The Allosphere Science Meets Art

In an unprecedented frame, Nathan Vonk, owner of Sullivan Goss Gallery, accepted a proposal from Dr. JoAnn Kuchera-Morin, director and chief scientist of the AlloSphere Research Facility [UCSB] and her team including Dr. Andres Cabrera, Media Systems engineer; Dennis Adderton, technical director; and Gustavo Rincon, grad student, to present their latest work for free to the public at the gallery on April 28.

The effort they presented is a mini-representation of Kuchera-Morin’s AlloSphere at UCSB. The mysterious building, as Vonk stated, is the culmination of her 34 years of research in orchestral composition, creative computational systems, multi-modal media composition, and facilities design. It is a 30-foot diameter, 3-story high metal sphere inside an echo-free cube used for interactive scientific and artistic investigation of multi-dimensional data sets. Inside is a 10-meter diameter custom-built close-to-spherical screen, 26 immersive projectors, 14-computers rendering cluster, 54.1 channels of sound, with multi-user interactivity. Research is in the following four fields: Arts and Entertainment; Bio-technologies and Medical research; Physics and Quantum Mechanics; and Materials.

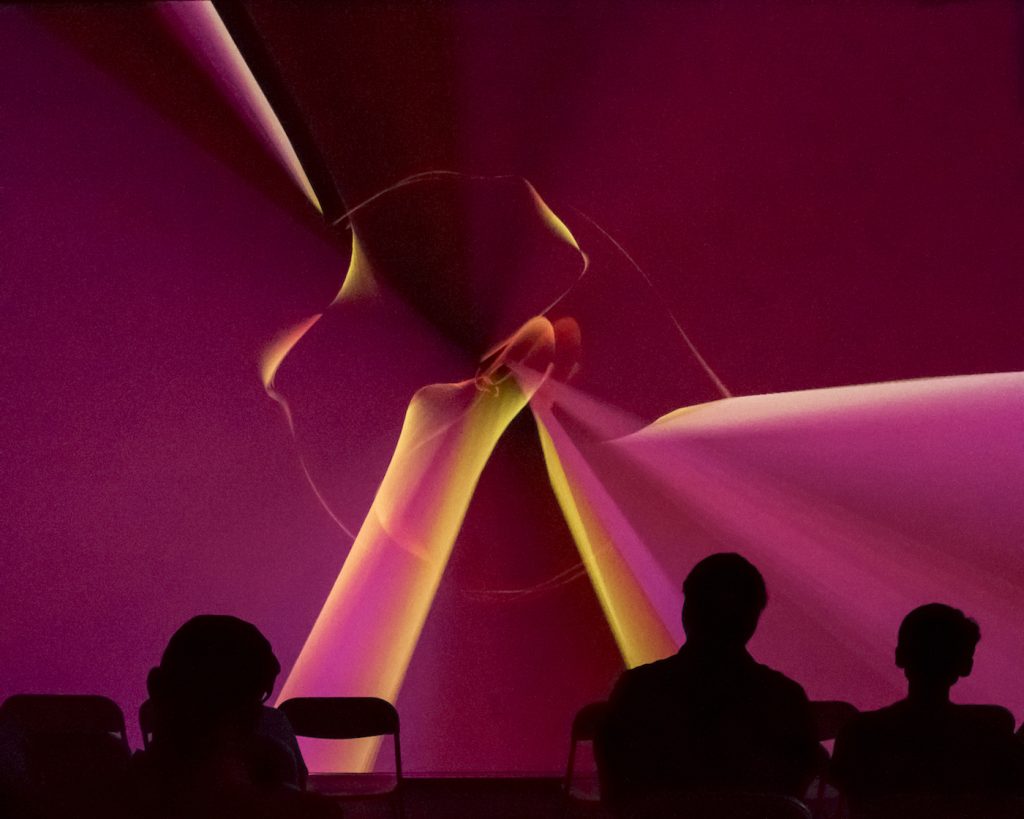

The presentation to a standing room only crowd at the gallery consisted of two movements of Kuchera-Morin’s science-sonata titled “Probability”, with reference to Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle in Position and Momentum for an Atom. Attendees wore 3-D glasses while viewing a projection on the gallery wall with stereo sound. The “art” was a simulation of the probability of where an electron may be, specifically the hydrogen electron and the flow of it. The video’s colors, shapes, and the tonal pitch used were chosen by the team “arbitrarily.” After the viewing, she fielded questions and further discussed the work being done in the field.

My review of the work is that while appreciated for its use to demonstrate physics equations via a computer software program that yields color waveforms and sound, we have for certain seen and heard this art genre from prominent video artists involved in conceptual art and experimental film for many years. Steina and Woody Vasulka used video synthesizers to create abstract works as noted in their film Violin Power in 1978, and lest we forget the first analog attempt at experimental visual waves in the silent film Anémic Cinéma [1926] by Marcel Duchamp, and the acoustical theory of sound as waves proved by 18th-century scientist and musician Ernst Chladni. While one appreciates the premise of the Allosphere’s design, the output shown at the gallery in art is rendered and is temperate to the seasoned creative, and noted as such among some of the attendees at the gallery presentation.

I interviewed JoAnn prior to the presentation to delve deeper:

Q. What prompted you to go from music composition to digital sound?

A. I have traditional music roots, with a Ph.D. in music composition from Eastman School of Music. To me, the arts use the principles of science. I thought, why not have art be used to demonstrate what scientists are writing, instead of just looking at their equations. Both disciplines use symmetry and asymmetry. Also, with the downturn of jobs in music, it was clear to me that the direction for music would be digital. I was working on the old Vax and PDP computers. The only company that made a digital to analog computers for sound was based in Santa Barbara, called Digital Sound Corporation. I wanted real-time digital sound output, so I purchased one of their computers and came to work at UCSB. I thought I was going to be in the music department, but when I arrived, they had placed me in engineering, as no one in music was using computers at the time. The department told me, “Why would anyone want a computer to make sound?!” Computers making music had already happened in the U.S. with Bell Telephone Labs engineer Max Mathews.

I continued to work in many other areas at UCSB, interfacing with physics, math, and material sciences. The AlloSphere is the result of all those years. [Montecito Journal notes: Jim McGill a Ph.D. physicist, founded Digital Sound Corporation at 2030 Alameda Padre Serra Santa Barbara in 1978, which specialized in microchips necessary to process data from electric musical instruments and microphones, and later branched out into voice-mail devices. Max Matthews got an I.B.M. 704 mainframe computer to generate 17 seconds of music titled “The Silver Scale” composed by Newman Guttman, his colleague at Bells Labs. Four years later, he programmed an IMB computer to play “Daisy Bell”, later noted as the inspiration for the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.]

What is your latest work we will view at the gallery?

For the past seven years, I worked with Luca Pelitti, Ph.D. [Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics & University College London], and Lance Putnam, Ph.D.on the computerized simulation, visualization and sonifcation of electron wave functions in a hydrogen-like atom. This simulates and displays the quantum mechanical wave function of a single electron in a superposition of different atomic orbitals using solutions of the time-dependent Schrödinger equation. The software program is set up in three versions: 1) a single wave function is visualized while agents follow fields of electron current and gradient; 2) agents form ribbons showing electron spin in an simulation that is the product of three separate wave functions; and 3) visualization uses isosurfaces to display the same simulation.

How does this presentation replicate the work at the AlloSphere?

For this gallery presentation, we reduced the AlloSphere down to one projector, one computer, and a two-channel sound system. We are now portable enough to bring the Allosphere to the public, so people can find out what we are doing there. Also, the software program written by my colleagues and students is publically available as an open-source software system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.