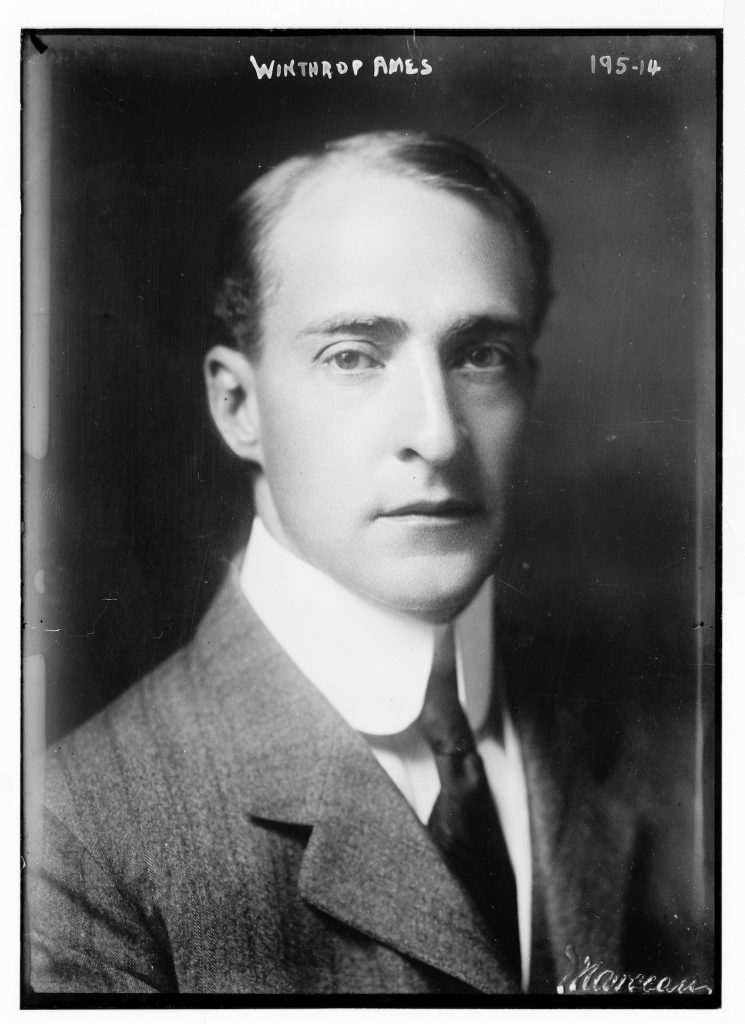

Winthrop Ames, Santa Barbara’s Community Arts, and Fiesta

Renowned New York theater producer Winthrop Ames (1870-1937) significantly influenced the development of Santa Barbara’s community arts programs, the opening of the new Lobero Theatre, and, by extension, Old Spanish Days Fiesta. Ames was born into a prominent family in Easton, Massachusetts, whose wealth derived initially from the manufacture of shovels and expanded exponentially through investments in ironworks, railroads, mining, and other ventures. Rather than go into the family businesses, however, Winthrop attended Harvard University and studied art and architecture.

After the turn of the 20th century, Ames became interested in theater management and went abroad to study the drama and theaters of Europe. When he returned to New York in 1908, he became the managing director of New Theatre, where he intended to establish repertory companies that could produce cutting-edge plays free from the pressure of financial profitability. Despite Ames’s patronage, the elaborate theater was not a success and closed a scant two years later.

In 1912, Ames used his own money to build the Little, a 300-seat theater located at 240 W. 44th Street. The idea was to put on experimental dramas and give opportunities to new playwrights. As such, he became part of the Little Theater Movement popular at the time in the more esoteric circles of American theater where experimentation and the search for new dramatic expression were paramount.

Long mentioned in local newspaper articles regarding his work in New York, Ames was mentioned for a different reason on December 12, 1919, when the Morning Press reported, “Winthrop Ames, who has been managing the Little theatre in New York, where so many interesting plays have been produced, and Mrs. Ames will spend this winter in Santa Barbara. They have taken Glendessary, Mrs. Robert Cameron Roger’s [Beatrice Fernald] delightful house in Mission Canyon for three months, and will arrive the first of the year.”

