On the Road with Arlo

The Atchison family came to Santa Barbara from Centralia, Washington, in 1912 seeking health for the father who suffered from chronic stomach problems. Alas, salubrious Santa Barbara was not able to work its magic on Garrett, and he died that July. His wife Sarah had set up housekeeping in a home on Carrillo Street, and her three sons quickly found employment. Arlo and his brother Garret Jr. soon opened an auto repair business at 418 State Street called Atchison Brothers, and Arlo’s twin, Otto, went to work as a clerk at Sterling Drug Company. After service with the 54th Heavy Artillery in France during WWI, Arlo returned to Santa Barbara to work at Central Garage, the local Buick Agency. Expertly trained by the Army Transport Service and a definite prodigy, he became shop foreman in 1921.

Today, long time classic car enthusiasts remember Arlo Atchison as the owner of the Horseless Carriage Restoration Shop. Before his cars became antiques, however, Arlo had been a superb mechanic for the most modern of automobiles of the 1910s and ‘20s. The working parts of the automobile were not his only passion, however, since Arlo loved going fast and owned and built racecars and speedboats as well. In the 1930s he became an airplane pilot so he could race through the skies.

Local antique car buff, Bob Burtness, says Arlo was an “ace fabricator,” who once made an antique clutch throw out bearing for Bob’s 1923 Hupmobile using a lathe and a block of steel. “He charged $13.50 to make it,” said Bob. “His work was always reasonably priced and he was a top ranked engineer repairer.”

Arlo’s expertise in all things “automobile” was demonstrated early on. When he was only 16 years old he built a Corliss engine. In 1924, at age 33, he received a patent for his invention of an electric windshield wiper.

Two and a half years ago, the Santa Barbara Historical Museum received a gift of a photo album from a descendent of the Atchison family in Montana. In it are photos of Arlo and his travels with his cars, just the ticket for a road trip to Santa Barbara’s past.

The Buick Redbird Racecar

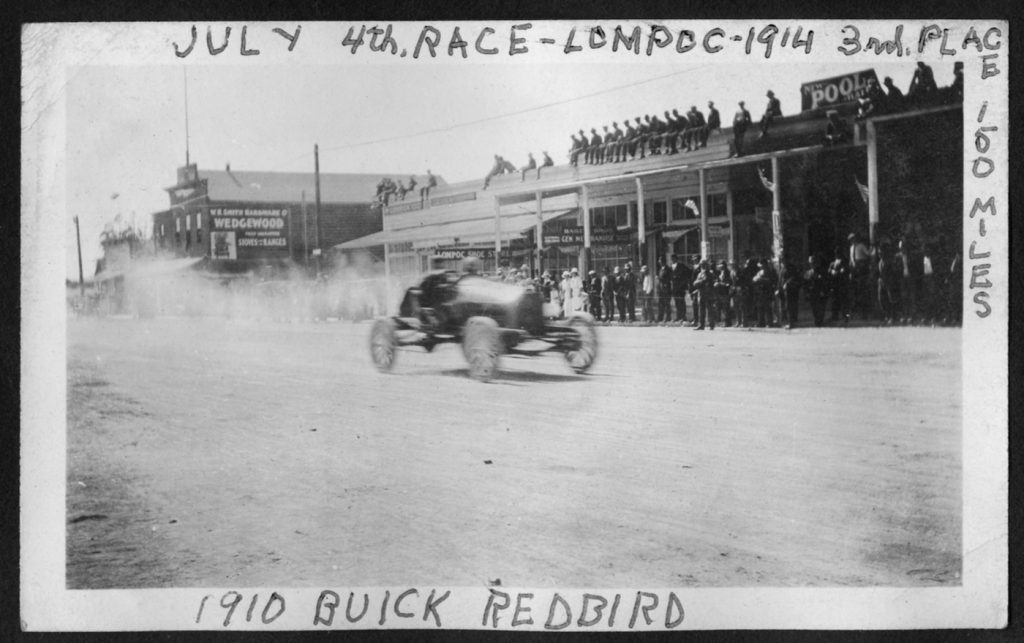

By 1915, Arlo had gotten his hands on a 1910 Buick Redbird roadster and turned it into a racecar before entering the 101-mile Fourth of July Race in Lompoc in 1916. The annual event had begun in 1912 when a group of businessmen in Lompoc initiated the road races as a feature of an expanded 4th of July celebration for the town. Events leading up to this main event included a decorated automobile parade, bronco riding contest, baseball game, foot races, a variety of horse races, bicycle races, and motorcycle races.

