Early Years of Rancho Tajiguas

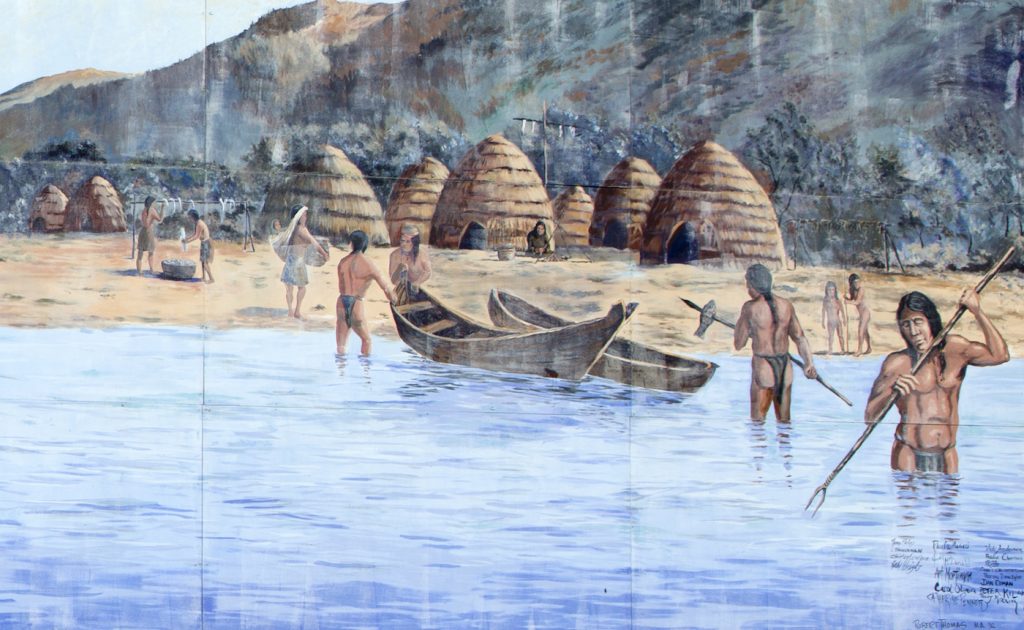

Lying among the rolling hills and fresh arroyos of the Gaviota coast, Rancho Tajiguas has been a favored spot for times immemorial. The 1769 Portola expedition, which prepared the way for Spanish settlement of Alta California, camped for the night at its mouth and were welcomed and entertained by the Chumash peoples living in two villages on either side of its river. Not knowing the Chumash name for the village, the Spanish named it Rancheria San Guido de Cortona., and made their way northward to found a mission near Monterey Bay.

Tajiguas Canyon had always been popular with the native Chumash, who gathered the holly-leaved cherry known as islay or tayiyas in September. It is believed that the name of the canyon is derived from the Chumash word, tayiyas, which may also have been the original name of the tribe. The fruit of the tayiya is sweet and edible, but it was the kernel inside the pit that was prized for grinding into a mash that was molded into cakes or balls and served with meat, such as baked gopher or squirrel. Of course, the kernel had first to be leached of its cyanide by running hot water through a bag of kernels or placing a basket of mash in running stream water. After that, it was considered to be quite tasty.

Old Spanish Days

In 1795, with 13 missions and 4 presidios and several pueblos established in California, the former commander of Santa Barbara’s presidio,CapitanJosé Francisco Ortega, obtained a Spanish provisional land grant of 26,529 acres along the Gaviota Coast. He named his lands Nuestra Señora del Refugio and they included vast acres of pasturage and 13 canyons of fresh water that drained into the Pacific. It was at Refugio Canyon that the Ortega family established their headquarters, near the Chumash village of Casil. As the Ortega family expanded, however, other canyons saw development.