In March, Hobart Chatfield-Taylor, a noted author and strong supporter of local cultural programs, gave a small luncheon at Far Afield, his home on Hot Springs Road in Montecito for the Ameses. Included among the guests were Wallace Rice, the author of an upcoming extravaganza production, La Primavera, andVictor Mapes, New York playwright, stage manager, and director, whose play “Boomerang” played on Broadway in 1915-16. A frequent visitor to Santa Barbara who lived part-time in Montecito in his early 20s, Mapes debuted his play, The Lame Duck, on the Potter Theatre stage in January 1921.

With all this talent in town, there was certainly no dearth of thespian society in Santa Barbara in the years following WWI.

The Road to La Primavera

After a pleasant 1919/20 winter season, Ames and his wife were prepared to leave for New York on March 1, but they were persuaded to stay until after the inaugural La Primavera festivities. La Primavera had come about after the success of a five-day multi-faceted and extravagant Fourth of July celebration in 1919. In May 1919, just six months after the end of WWI, the Commercial Club of Santa Barbara planned a festival that they hoped would, as the Morning Press reported, “reinvigorate the historic and romantic Spanish past.” They also hoped it would reinvigorate the diminished coffers of Santa Barbara’s business community.

Many, however, wanted the annual fiesta to be solely on behalf of the survivors of the pioneer Spanish families of California and their descendents. E.H. Sawyer, pioneer Montecitan and former owner of the Hot Springs Resort, said, “We owe the past a big debt of gratitude, and our Spanish heritage is one that must not be permitted to fade into forgetfulness…. Our younger generation needs to be reminded of what has gone before. The past is sacred. If we can make Santa Barbara the annual rallying place for the descendants of the pioneers and reverence their memoires in song, story, and pageants, we will be engaged in a truly worthy work.”

The five-day Fourth of July celebration featured three parades and was dubbed Fiesta Week. The first parade on July 2 was a costumed Spanish pageant that featured silver saddles and caballeros on horseback as well as romantic couples riding tandem. To further the Spanish theme, ramadas and casas were built along Plaza del Mar for the old Spanish marketplace. Old Spanish songs were sung and old Spanish games played. The second parade was a historic pageant of Santa Barbara, and the third honored the men and women who had served in WWI and all previous wars.

“The fiesta closed at midnight last night in a blaze of glory,” reported the Morning Press on July 6. Encouraged by the popularity and financial success of the celebration, plans went forward to make it an annual affair. By September, a committee led by James Rickard and composed mostly of businessmen such as grocer John Diehl, attorney Francis Price, and druggist A. M. Ruiz was joined by philanthropists and civic promoters Dr. C.C. Park, Clarence Black, and Charles L. Taylor, an officer of the Carnegie Corporation. Celebrating Santa Barbara’s Spanish heritage in an annual festival, they believed, would draw thousands of visitors to Santa Barbara and support local businesses.

In so doing, they drew not just upon the recent successful Old Spanish Days parade, but also the annual Floral Festivals, which had flourished from 1892 through 1896. These annual spring festivals sought to promote Santa Barbara County agriculture through expositions of horticultural products at the Agricultural Pavilion and fairgrounds, which lay north of today’s East Cabrillo Boulevard. Spanish culture was represented during Festival Week 1892 exhibitions of Mexican and Spanish horsemanship. The last Floral Festival was held in 1896, after which civic promoters decided that the expenses of the festival did not warrant the results and the event was discontinued.

La Primavera was also to be held in springtime, but its focus on solely celebrating Spanish culture hearkened back to the celebration held in December 1886 for the Mission Centennial. Organized by the Go Ahead Club, the festivities intended to raise money for a new roof for the Mission. For the parade, a cypress and palm frond replica of the Mission created an arch over State Street, and merchants bedecked their buildings with banners, flags, and bunting. Most of the entrants in the parade were dressed in Spanish attire and reflected Santa Barbara’s early years, with the notable exception of a donkey cart driven by Santa Claus. A Spanish rodeo exhibited the old vaquero days of California, a display that became so brutal and bloody that a young boy sitting on the fence fainted. The agricultural displays were less sanguinary, and the final exhibition of Spanish dances at the old Lobero Theatre crowned the glorious celebration.

