heirs of the Den estate came of age and demanded both revenue from the estate and the appointment of a receiver. More was told to vacate the premises but refused because he had valuable crops in the field. The Sheriff was already mounted and ready to carry out the eviction order, when word came that the Dens had relented. More could remain long enough to harvest his crop but the crop had to be turned over to the Receiver and More had to vacate the ranch at that time.

Now landless, More was in the market for a ranch, and in February 1884 he purchased Tajiguas from the Young brothers. In October, a friend of Lawrence wrote to the local paper and described the new ranch as an idyllic place where the waters of the arroyo never failed to reach the sea and sycamore and oak trees shaded his flock. More’s cattle drank from pure springs and grazed on rolling green hills that afforded magnificent views of the Pacific Ocean, he claimed.

More now owned the historic old olive orchard and vineyard, which had, in earlier days, supplied wine for Mission Santa Ynez. Wildlife, like quail and trout, were plentiful, as were, unfortunately, mountain lions and bears that roamed the three canyons of the rancho.

The Tajiguas ranch house, vineyard and orchard were protected by an 8-foot high fence of chaparral, but there were no boundary fences so cattle and sheep strayed onto neighboring property. Coastal steamers called at Gaviota weekly and brought supplies and picked up farm products and sheep, cattle and horses from the ranches, so More had a choice of More’s landing in Goleta or driving his cattle to Gaviota.

More’s friend also reported that the Chinese cook made the most incredible biscuits and corn cakes that dripped with butter and wild honey and were accompanied by lemonade made from Tajiguas lemons. When in residence, More ate with his staff, which helped care for his horses and cattle. Lawrence and his wife Lizzie also had a Queen Anne style house in town and spent much of their time there. (It still stands today at 422 West De la Guerra Street.)

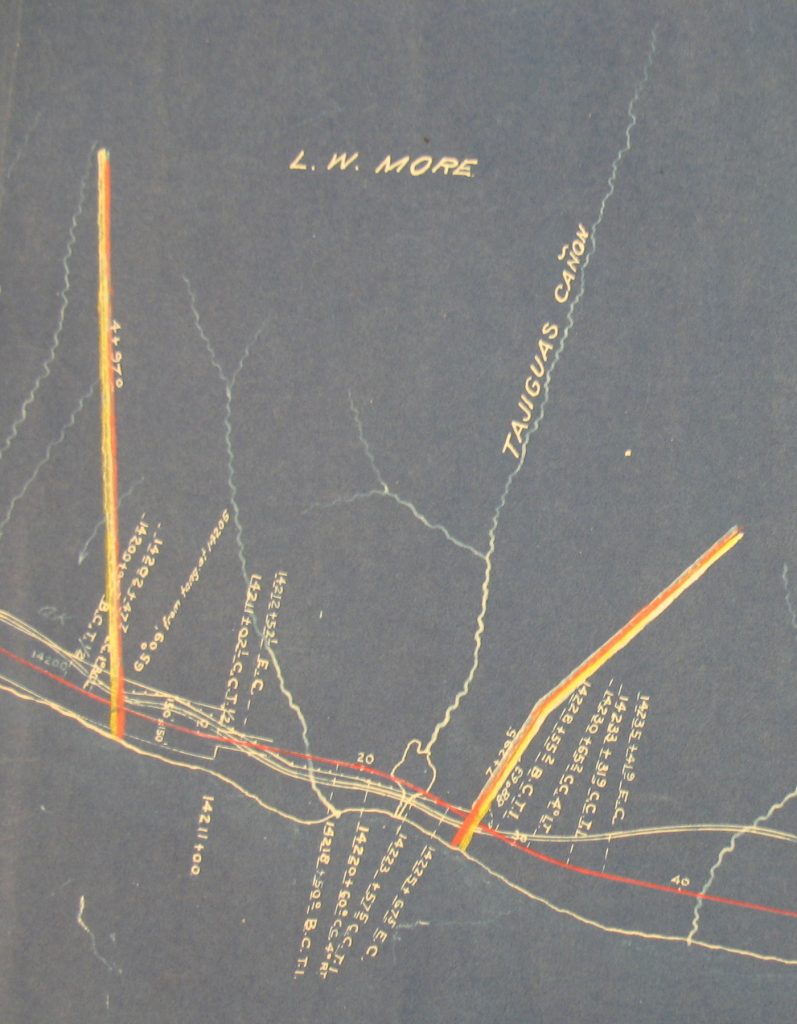

In 1887, the railroad from Los Angeles reached Elwood Cooper’s rancho, but it would be 13 more years before it was connected to San Francisco. Nevertheless, plans to do so were in the works as early as 1891 with ranch owners on the Gaviota coast being asked to grant a right of way for the tracks. More held out until the Southern Pacific Railroad agreed to place a rail station on his property.

More died in 1893 and his son, Harland Clifford More, took over ownership and management of the ranch. He added telephone service by connecting to the new trunk line through Refugio Canyon in 1903. And he joined the complaints of his neighbors when the consequence of having pushed the county road inland to accommodate the new rail line forced the road to take on a tortuous snakelike route into and out of steep ravines and resulted in clogged culverts and endangered bridges.