“At a quarter to three on Monday afternoon, July 3, 1916,” wrote David Cole in a 1987 article for the Lompoc Legacy, “eleven of the speediest light cars on the coast were lined up on Ocean Avenue of H Street ready to start Lompoc’s 5th Annual Road Race.”

The cars needed good brakes and good handling to negotiate the sharp turns and dirt streets of the 33 laps through town. They also needed to be able to accelerate quickly to a speed of 70 miles per hour on the straightaways to be in contention.

On the 24th lap, Arlo’s bright red Buick stopped at the pit where he found that every spoke in his right rear wheel was splintered. He was in 4th place and a contender for the money, however, so he decided to press on. Arlo maintained 4th place for a purse of $100, which translates as $2,400 in 2018 dollars.

Arlo loved that car and posed it at scenic spots along the roads for photographs. He must have enjoyed driving it on the 1912 Rincon Causeway, the new coastal road that connected Santa Barbara to Ventura. This road, essentially three wooden sections suspended horizontally from the cliffs, saved drivers a tortuous and steep climb up Casitas Pass that also added an extra 9 miles to the trip to Ventura. Before the causeway, drivers had to watch the tides to make sure they could drive on the sands to get around certain points on the route.

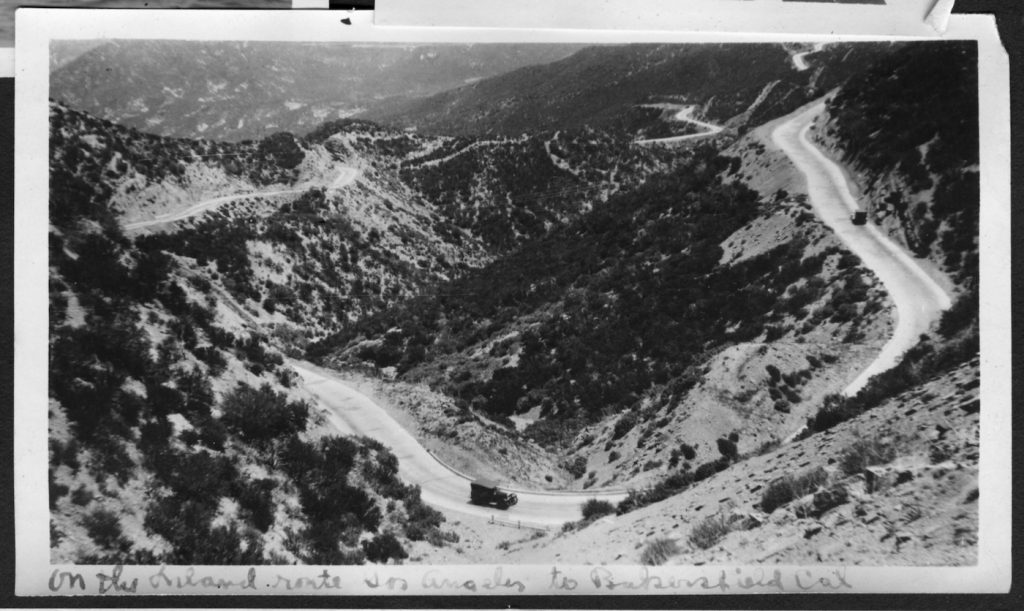

The Ridge Route