La Primavera

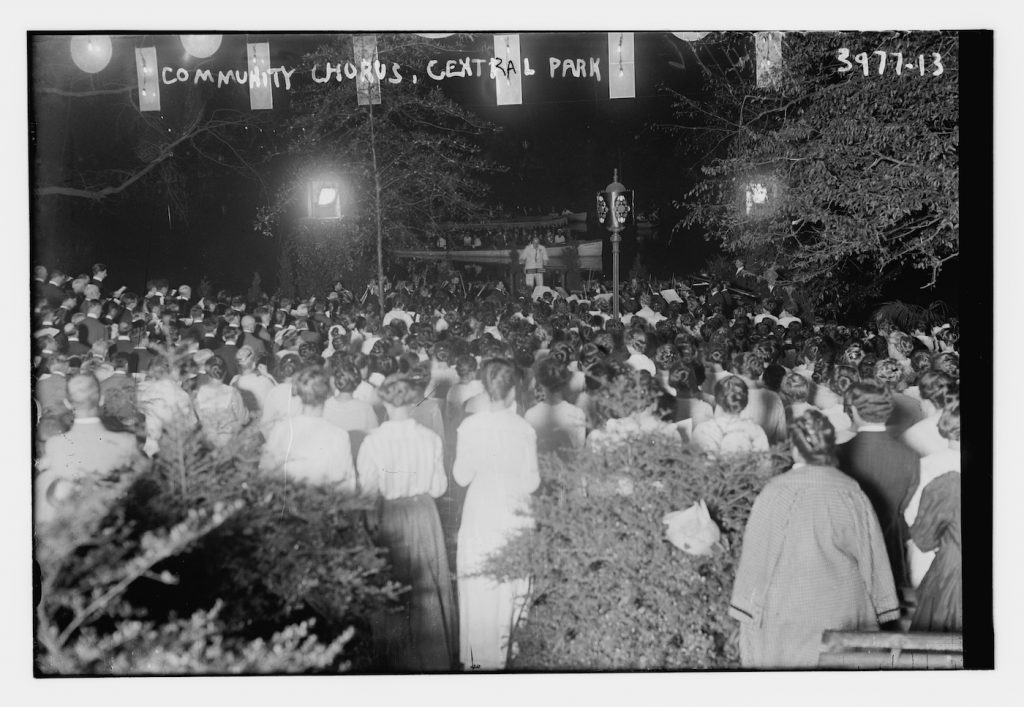

The organizers of La Primavera drew on these historic occasions plus the advent of the community arts movement in the early 20th century. This movement sought to involve the entire community in music, drama, and art in order to transcend the drudgery of the workaday world and elevate the human spirit. In September 1919, the first community-wide effort was instituted when Arthur Farwell came to town to organize a Community Chorus at the behest of Marion Craig Wentworth, noted playwright, poet, suffragist, and socialist who had recently moved to Santa Barbara. Farwell, along with Harry Barnhart, had started the national Community Chorus Program in 1913 in New York.