By 1911, the State of California was developing plans to build a 16-foot wide concrete highway through Santa Barbara County as part of the second state highway system (today’s Highway 101). Once again, landowners needed to give right of way for the new, straighter route of the coast highway and to build fences to keep their stock off of it. They were compensated for both.

In 1923, H. Clifford More decided to sell Tajiguas, and a new era began when the humble adobe home was transformed into a hacienda of the imagination as a new owner revamped the venerable rancho.

The Kirk B. Johnsons

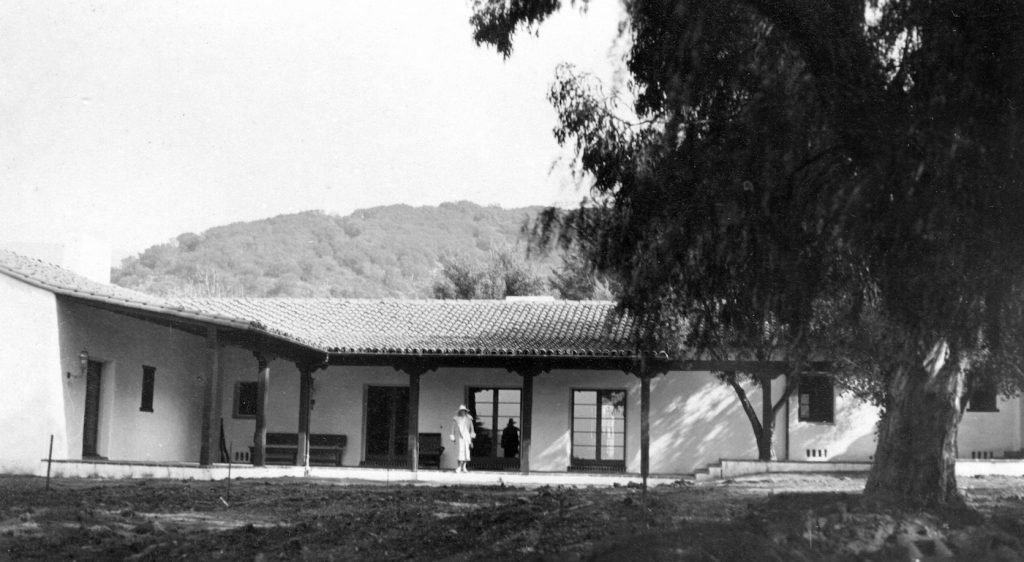

Frequent visitors to Santa Barbara, Kirk B. Johnson, and his wife, Genevieve Joyce Johnson, bought the Tajiguas Ranch in February 1924. Kirk had been a banker in New York and after his 1917 marriage to Genevieve, an heiress to the Gillette Safety Razor Company, established the First National Bank of Beverly Hills. The Johnsons had considerable plans for the historic rancho. They wanted to incorporate the old adobe into a grand hacienda and hired George Washington Smith to design it. They also planned improvements that would make Tajiguas the ideal ranch for raising purebred cattle.

As Smith went to work on the creation of a romantic hacienda (the likes of which few aged California adobes had ever resembled), he discovered that the walls and foundations of the old Ortega adobe could not carry the load of the new structure. It was decided to tear down the old adobe brick by brick and salvage those that were still viable. Under the sill of the dining room, they found a tin box with a letter from Jean McLeod Young, Frank C. Young’s wife. The date was 1872, the date of an addition to the old building. There were also two daguerreotypes of the original adobe.

Another letter in the box said, “On this 27th day of September, we the undersigned, present residents of Tajiguas, make the following statements: that the cornerstone of this building was laid at 6 o’clock Friday morning, September 17, 1872. The candidates for the presidency for this year: U.S. Grant and H. Greeley. The Pacific Mail S.S. Company have entire control of the Pacific. Santa Barbara is becoming a resort for invalids and land is held at high rates, averaging 100 dollars per acre, near town.”