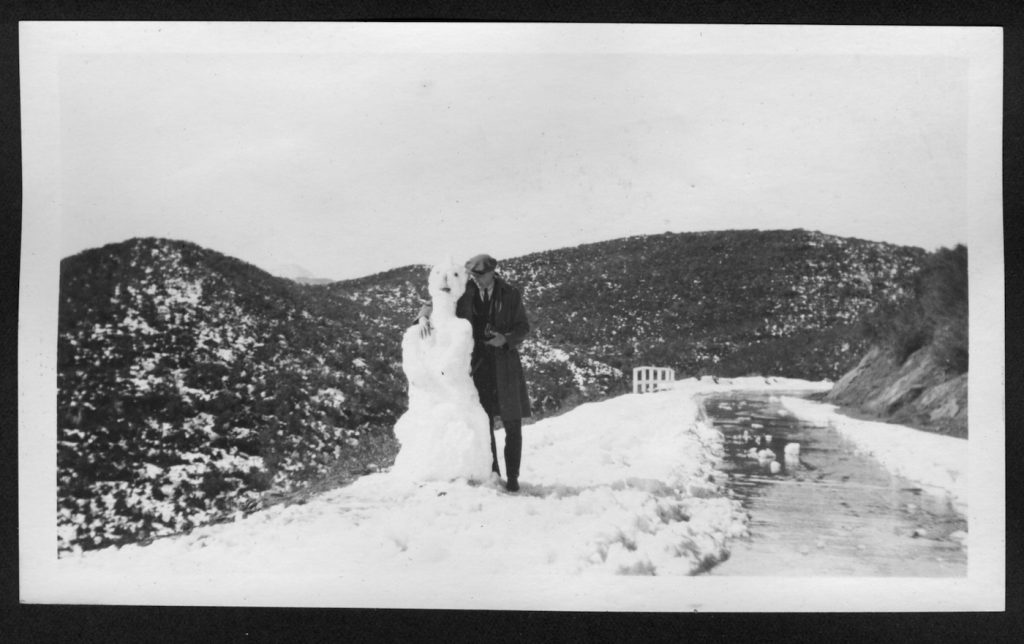

By 1921, Arlo had ditched the Red Bird and taken up with a more sedate Buick roadster on a snowy winter’s traverse of the 1915 Ridge Route that crossed the Tehachapi Mountains from Los Angeles to Bakersfield. Built by the State of California to facilitate travel between Los Angeles and the San Joaquin Valley, the road wound around the mountain peaks and wasn’t paved until 1917. It included several famous bends, like Horse Shoe Bend and Deadman’s Curve which became popular postcard views.

Numerous businesses grew up along the route and Arlo and traveling companion (possibly brother Otto) stopped at several. Just south of Horseshoe Bend, the Liebre Highway Maintenance Camp housed the equipment and men who were needed to maintain the highway. Besides numerous metal sheds, there was a small house of corrugated tin and wallboard for the foreman and a bunkhouse for the crew.

Arlo may have spent the night at the National Forest Inn, a white clapboard complex with nine heated cottages, most with running water, and costing $1-$2 per night. Though one could camp for 50 cents a night, with snow blanketing the ground, it’s unlikely there were any takers during Arlo’s trip. The Inn also maintained a garage and filling station as well as a dining room offering home cooked meals and lunches. Lunch cost 75 cents, and travelers could stock up on candy, tobacco, and postcards as well.