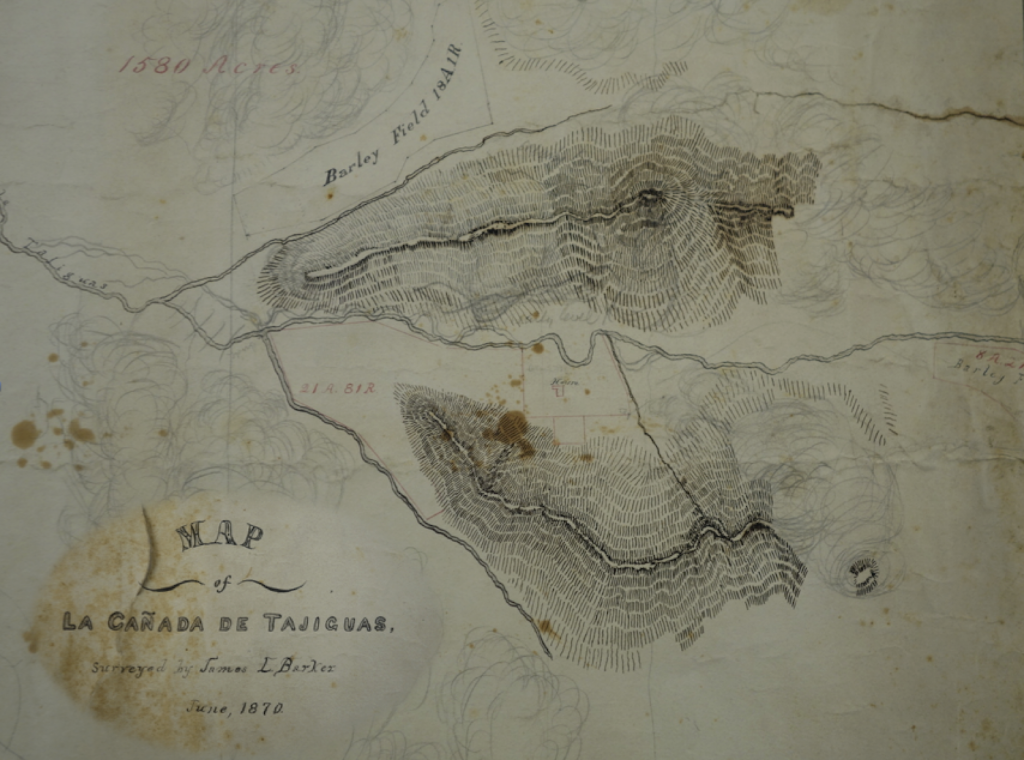

Tajiguas canyon was originally settled by El Capitan’s son, José Antonio Maria Ortega, who built a simple one-room adobe with two-foot thick walls circa 1800. By 1827, he was able to boast that vineyards and olive and fruit trees grew on the gentle slopes of the canyon and that fields had been planted. In 1834, the Ortegas finally obtained clear title to their lands when the Mexican government gave them Nuestra Señora del Refugio as the first official Mexican Land Grant in Santa Barbara County.

In 1836, Daniel Hill and family moved into the Tajiguas adobe, which he enlarged and remodeled. Hill had been first mate of the Rover when, as legend has it, he jumped ship after laying eyes upon the beautiful Rafaela Ortega at Refugio Bay. She being underage, he established himself as a carpenter, merchant, stonemason, and general jack-of-all-trades until they could marry, which they did in 1826. By 1846, sensing that there would soon be a change in government in California, Hill applied for and received a grant from Governor Pio Pico for 4,426 acres of his own, which he named, appropriately enough, La Goleta (the schooner) for a ship he is believed to have built near today’s Goleta slough.