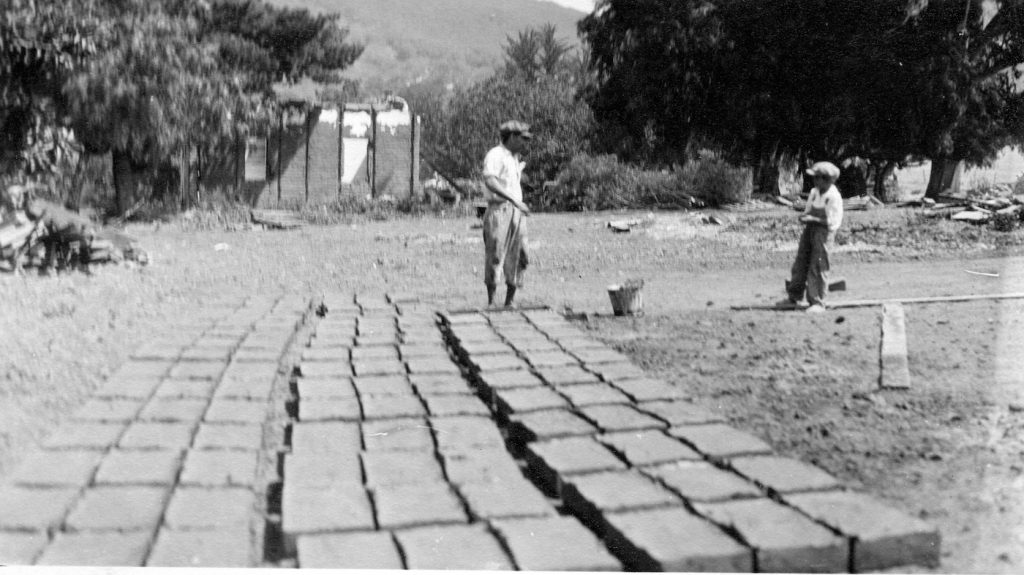

These letters, coins, and newspapers were sealed in a new box and put back into the walls of the new house when it was built. A few old bricks were saved and incorporated into the new building, and those carrying inscriptions were imbedded in the wall of a room that became Mr. Johnson’s study. George Washington Smith proceeded to pour strong concrete foundations, but also directed the creation of real adobe bricks for the entire hacienda.

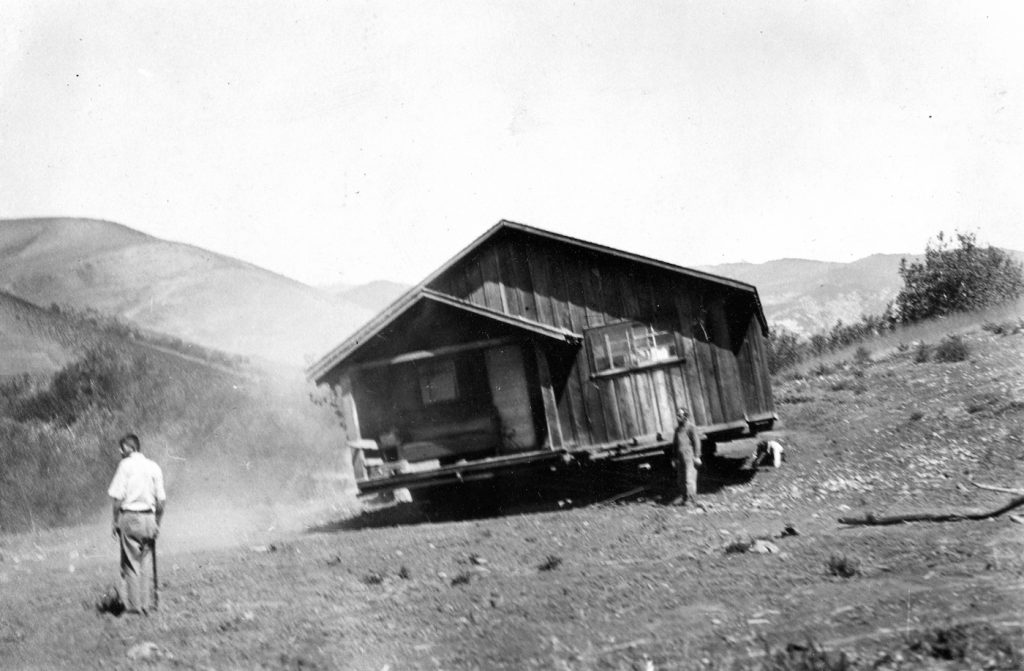

For the first time, the lands of Tajiguas saw significant change as modern water systems and electric generators were put in place. The hodgepodge of ranch buildings, dwellings, and sheds were moved to a central location to create a small-village down the road from the new hacienda.

In 1927, the Johnson’s purchased Mount St. George, the former John Murray Forbes estate in Montecito on Sycamore Canyon Road. They proceeded to tear down the matronly Victorian and hired George Washington Smith to design an Italian villa, which they called La Toscana. Though the Johnsons also spent time at their home in Beverly Hills and their apartment at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, they became intimately involved in the social and philanthropic life of Santa Barbara. Besides joining several clubs, they were involved with the Santa Barbara Foundation, the Music Academy of the West (of which Genevieve was a founder), and the Santa Barbara Historical Society [Museum]. Kirk helped organize the Memorial Cancer Foundation.

In the 1930s, Los Rancheros Visitadores signed a 49-year lease with the Johnsons for a permanent camp on the site of Rancho Tajiguas. By the time A.B. Ruddock purchased the ranch in 1954, it consisted of 3,600 acres with 80 acres of orange, 63 acres of walnut, and seven acres of avocado trees. There were five acres of irrigated pasture, 225 acres of grain, and the remaining acreage was grazing land.

And, as the McCarthy Era sped its way toward the Age of Aquarius, the sun stood poised to rise, however briefly, on a whole new era for Tajiguas.

(Sources: contemporary newspaper articles; ancestry.com; maps; histories of Santa Barbara County: Thompson and West and Yda Addis Storke; articles by Stella Haverland Rouse, Santa Barbara County Minute books; Jim Norris files at Santa Barbara Historical Museum.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.