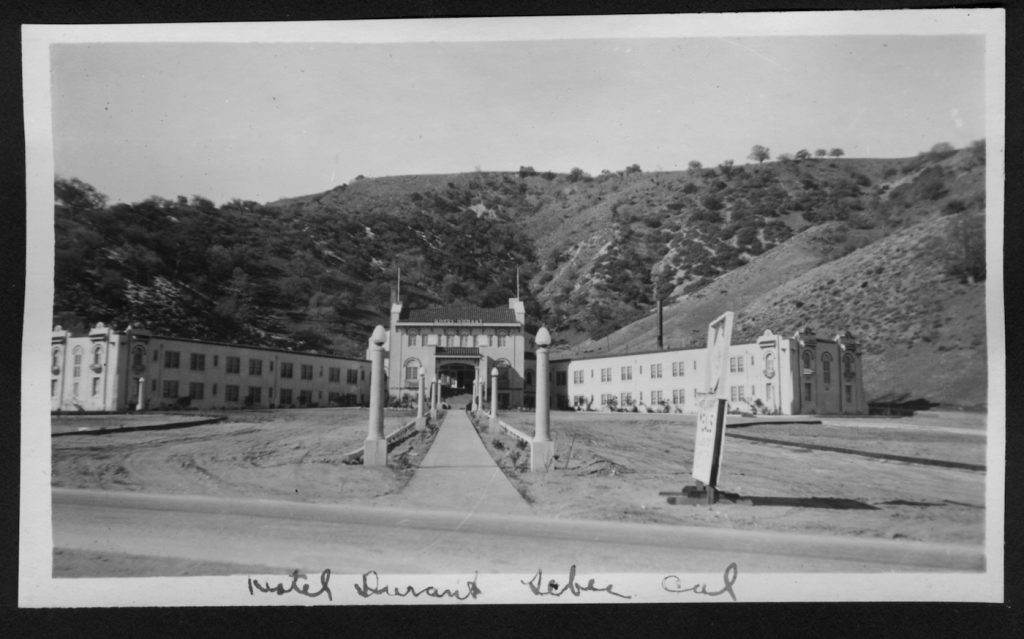

Arlo probably didn’t stay at the Hotel Durant, later known as Hotel Lebec, which had just opened in May 1921. The hotel was the creation of a saloonkeeper from Bakersfield, Thomas O’Brien, and the founder of General Motors’ playboy son, Russell Clifford Durant. In 1913 O’Brien had created a resort compound in Lebec, but at Durant’s urging and with Daddy Durant’s financing, the two partnered up in 1920 to create a first class elegant hotel on the Ridge Route. Each of the two wings carried 30 suites of two rooms with private bath. The luxurious dining room seated 400 guests and the hotel offered every modern convenience, a billiard room and views of Lake Castac (later renamed Lake Tejon). A double room with bath cost $4. The hotel quickly became the darling of Hollywood celebrities, and luminaries like Jack Demsey, Buster Keaton, Charles Lindbergh, and Clara Bow signed the register.

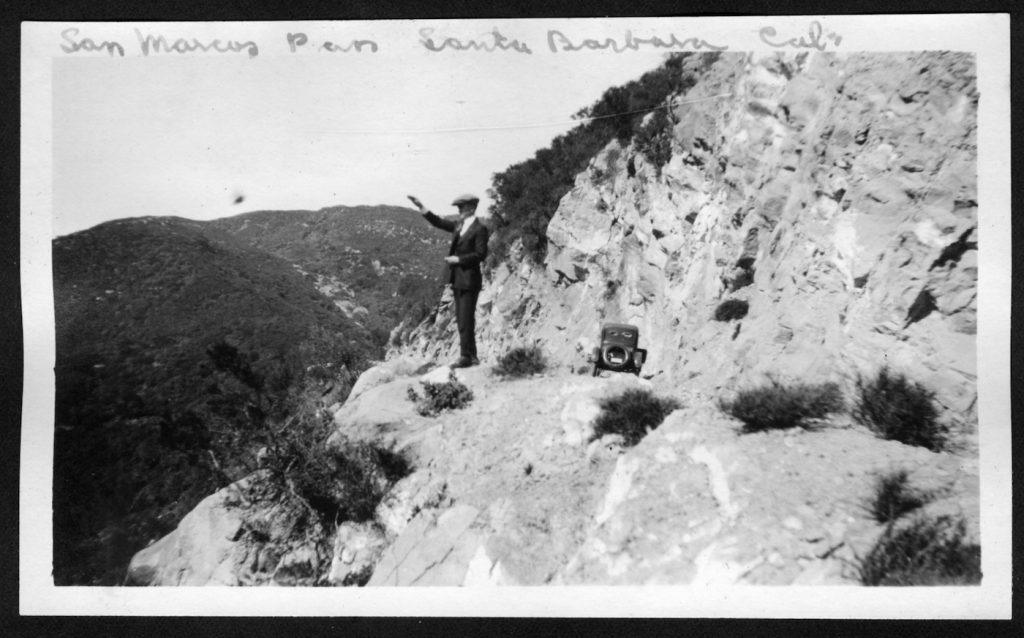

San Marcos Pass

Locally, Arlo tried out his new Buick on San Marcos Pass (today’s Old San Marcos Road). In the 1920s, San Marcos Road was still a twisting dirt road subject to washouts and rock slides. Local calls for its improvement went unheeded so several Santa Barbara philanthropists stepped in to pay for the work themselves. George Owen Knapp, Clarence Black, and David Gray all had mountain lodges that they wished to visit, so the road was kept in decent repair.