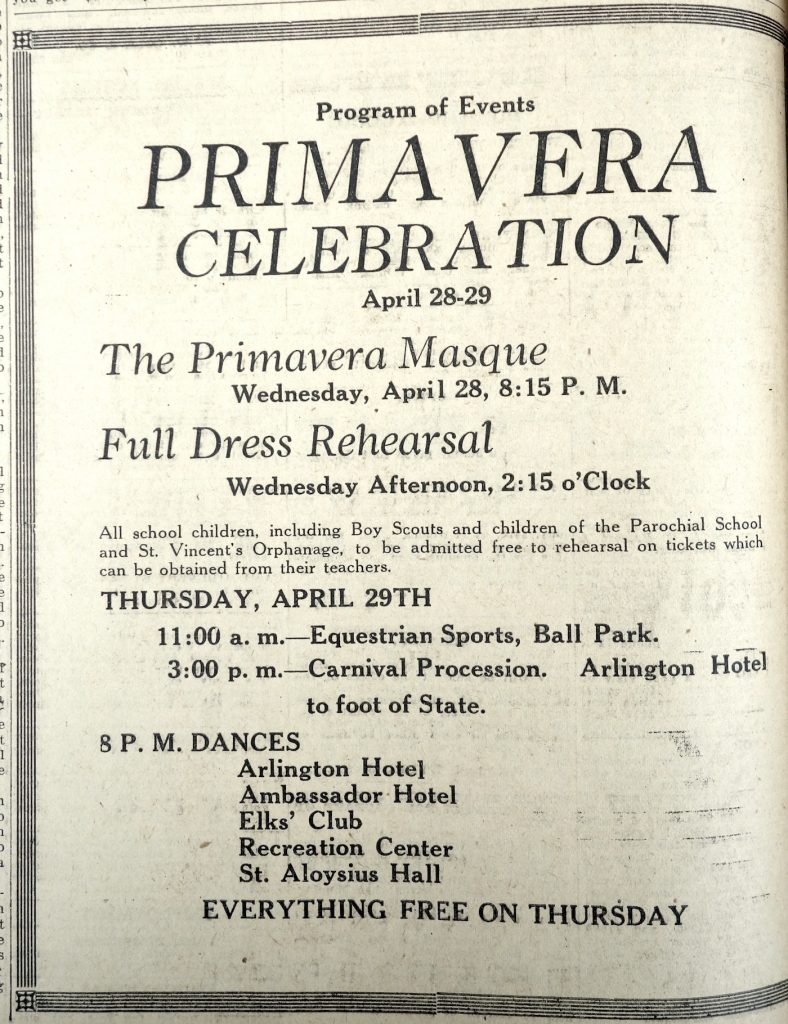

By January 1920, the Chamber of Commerce had hired a professional, Wallace Rice, to write the masque for an ambitious production of dance, acting, pantomime, music and song that celebrated Santa Barbara’s historic roots. They began soliciting guarantors for production expenses and recruiting and training participants. By April, the show was ready to go on. In addition to the Masque, La Primavera offered equestrian sports, a parade, and dances at all the principal places.

On April 28, 1920, a parade of horsemen dressed in Spanish colors leading more than 1,000 children, dressed in white and garlanded with long streamers made of fern leaves fastened together with bright flowers, marched down State Street to music furnished by several bands.

The Masque, written by Wallace Rice, and the production, directed by Samuel Hume, and the music, directed and organized by Arthur Farwell, was a resounding success. According to the Morning Press, the play was given “in the enchanting and romantic atmosphere of a natural theatre, which nestles among the foothills near the Neighborhood House.” (Neighborhood House, a social service organization, stood on the north side of De La Guerra Street just above Garden Street.)

The Morning Press review was glowing, calling it frolicsome and spirited in presenting a series of inviting pictures of what life was like years ago in Santa Barbara. The costumes were spectacular, the dances a whirlwind of color, and the music incredible. The performance, the reporter said, “was punctuated by pretty old Spanish melodies, which had all but died, and pretty, fresh young girls in the dances of those old and romantic days, and promises to become a healthy rival of the famous Mission Play at San Gabriel.”

When plans for La Primavera were ramping into high gear in March, the Morning Press reported that distinguished Eastern theater manager Winthrop Ames planned to prolong his visit in Santa Barbara to see the Primavera pageant-masque and festival. Ames even visited the Primavera headquarters in the adobe at 31 East de la Guerra Street and was taken to the pageant stage below Neighborhood House, uphill from Garden Street.

Ames was so interested in the effort to celebrate the city through a great stage spectacle that he volunteered his services in any capacity needed. When he saw the site of the stage (on the hillside above Garden Street between De la Guerra and Canon Perdido), he thought there was a great opportunity to build a theater there that would surpass the Greek theater at Berkeley.