Yankee Farmers

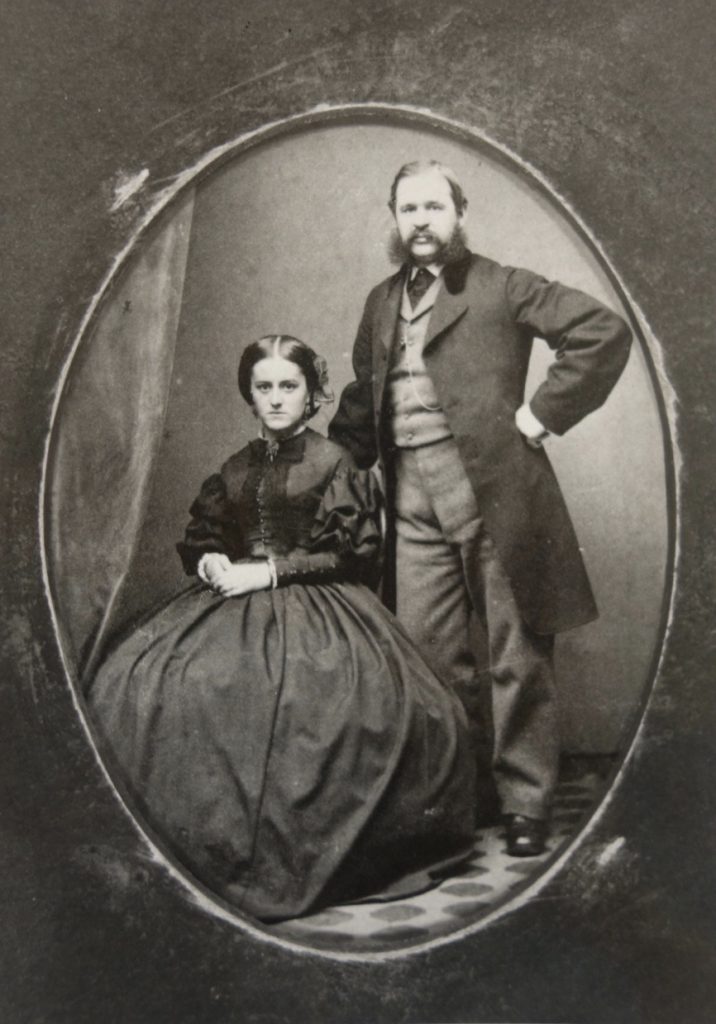

Though Nuestra Señora del Refugio was patented by the United States to the Ortega heirs in 1866, the family was not able to keep their rancho intact for long. In December 1869, the Tajiguas area was sold to Amasa L. Lincoln, a Massachusetts banker, and his friend, Frank C. Young. The Lincoln family and Young had come west seeking a healthier environment in which to live, Amasa’s eyes being a source of concern to him. After exploring San Francisco for land, they determined it was too expensive so they headed south. In a letter home, Abbie Lincoln wrote, “We start down the coast tomorrow for Santa Barbara… there to deposit me and the children in some boarding house while Frank and Macie [Amasa] buy them each a horse and scour the county for Ranches.”

As the men made forays into the countryside, Abbie explored the town and found it favorable. While they were gone she debated between buying a house lot in town or investing her bank money in a camels hair shawl. On the evening of the 21st of December, she was able to write, “Macie and Frank bought the property today that I mentioned. I think they were very lucky from all accounts, but I will not brag yet. There is hard work to be done!”

There was hard work ahead, indeed. A caravan of two wagons loaded with furniture, including a piano, negotiated the rough road to Tajiguas. Besides Amasa, Abbie, their two young sons (Lyman and Henry) and Frank C. Young, the procession also included Sam Ah, hired as cook, and a Yankee hired hand named Lance. Frank’s new puppy, extra horses, and a new colt completed the ensemble.

Abbie put on a brave face when she saw the old adobe. Noting that the house was situated in a little valley with a view of the ocean, she wrote, “To look at the old place, you would not think we could possibly be comfortable in it. But after all, the old adobe or mud house is the best suited to the climate. It is cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter than anything else. The roof is thatched with straw, three rooms have a floor, the rest have none. The kitchen is built at the end, separately.”

They set to work white washing the interior walls, tearing out the pigsties in the front yard and building a fence around the home so Abbie could plant some flowers. The fencing that did exist was made of chaparral. The property also had a barn, some vineyards and olive trees, as well as sheep, steers, cows, chickens, and horses. Guadalupe Ortega, shepherd and vintner, also lived there. All the hired help slept in the rafters of the adobe along with the stores of hay. Another shepherd, who may have been a native Chumash, was notable for wearing a blue army overcoat and commanding his charges from horseback while directing two splendid sheepdogs, one of which Don Pacifico Ortega had given them.

Don Pacifico came back one day to count the sheep by corralling them and having them jump through a hole in the fence to count them and present the accounting, for which he was owed recompense, to Amasa and Frank. He also presented Abbie with a housewarming gift of fifteen hens and a rooster. One hen was so tame she went inside to present her eggs on Abbie’s bed each morning. Abbie found this a bit too familiar.

Later in the year, Frank’s brother, George W. Young, joined them. Also later that year, Abbie made up her mind about her “bank money” and abandoned the camels hair shawl in favor of a lot on the northeast corner of De la Vina and Sola streets.

Life was hard on the ranch and that year’s drought took the spunk out of the banker turned farmer, so the family sold their share in the ranch to Frank and his brother George, and moved back to town during the summer of 1871. Their new idea for earning a living was to open a hotel. On Abbie’s lot a hostelry known as the Lincoln House (today’s Upham Hotel) was built. Amasa, however, didn’t stay employed as a genteel innkeeper for long because he was invited to take the position of head cashier for Mortimore Cook’s new bank.