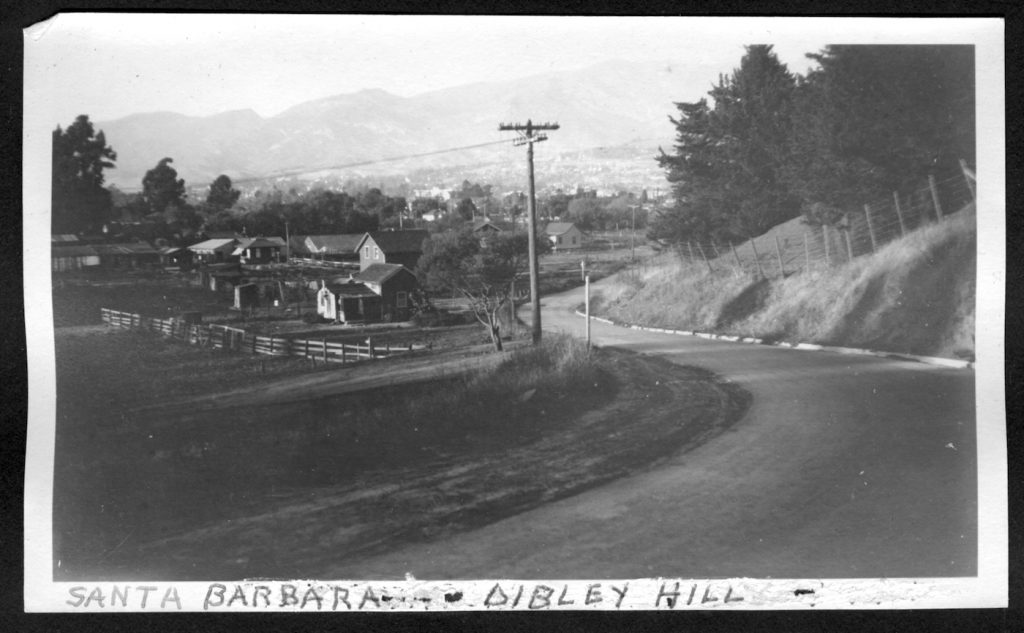

Old San Marcos Road had become the second stagecoach route and the main road over the mountains starting in the 1887. (The first route, completed in 1869, began at the end of Kellogg Avenue and crossed an escarpment called Slippery Rock.) Originally built as a toll road, all traffic had to stop at Summit House where station agent Patrick Kinevan supervised the change of horses and collected tolls. Kinevan also had a 160-acre homestead at the station and his wife Nora prepared meals for travelers at Summit House. The stage stopped running in 1901 when the Southern Pacific Railroad completed its line through Santa Barbara, but Summit House remained open. In the 1920s, Arlo, or perhaps his twin brother Otto, photographed one of his visits to the summit of San Marcos Pass.

Albums of photos, like the one donated by a member of the Atchison family, can provide important historical evidence of events and lifestyles of the past, which leads to an appreciation of our present. Besides, the images show so much more than mere words can relate and are completely fascinating. The Santa Barbara Historical Museum is fortunate that this family chose to preserve these images by donating them to posterity.

(Sources: “Lompoc Road Racing: Parts I & II” by David Cole, Lompoc Legacy No. 52 and 53, Winter and Spring 1987; Ridge Route: The Road that United California by Harrison Irving Scott, 2002; contemporary newspaper reports; ancestry.com sources; obits and cemetery records; Michael Redmon, “History 101,” Santa Barbara Independent, 13 April 2006.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.