“Nothing is better for a community,” Ames told the reporter, “than this sort of concerted effort to produce a community play on a stage. It not only brings together the large number of persons from all classes in the city required to give the necessary pageant effect, but it brings into even closer relation the practitioners of the finer arts.…. What is perhaps best of all, the entire city shares in the joy coming from artistic creation done in the spirit of gayety and play. It may well amount to recreation of a spirit that will thereafter yearn for something more than the every-day things of life, and be able to find expression of that spirit.”

Unfortunately, La Primavera was not a financial success, and though the organization stumbled along for a few more years, it never could launch such an elaborate event again. It was, however, the inspiration for the establishment of community arts, which became organized as the Community Arts Association Players in 1920 (Drama Branch), the Santa Barbara School of the Arts in 1920, the Community Arts String Orchestra in 1921 (Music Branch), and, eventually, the Lobero Theatre and Old Spanish Days Fiesta in 1924.

Community Arts

For the 1920-21 season, Winthrop Ames and his wife, Lucy, leased James Waldron Gillespie’s home, El Fureidîs, in Montecito. No other home could have been more appropriate than Gillespie’s dramatic estate of Persian water gardens, meandering paths, and lush plantings surrounding the Goodhue-designed home of eclectic Spanish design. The fact that the grounds had been used for numerous silent movies would not have gone unnoted by Ames.

During his time in Santa Barbara, Ames expressed great interest in the development of drama in Santa Barbara and was most impressed with the Community Arts Players and their director, Nina Moise. Being one of the earliest practitioners of the Little Theater movement in the United States, he was particularly interested in the work the new Santa Barbara School of the Arts was doing to further the movement. Under the direction of Marion Craig Wentworth, the School of the Arts had inaugurated a little workshop theater, where, reported the Morning Press, “all pupils of the school are given an opportunity to try out their ability and practice the delightful art of make-believe.”

During a performance of three one-act plays in the old Adobe home of the school, Ames was so impressed by the ability and stage presence of local high school student Muriel Starr that he offered to bring her east and place her on the legitimate stage after three more months of study with Marion Wentworth.