That left Frank and George Young as sole owners of the Tajiguas Rancho. During their tenure, 16 acres of almond trees were planted near the vineyard that surrounded the adobe. This orchard was systematically harvested each year by ground squirrels. A quarter mile above the house stood a two-acre lemon grove. Above this, where the lateral canyons joined up, was a field of six or seven acres and another of 18 acres at the mouth of Lion’s canyon. They also raised dairy cows, which they took to San Miquelito Canyon for pasturage during dry summers.

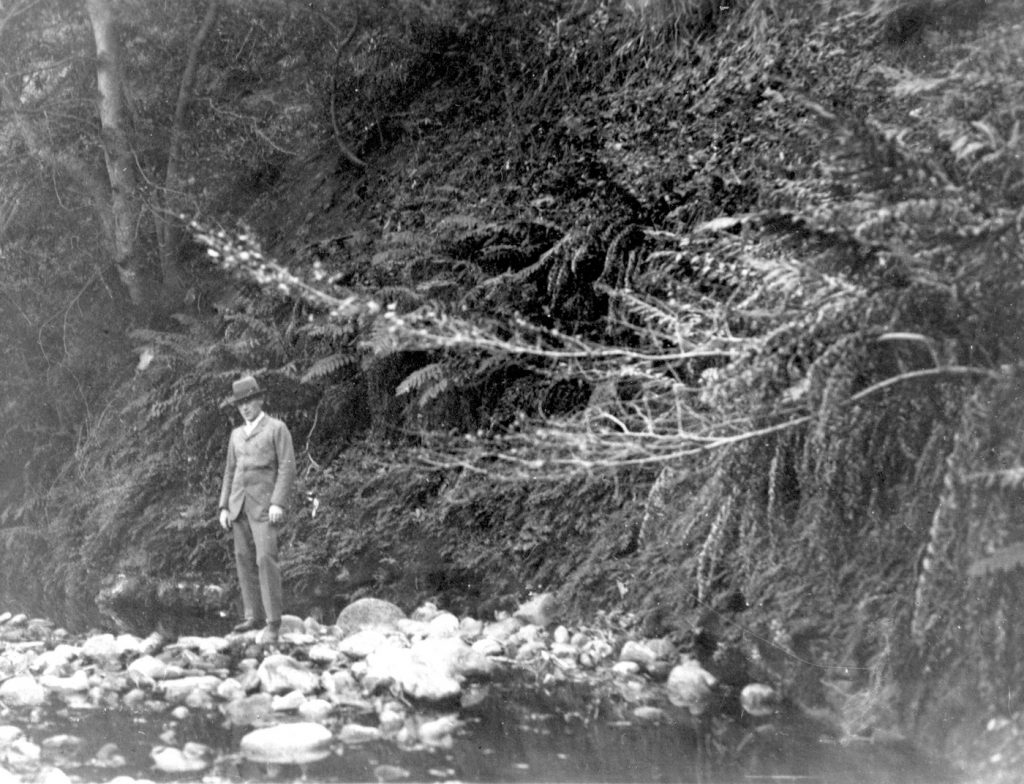

Botanists found Tajiguas canyon to be a sort of wonderland. One party made an excursion into the canyon to study a new subspecies of fern discovered by Elwood Cooper’s wife Sara. In horticultural speak it was named Chelilanthes cooperae and brought a certain fame to the canyon. (The Coopers cultivated olive and eucalyptus trees, among other crops, on their Goleta ranch. Both can be seen today by walking the trails of the Sperling Preserve at Elwood Mesa.)

By 1884, the ranch, which had been leased to Louis Cass Hill for his sheep and wool business, was for sale. In February, Lawrence W. More of the locally powerful and well-known More family bought the ranch and infused it with a new energy. (Continued next time.)

(Sources: Diary of Father Crespi as published by Father Palou; Jim Norris archives at Santa Barbara Historical Museum; “Use of Wild Cherry Pits as food by the Californian Indian” by Jan Timbrook; Mission Santa Barbara by Maynard Geiger; Noticias, “Rancho Tajiguas” by Stewart Ambercrombie; ancestry.com; Letters of Abbie Lincoln; contemporary newspaper articles.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.