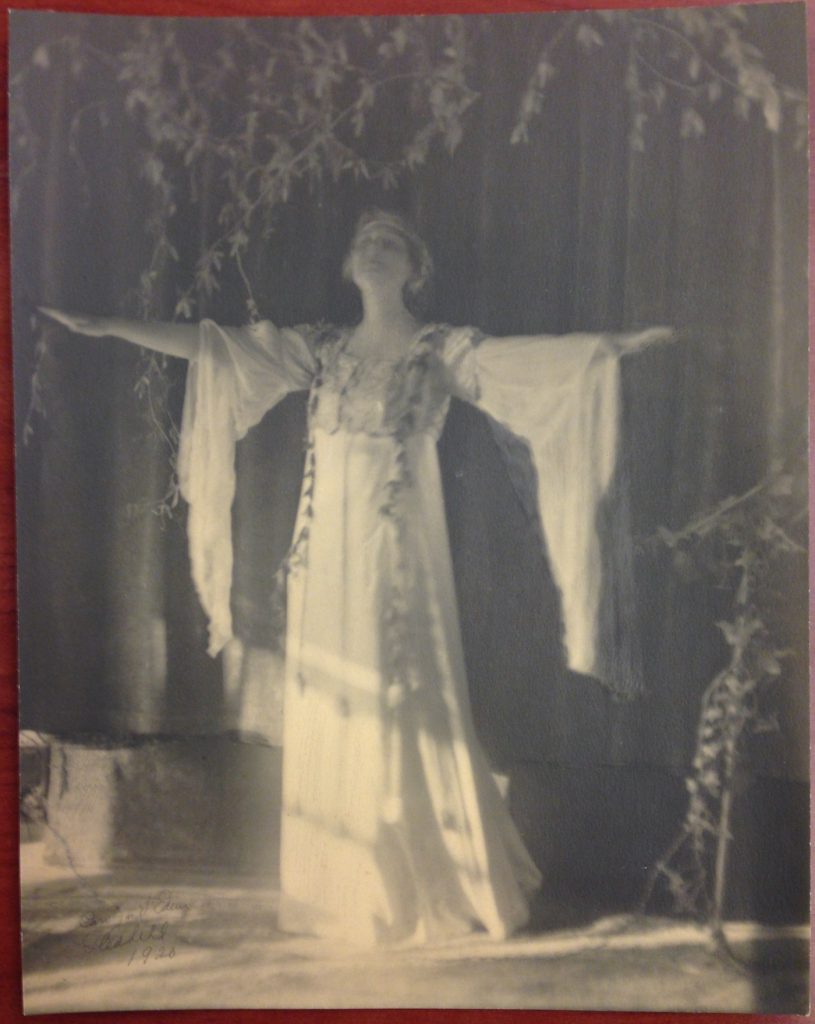

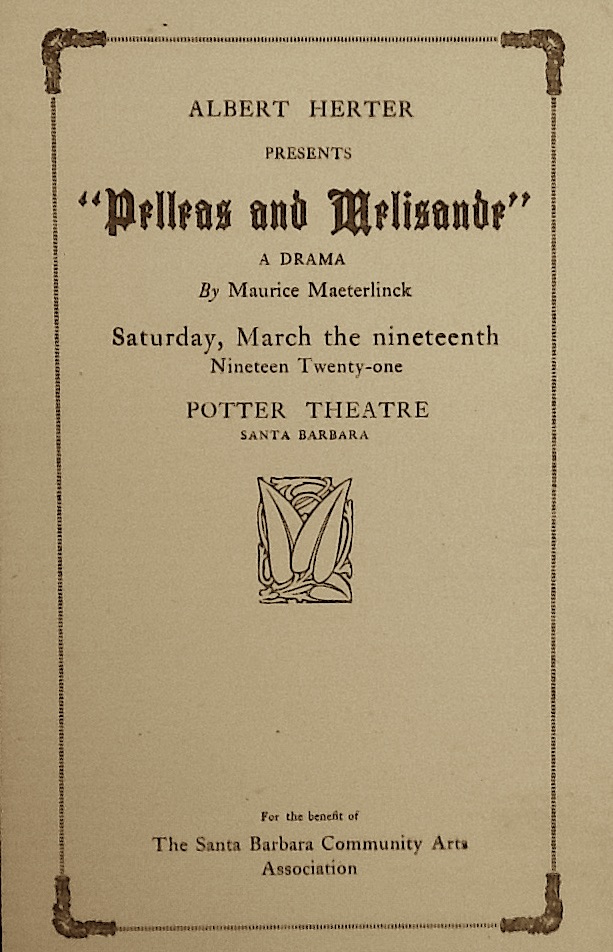

In March, Ames attended Albert Herter’s extravagant production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s Pelleas and Melisande, a benefit for the Community Arts Association given at the Potter Theatre. A richly woven tapestry of music, color, story and art, the play was reviewed by Sara Redington, who was overcome by the magic of the spectacle. She wrote that Pelleas and Melisande was “A dream by the flickering light of the dying fire that throws haunting shadows on the wall of the old castle room – until the figures in the tapestries wake, and stir – and come among us to whisper that they were once men and women, only they came from Fairyland – long, long ago.”

Ames, who was in the audience and was invited to the studio supper given by the Herters after the performance, wrote a letter saying, “Very rarely is a stage production anywhere designed and supervised by an artist of Mr. Albert Herter’s rank. Very seldom do amateurs so well convey the mood of a difficult and atmospheric piece as the Community Players have done under Miss Moise. Nor is Debussy’s intricate music often interpreted with more delicacy than by Mr. Clerbois’s orchestra. Altogether, the production of ‘Pelleas and Melisande’ seems to me a really notable achievement by the Community Arts of Santa Barbara.”

High praise, indeed, coming from a noted Broadway director whose influence and patronage of Santa Barbara theater would come to the forefront again in 1924 for events surrounding the opening of the new Lobero Theatre and the successful establishment of an annual fiesta for Santa Barbara. Santa Barbara was indeed fortunate to have had his support and patronage.

(Sources: Contemporary newspaper articles; Wikipedia; Ancestry.com resources, Santa Barbara City Directories; Library of Congress prints and photographs online; Oxford Reference online; playbills.)

You must be logged in to post a comment.